'Arras Counter-Attack 1940'

21st May 1940: An excerpt describing part of the only British armoured attack of the short campaign in France

On the 21st May, the British Expeditionary Force mounted its only significant armoured operation of the 1940 campaign in France. The British, from Churchill down, had been trying to encourage the French to mount a counter-attack. The 21st May operation was first planned as a two-pronged pincer movement to cut off the German spearhead advancing to the French coast. The British would attack south-west, while a separate French force would attack in the opposite direction. For a variety of reasons, the French participation never materialised. So the British attack went ahead any way.

Tim Saunders has written a number of titles reconstructing battles, where he includes the personal testimony of participants. I have previously featured ‘Hill 112’, from the 1944 Normandy campaign. The following excerpt comes from Arras Counter-Attack 1940:

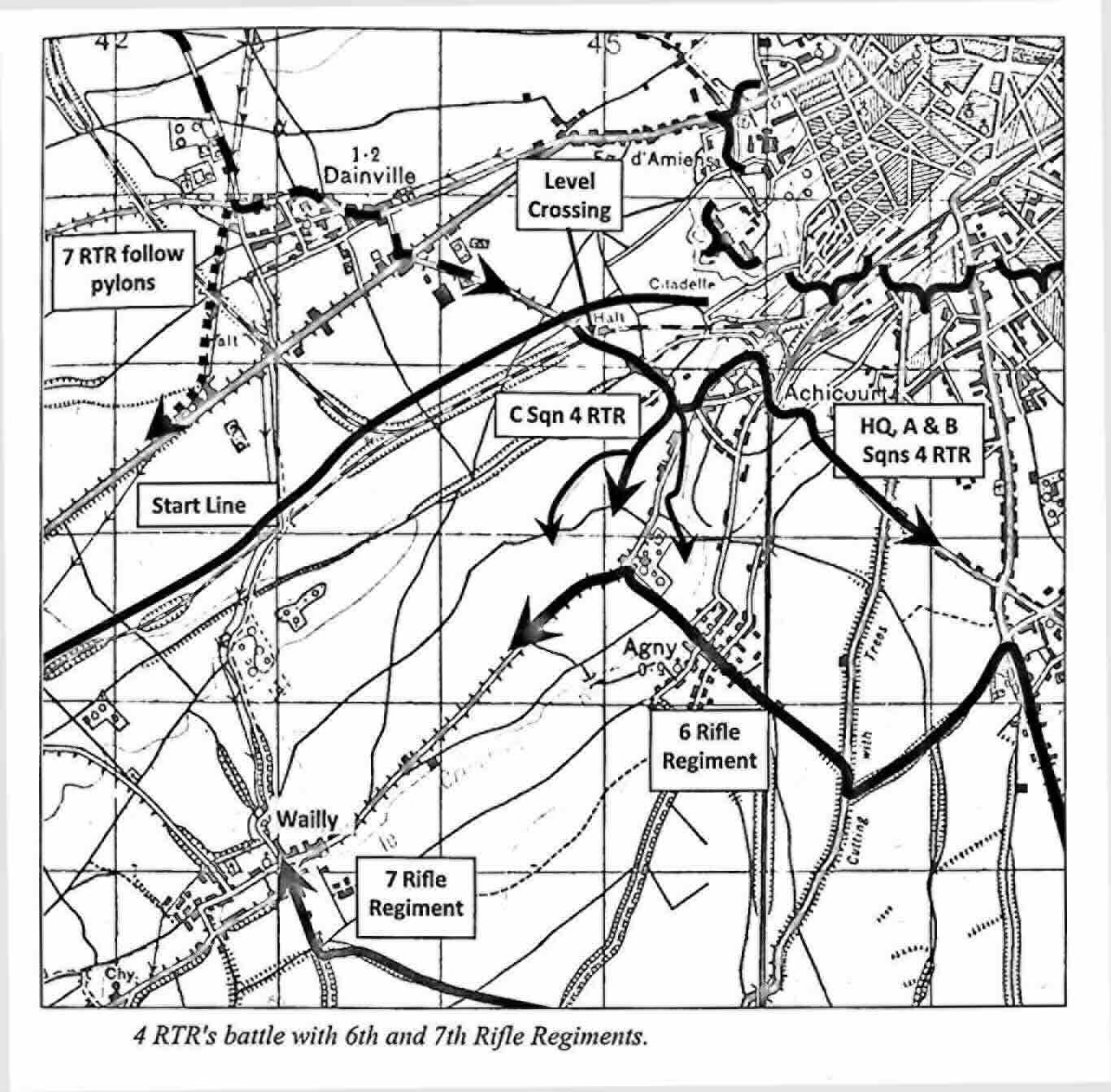

4 RTR [4th Royal Tank Regiment] reached its start line on time at 1400 hours, where there was some delay before crossing the railway line as the level crossing gates were closed. Railway lines were considered to be very much of an obstacle to the tanks of 1940 and with deeply-ingrained training not to damage property, there was a pause! Eventually, there were instructions ‘to drive through the bloody thing’ and a light tank did the deed.

On the battalion’s right, however, C Squadron’s leading tanks, despite concerns that it might be electrified, started to cross the railway but it was a slow process and not all managed to get across, with some tanks becoming stuck on rails and in some places steep embankments or cuttings, most of which would cause little problem to the tanks of just a few years later.

Shaking out into formation, two squadrons abreast, the tanks climbed onto a slight crest and straight into the flank of the 1st Battalion, 6th Rifle Regiment of the 7th Panzer Division. The trucks carrying the German infantry had turned south-east out of Agny and were strung out down the road D3 to Wailly following at least 6 miles behind in the wake of the 25th Panzer Regiment.

Second Lieutenant Peter Vaux recalled:

We had come straight into the flank of a German mechanised column which was moving across our front. They were just as surprised as us, because they were in the trees, and we were immediately right in amongst them. And for some quarter of an hour or so there was a glorious ‘free for all’. We knocked out quite a lot of their lorries; there were Germans running all over the place.

Brigadier Douglas Pratt, Commander 1 Army Tank Brigade, wrote in a letter penned shortly after the battle, even though he personally was not forward with 4 RTR:

We got about four miles forward before any infantry of ours appeared in sight. During this time, we played hell with a lot of Boche motor transport and their kindred stuff. Tracer ammunition put a lot up in flames. His anti-tank gunners, after firing a bit, bolted and left their guns,even when fired on at ranges of 600 to 800 yards with machine-guns from Matildas. Some surrendered, and others feigned dead on the ground!

Brigadier Pope was also watching from a vantage point at the Arras racecourse to the north of Dainville:

There was a slight haze which made detailed observation difficult, but it did my heart good to see the manner in which the Brigade went into action. There was a good deal of machine-gun and anti-tank gunfire more than I expected, but the tanks pushed on without faltering and as they passed the fire was subdued.

The German infantry were panicked by the eruption of British armour on their flank and did their best to escape. Many, however, attempted to surrender but tanks without infantry cannot effectively take prisoners and therefore many Germans who surrendered subsequently ‘went to ground’ as the British tanks passed by and lived to fight another day. If there had even been a small number of DLI infantry who could have ridden on the tanks to the start line, the story and impact of this encounter may have been more serious for the Germans and also more long-lasting.

However, without properly working radio communication across the battalion, control of the squadrons and even troops was difficult; tank commanders fought almost independent actions. Even so, Lieutenant Vaux recalled that

‘we had a highly successful battle. I don’t know how many German vehicles we set on fire. At that moment we did not see why we shouldn’t go all the way to Berlin.’

With their tails up, 4 RTR drove on through the enemy, with A and B squadrons heading left towards Achicourt and their Phase One objective on the River Cojeul beyond, while on the right C Squadron pushed on towards Agny.

Thus far the battle had been one-sided but surprise was not the only thing that 4 RTR had going for it. Brigadier Pratt wrote:

None of his anti-tank stuff penetrated our Mk Is or IIs and nor even did his field artillery which fired high explosive. Some tracks were broken and a few tanks were put on fire by his tracer bullets, chiefly in the engine compartment of the Mark Is. One Matilda had fourteen direct hits from enemy 37 mm guns and it had no harmful effect, just gouged out a bit of armour!

As we will see, Brigadier Pratt was correct about the inadequacies of the 37mm gun but direct fire from German 105mm field artillery was to contribute significantly to the outcome of both RTR battalions’ attacks.

Troop commander WO 3 Armit’s experience in his Mk I tank bears out the Germans’ inability to penetrate the armour of the Mk I or the Matilda with the 37mm. He advanced under heavy anti-tank fire, engaging with his .50 Vickers machine gun which soon jammed. Consequently, with no effective weapon, he used the tank, charging the line of six deployed 37mm anti-tank guns. The German gun crews managed to get one gun away, while the remainder of the gunners ran off. Armit, ably supported by Sergeant Strickland, drove over the remainder of the abandoned guns, crushing them under their tracks.

As a result of the 1940 campaign, the 37mm earned the nickname the ‘Panzer' Knocker’ among the German anti-tank gunners. Its inability to knock out the heavier Allied tanks of 1940 was the spur to develop much better tank and anti-tank guns, which demonstrably gave the Germans the edge in this field later in the war.

Some 3 miles further back Lieutenant Colonel Miller of 6 DLI could hear the tanks in action and, having fought alongside tanks in the First World War, knew that any ground gained would have to be secured and held by his infantry. Therefore he urged his very tired and footsore men onwards towards the sound of battle.

Hurrying along in the wake of the tanks the Durhams started to arrive on the scene of 4 RTR’s action south of Dainville. Remarking on the aftermath of the tanks’ encounter with 6th Rifle Regiment, Major Jeffreys recalled

we found a lot of German dead and took a lot of prisoners. They came forward surrendering and very correct they were. I remember a German officer came up to me and he said, ‘Are you the senior officer around here?’ in broken English. ‘Yes,’ I said. He replied ‘I would like to personally surrender to you.’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘you can do what you like,’ and he replied I and my men would like to lay down our arms and surrender.’ ‘Alright, throw down all your stuff there. Give me your map,’ And I handed them over to a Lance Corporal to take back, and off we went.

....

[At this point they spotted a large German tank which clearly outgunned them. So Lieutenant Vaux, a key eyewitness, was sent back to seek the support of some French heavy tanks in the rear. He was unable to get them to come forward.]

...

Lieutenant Vaux returned from his abortive mission but what had happened while he was away was not immediately apparent to him:

I could see upwards of twenty tanks, down in the valley just short of a potato clamp. The Colonel’s tank was down there, a little in front of them -I could see it quite clearly, it was stationary with the flag flying from it. The Adjutant’s tank was quite close to the Colonel’s, but from where I was I wasn’t quite sure what to do, so I called up the Colonel to tell him about the French tank.

I called and I called and I called, but I got no answer, and then the Adjutant came on the air and he just said, ‘Come over and join me.’ So I motored down to the valley and as I did so I saw the Adjutant drive forward to the area of the potato clamp and start shooting, and as I got closer I saw that there were German anti-tank guns in the area with their crews running about. At that time, a good deal of fire was coming from the area of the wood on Telegraph Hill and it was very heavy fire from field-guns; much heavier than anything we had encountered so far.

I went forward through the tanks of A Squadron and I thought it very strange that they weren’t moving and they weren’t shooting, and then I noticed that there was something even odder about them - their guns were pointing at all angles; a lot of them had their turret hatches open and some of the crews were half in and half out of the tanks, lying wounded or dead. I realised then, with a shock, that all these twenty tanks had been knocked out by those big guns.

In the grass, I could see a number of black berets as the crews were crawling through the grass, which was quite long, attempting to get away - those who were not dead. I went forward as I had been told to do, and joined the Adjutant in front of some German anti-tank guns and we began shooting at them.

I remember that I owe my life to the quick-witiedness of Captain Cracroft, the Adjutant, because when we got to the potato clamp I found that on the other side of it were half a dozen Germans and so I drove up to them from my side of the potato clamp and gave fire orders to my gunner to fire down into the potato clamp but he couldn’t depress the gun far enough.

All this time I was standing on the seat of my tank shouting at the gunner and calling to the driver to reverse a bit so that we could get the bullets down low enough, and little did I think that behind me there was a German lying on the ground, with his rifle resting on a pack, drawing a very careful bead on the back of my neck. Well, the Adjutant, I heard later - not till I got back to England - pulled out his revolver and, quick as a flash, he shot the German in the throat. It must have been a jolly good revolver shot, and it saved my life.

[4 RTR had been caught in the open between a battery of German 105mm guns and a separate battery of 88mm anti-aircraft guns, deployed as field guns. Just as they had been lucky to fall across the unprotected German motorised column, they were unlucky to advance into this area, which became a killing ground, although not planned as such by the Germans.]

© Tim Saunders 2018, Arras Counter-Attack 1940. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.