'Hill 112' - a blow by blow account

A reconstruction of the series of battles to take the position that was 'The Key to Defeating Hitler in Normandy'

One inconspicuous section of high ground in Normandy was fought over for six weeks throughout July 1944. The commanding views from Hill 112 were immediately recognised as strategically important by both sides. The struggle to take it - and hold it - led to a series of attacks and counterattacks. Tim Saunders, who has written extensively about the Normandy campaign, reconstructs the day by day struggle with many first person accounts from both sides in Hill 112: The Key to defeating Hitler in Normandy.

An excellent exposition of the fighting in Normandy through the story of one battle, pulling together the strategic and tactical perspectives alongside the personal. Complete with many photographs and charts.

‘Hold your fire, chaps, until you see the bastards’ eyes!’

On 10th July it fell to the Devon and Cornwall Light Infantry - DCLI - to make an evening attack:

The Attack

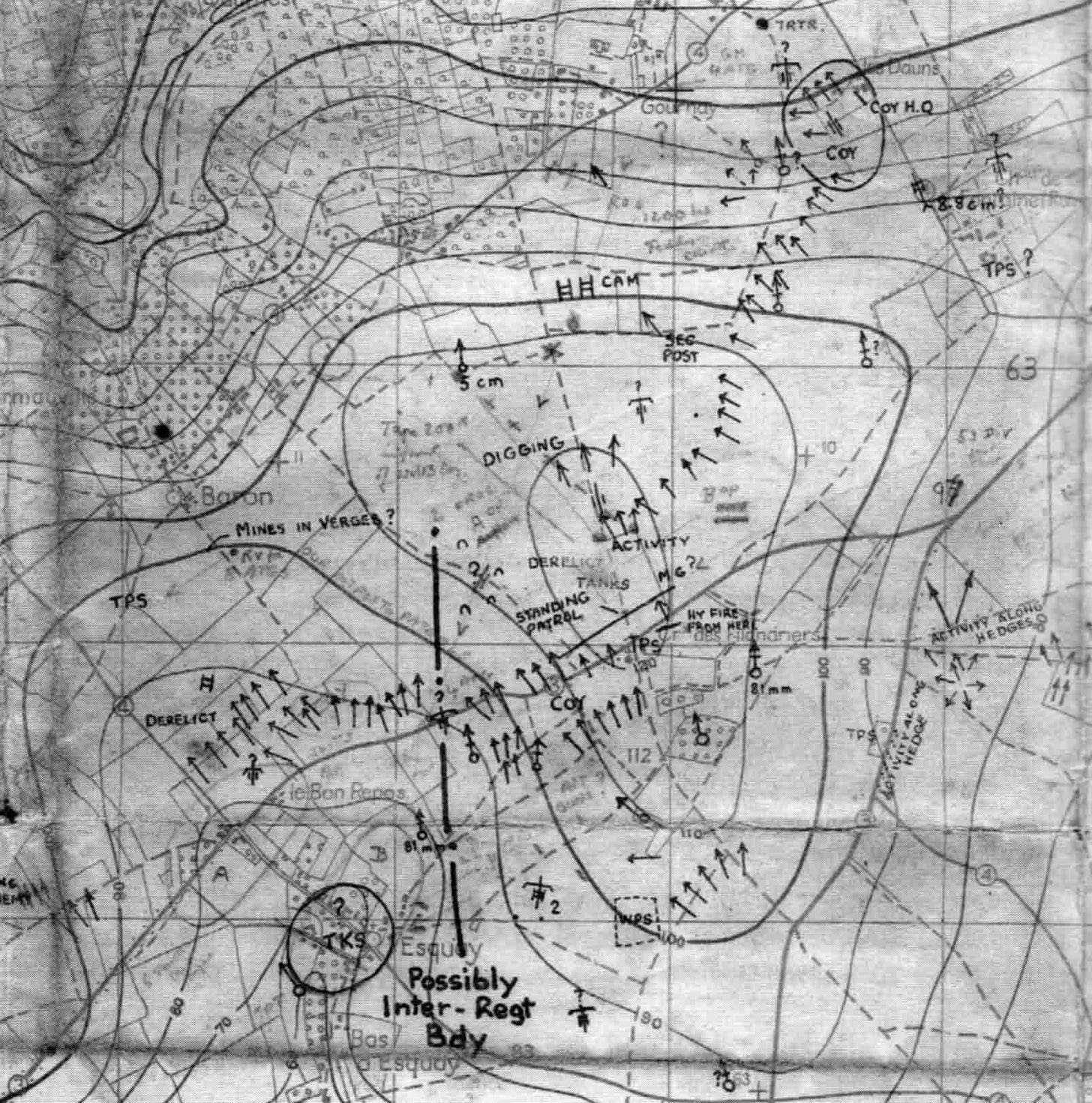

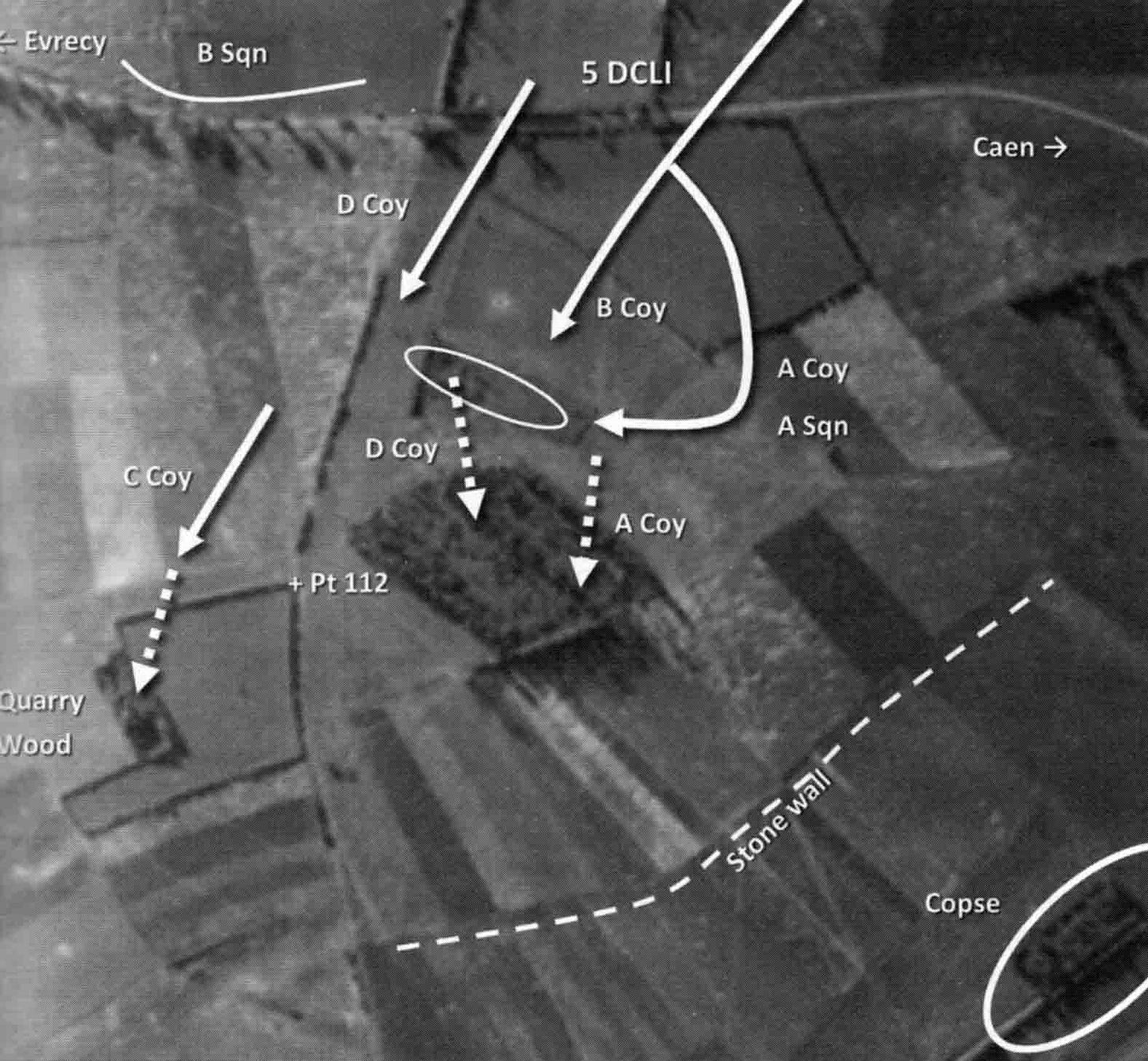

5DCLI formed up in the dead ground behind the front-line positions, at their H-Hour of 2030 advanced across the Caen-Evrecy road. A Squadron was, however late arriving at the FUP and followed the reserve companies up to the northern edge of the plateau. In their absence the Bofors guns of 110 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment provided streams of rapid fire for the leading companies.

Private Gordon Mucklow, who had been transferred to the DCLI from the Warwickshire Regiment as a battle casualty replacement, recalled:

‘As we broke rough the hedge, making for the Orchard on the summit in open order,the enemy opened up with everything he had. Tracer bullets criss-crossed the fields and mortars exploded around us.’

C Company following the bombardment closely advanced quickly on Quarry Wood, but following behind them D Company ran into trouble in the area of the small orchard, as did B Company leading on the left.

The company commander Major Vawdrey was killed in the heavy machine-gun fire. Private Jack Johnson of 8th Middlesex was a part of Major Kenyon’s Mortar Fire Control party moving across the plateau to the left rear of the Cornwalls’ B Company. He recalled that:

We came under heavy fire and casualties were mounting and the attack stopped. We put our carrier in an excavation where a German tank had been hull-down. Major Kenyon said, ‘I’ll find out what’s holding us up.’ When he came back, he redirected the guns and mortars and soon we moved forward again.

The tanks and Major Roberts’ A Company were also able to manoeuvre around to the left into positions from where they could suppress enemy that had caught B Company in the open. Lieutenant Ritchie, with 9 Platoon, cleared the machine guns from the small orchard, killing most of the crews and taking the rest prisoner and a much-reduced B Company was on the move again.

Meanwhile, as Private Mucklow recalled:

We reached halfway to the orchard, pausing in a dip across the field. Stick grenades were being dirown at us from the edge of the orchard. We must have been only just in reach. The officer with us shouted ‘Throw them back’, which we did. We were elated to see we could do it with some success, as the time-delay fuses were longer than ours. The Jerries then ran from their positions.

Under heavy fire and with their own grenades falling about them, the SS Panzer grenadiers withrew from the small orchard and the now depleted B Company was able to reorganize. The attack on the orchard itself would now be undertaken by A and D companies.

Meanwhile, on the right, C Company had fared well against little opposition by veering off to the south-west, breaking through a hedge and across the paddock to Quarry Wood. Little is known of their fate.

Rottenfuhrer Zimlitz was driven from his position in the orchard by the DCLI and recalled that:

When the Tommies got into the Wood of the Half Trees [one of the German names for the orchard] we moved to our last line of retreat. It was a dry stone wall overgrown with bushes, about 100 [250] metres further down the slope. It gave good cover and a good field of fire. Behind that ditch, the slope ran downhill for 1,000 metres without a scrap of cover. We always said that we would have to hold that ditch or die in the attempt. Tommy never got that far.

While B Company reorganized, A and D companies resumed the advance on the orchard, but as Major Taylor described:

The enemy had beat a hasty retreat from the orchard on the flank, one platoon of D Coy, caught up in the excitement of battle, followed their commander, Lieutenant Carmelli, beyond their objective and down into the valley in hot pursuit of the Germans.

Carmelli, a Canadian serving with the British army under the CANLOAN scheme, was killed, along with most of his men. Perhaps a foolish action, but Major Bob Roberts, A Coy commander, was to write later: ‘No one who saw it will ever forget their courage and determination.’

Having broken into the orchard and driven out the defenders from its forward edge, Majors Roberts and Fry decided to hold the line of the ditch and hedge that divided it in two. The forty-strong remnants of B Company were ordered to join them under cover of the smokescreen that sealed off the orchard, and the companies sorted themselves out into some semblance of order.

The Defence of the Orchard

With the orchard occupied, Sergeant Frank Grigg, the Signal Platoon’s line sergeant, was waiting at 5 DCLI’s Rear Battalion Headquarters behind 4th Somerset LI’s front line:

Hardly noticing that the shelling has eased off (too bust’ digging), the signal officer appears. ‘I want a line party to take a line to the wood,’ he says. Most of the signallers were already deployed with their companies and those handy were nearly all NCOs. Standing with one foot up on a dead cow, he says, ‘Now chaps, here’s medals on your chest.’ Sergeant Gould, a Londoner, mutters ‘I don’t want any bloody medals on my chest’, but this is ignored or drowned out by shelling.

Where is our 15-cwt truck with all the gear? It must be at the rear. Three of us take a drum of cable each, phone, pliers, tape and earth pin. Off we all go into the darkness. ‘This way,’ says the signal officer as he dashes ahead. I can’t go that fast as I pay out the cable, stumbling along the rough ground. Nearly the end of the drum. Suddenly the signal officer turns directly to the right. ‘God, where’s this dammed wood?’

The drum gives a wrench. ‘Wait,’ I hiss, ‘we have to make a joint.’ Kneeling down, Jack Foster and I struggle to make a reef knot in the cable, twist tape round. Suddenly a Very light lights up the whole screen. We freeze, motionless! London humour now comes from Sergeant Gould: ‘Whoever saw a drum of cable growing out of a tree!’

Blackness as the light goes out. We go on. Damn this noisy spindle on the drum; bound to give us away. God! End of second drum ...

Another Very light. This time from a tank coming around the end of the wood. Friend or foe? We don’t know. It starts firing tracer bullets at us. ‘Get down, Sergeant Grigg,’ shouts the signals officer, ‘they’re after you!’ He’s right behind me so I say: ‘Well he must be after you too sir!’ but the Very light gave us a glimpse of the hedge and Colonel James just inside.

The signals officer and Jack Foster jumps over with the telephone and I clamber in with the cable. Hastily we connect the telephone. ‘Hello, Rear HQ,’ says a voice. Good, we’re through, thank God!

Suddenly we’re aware of the tank to our left, which has now moved closer. It stops, out jumps a crew member, ‘Comrades, comrades,’ he shouts. ‘Shoot him,’ yells somebody - but signallers have no weapons! ‘Here’s a Very pistol,’ says someone. The signals officer takes the pistol and shoots the poor sod. He reeled like a Catherine wheel on fire! And the tank roared off.

Having laid the line, signaller Privates Foster and Luther were ordered to stay with the battalion’s advanced headquarters:

While holding on tight to the No. 18 set in the run across the field my rifle had slipped off my shoulder and into a shell hole, but it was a simple matter to get a replacement from one of the dead bodies I had passed on the way. The nearest happened to be a Somerset chap from their battle before us ... his fingers were locked in death around the trigger guard and had to be prised apart, God rest him as I thought then, and smartly into the nearest pit where Luther had put our gear and was then busily digging deeper.

By great good chance the first officer we saw then was the CO, Colonel Dick James, who decided that our pit should be his command post. Also, that as his own signaller, Leslie Williams, had been diverted to another part of the wood then Luther and I should take over that duty from him.

With the light now fading and the anti-tank guns forward, the Churchills of A Squadron withdrew and the Cornwalls dug in as fast as they could, while the Germans engaged with shell and mortar fire. The situation was already precarious, and Colonel James went around the position to inspect progress and ordered the Carrier Platoon to come up immediately to strengthen his defences in the orchard.

British artillery intelligence reported that there was plenty of incoming enemy shell and mortar fire but very little from Nebelwerfers. With their telltale trails, it is assumed that they had suffered heavily from counter-bombardment during the day. In addition, their launch signature as it grew dark would have made them particularly vulnerable.

…. he just hails down his fire until, as we say, ‘the coffee-water is boiling in our arses’;

Counter-Attack

At 2100 hours a report originating from III Battalion 21 SS Panzergrenadiers stating that ‘British tanks have taken Hill 112’ started to make its way up the German chain of command. Consequently, Obersturmfuhrer Schroif ordered the usual immediate counter-attack, in which the remaining Tigers of 102 Schwere Panzer Battalion and two companies of SS infantry advanced up onto the plateau. Radio-operator in Unterscharfuhrer Fey’s Tiger 134, Heinz Trautmann, wrote:

With the speed and precision resulting from long-practised, much-hated drill, we all swung into our seats, as our Company' was due to attack in a few minutes. On the call, ‘Net in’, I tuned my receiver and put on headphones and microphone. The frequency' scales begin to light up, the current hums.

2100 hours (Allied time). Above our heads, the turret hatches clang shut. The driver starts the engine, and we move forward with a jerk. Through our narrow vision slits, we can see the bushes and branches we have tied on for camouflage start to fall off. We make a half-turn to the right, our tracks screeching. In a long line, our sixteen Tigers move obliquely onto the road. All we can see through the slits are trees to left and right, and the stern of the tank in front.

Then a short halt, as we reach the start of the slope, and fan out into a broad wedge-formation. There are thick bushes growing halfway up the slope, and that is where we must go to take up firing positions. The enemy won’t show himself, let alone come out and fight, he just hails down his fire until, as we say, ‘the coffee-water is boiling in our arses’; but as long as he only hits the ground, we are safe from a hero’s death. For our infantry', however, who had no armour plate, it was different; they couldn’t fire a shot, they just crouched at the bottom of their trenches and waited.

Down came a barrier of defensive fire such as we East-Fronters had never known; the Russians had never as many guns as this, and they did not use them in this way …

On the left: flank SS Obersturmfuhrer Schroif and his platoon of Tigers had been waiting at the foot of the southern rim of the plateau:

It was almost dark when the order came. On the right, I could see the Tigers of No. 1 Company already moving on to the slope. My objective was the Kastenwaldchen [another German name for the orchard]. We got to within about 300 metres of it. I halted the Company and opened fire. I pushed forward on the left into a hollow in the ground. We couldn’t have been more than 100 metres away. We fired with machine guns and sent high explosive into the treetops. Machine-gun fire rattled on the armour and we could see the muzzle flashes of anti-tank guns.

No. 1 Company’s Tigers pressed on to the crest but, Unterscharfuhrer Fey wrote:

Down came a barrier of defensive fire such as we East-Fronters had never known; the Russians had never as many guns as this, and they did not use them in this way; and then came a thick smokescreen. Our attack folded up at the foot of the hill, before we even got onto the slopes.

Even so, without panzer support, the Panzergrenadiers came through the orchard’s southern hedge. Major Roberts describes what happened:

We had no difficulty in repulsing the infantry, the fire-discipline being first- class and both companies giving the Boche absolute hell. It was grand to hear the section commanders shouting out their orders: ‘Hold your fire, chaps, until you see the bastards’ eyes!’

© Tim Saunders 2022, 'Hill 112: The Key to defeating Hitler in Normandy.'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today …

The 508th PIR's bloody 4th July

I had no more than hung the phone back on the tree than the Germans put a round of 81mm mortar into the branches. I think I heard it coming but took a dive too late. I was hit in the back by two shell fragments. It felt like someone stuck a fence post in my back.

So if we were out to capture a prisoner it meant first of all penetrating the enemy line. We had to take great care in our preparation: running shoes, no loose clothing to catch on anything, dark faces, no identification papers, just dog tags, Sten guns, knives, garrotte and grenades. Our weapons would be wrapped in cloth - no accidental noises.