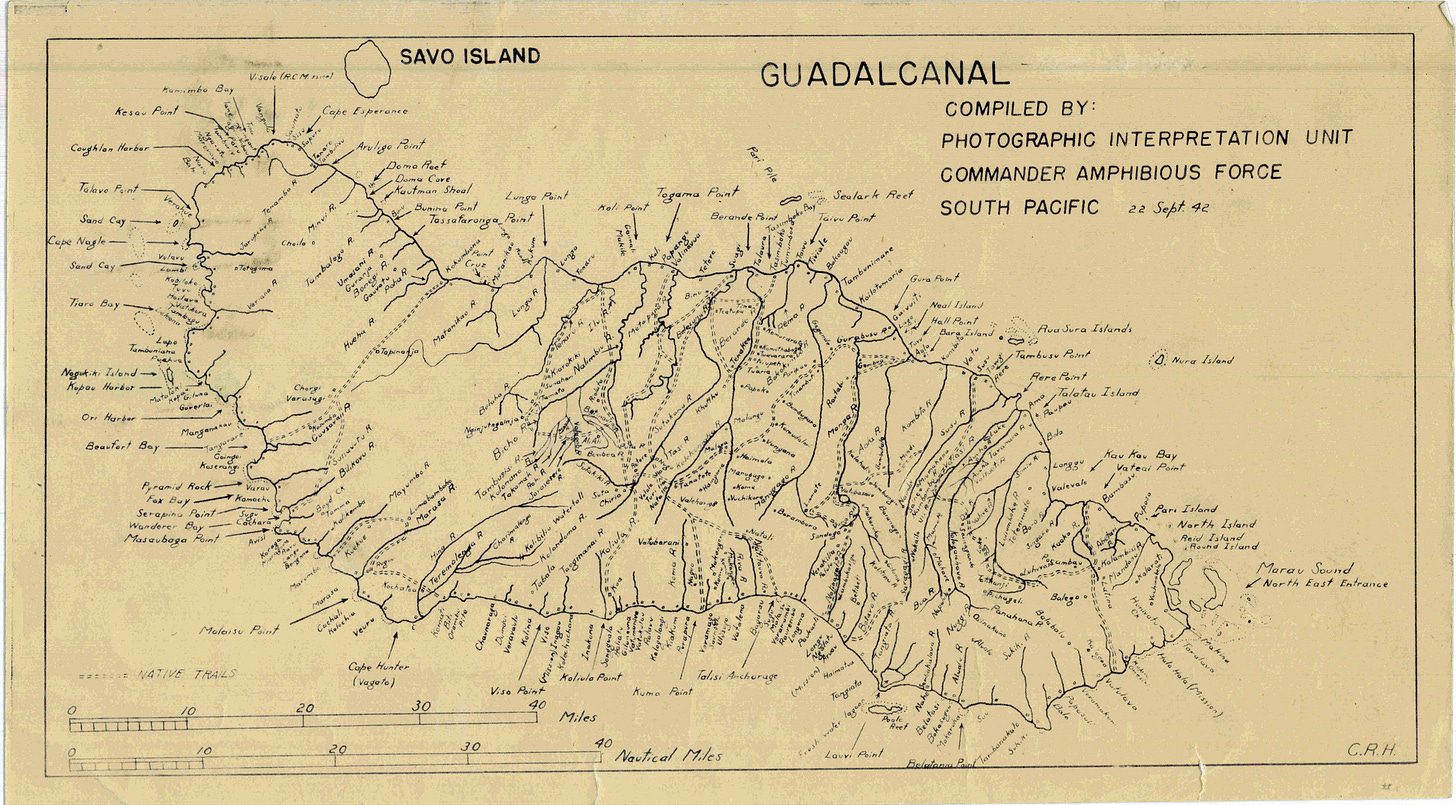

Operation Watchtower - Guadalcanal

Part 1 of a look back at a series of stories on the first land operations by US forces in the Pacific, and the accompanying battles at sea and in the air

The invasion of Guadalcanal1 by the US Marines in August 1942 broke some basic rules for amphibious warfare. The US did not have command of the seas around the Solomon Islands, and they did not prevail in the skies above.

There was a clear Allied policy of ‘Europe First’, fully supported by Roosevelt, intended to limit Pacific operations to holding operations only. But there was a growing recognition that it was necessary to make a stand somewhere - and halt Japanese expansion. The US Navy was led to the decision to intervene whether they were fully prepared or not.

That left the Marines on the ground to solve the problem as best they could. During the early days, they would call it ‘Operation Shoestring’’ with good cause. Offshore the US Navy began operations months ahead of the arrival of a stream of new carriers and ships that would have put them in a much stronger position. They took just some hard knocks as a consequence of moving early. After a bloody struggle of just over six months, both succeeded, with a series of battles on land and at sea giving a foretaste of how the Pacific war would develop.

The US Marines established themselves on Guadalcanal on 7th August and seized the airfield being built by the Japanese with little difficulty. But the Japanese Navy mounted a fierce counter-attack the following day - forcing the US Navy to withdraw from the area. The Marines on Guadalcanal were left without half their supplies and had to adapt rapidly to living in the jungle.

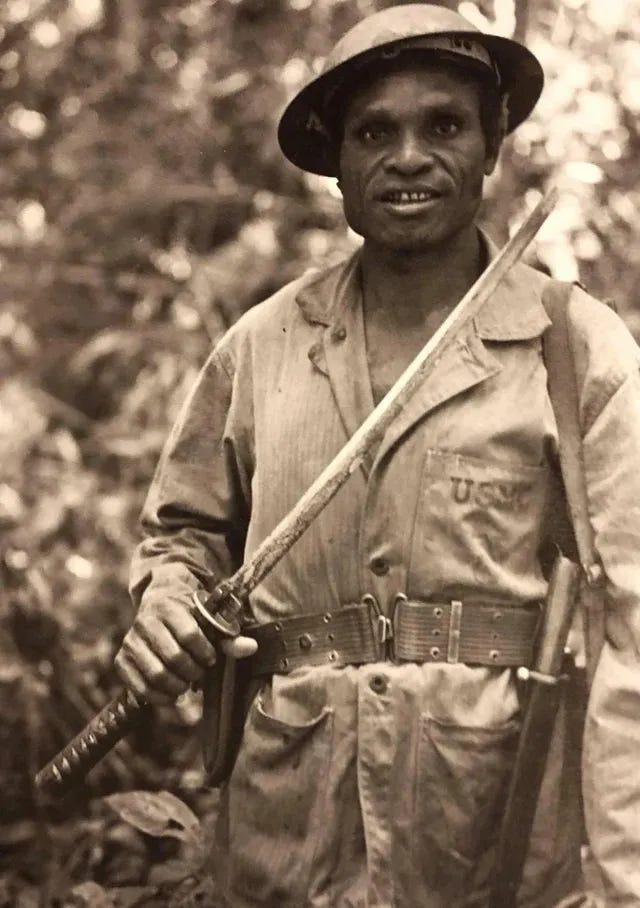

They were assisted by the native islanders of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force. Among them, Jacob Vouza was to distinguish himself.

A desperate attempt by the Japanese to make a frontal assault on the Marine lines saw them being annihilated, at the Battle of the Tenaru.

In the seas in and around the Solomon islands a series of naval battles took place including the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

Meanwhile, the airfield on Guadalcanal, now renamed Henderson Field, was under sustained attack from Japanese planes.

Almost daily, and almost always at the same time - noon, "Tojo Time"- the bombers came. There would be 18 to 24 of them, high in the sun and in their perfect V-of-V's formation. They would be accompanied by 20 or more Zeroes, cavorting in batches of 3, nearby. Their bombing was accurate …

But the US Marine fighter squadrons based on Guadalcanal were fighting back. Known as the ‘Cactus Air Force’, after the codeword for the island airfield, among them were some exceptionally skilled and talented flyers who would become legends among airmen. Before they reached such acclaim, they had a lot of learning to do.

The first thing I knew my wingmen were gone. Attacked from above by a swarm of other Zeros, they had dived out of formation, and a Zero which had been hiding on top of the clouds was on my tail, sending a sizzling stream of tracers a few inches from my head.

Around the perimeter of the airfield the Marines, now reinforced by the US Army, would face a series of suicidal Japanese attacks. John Basilone was just one of the men who distinguished themselves, awarded the Medal of Honor for grimly holding on to his position.

His fifteen-man squad found themselves at the brunt of an attack by over a thousand Japanese infantry. They were trying to overcome the U.S. Marines' position by sheer weight of numbers. They almost succeeded.

While the enemy was hammering at the Marines' defensive positions, Sgt. Basilone, in charge of 2 sections of heavy machine guns, fought valiantly to check the savage and determined assault. In a fierce frontal attack with the Japanese blasting his guns with grenades and mortar fire, one of Sgt. Basilone's sections, with its gun crews, was put out of action, leaving only 2 men able to carry on.

The action was no less intense in the Solomons Seas where the naval battles continued, including the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, as the US Navy, at considerable cost, gradually began to prevail.

From the time of the first radar report of enemy planes at 0957 (when they were coming in, distance 45 miles) until 1100, there were almost continuous reports of bogies coming in and going out.

Operation Watchtower also included landings on the islands of Tulagi and Florida in the southern Solomon Islands. For a good summary of the campaign from a military perspective see the chapter in Amphibious Assault: Manoeuvre from the Sea, edited by Tristan Lovering.