Operation Colossus

The fate of the only Italian to participate in 'The First British Airborne Raid of World War II'

On the 10th February, the British launched their first parachute raid of the war. Early Parachute training began by trial and error, and parachute operations followed on similar lines. There was much yet to be learnt about conducting ‘Special Forces’ raids in enemy territory, not least how members of such raiding parties could be exfiltrated with a reasonable chance of success.

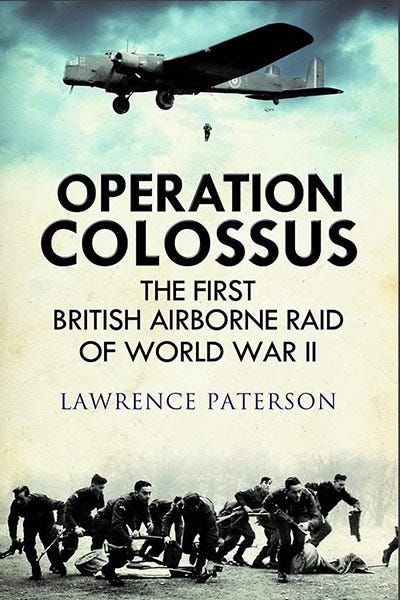

A comprehensive account of the raid, incorporating many first-person accounts, was published in 2020: Operation Colossus: The First British Airborne Raid of World War II. This excerpt looks at the fate of the one man on the raid who had not trained as a Commando.

Fortunato Picchi had emigrated to Britain in 1921 and rose to become the Head Waiter at the Savoy Hotel, eventually getting British citizenship. With strong anti-fascist sympathies, he had volunteered for the Army in 1940 but had soon been recruited by the Special Operations Executive. At the age of 42, Picchi might have found Commando training rather a challenge, but he successfully passed the Parachute course at Ringway in late 1940.

He was then given the identity of a French soldier, Private Pierre Dupont, and joined ‘X Troop’ as one of three interpreters. He appears not to have received very much training from the Special Operations Executive. After the attack, the raiding party split up into three groups to make their escape, and the group Picchi was with was captured on the 12th December:

At Poggioreale prison on the first morning of interrogations, officers were questioned separately from the enlisted men, taken one at a time to face a Bonsignore man dressed in civilian clothes, seated behind a desk and flanked by two black-shirted men of the MSVN1 who, though denied jurisdiction over the prisoners, exercised their right to supervise the interviews.

The interrogations themselves followed a predictable and nearly identical pattern for each man. The interrogator introduced himself as the commandant of the prisoner of war camp they were likely to be sent to, and merely wanted to check details of the prisoners for the International Red Cross. Behind this transparent fiction were attempts to put the captives at ease, asking apparently innocuous details of personal backgrounds and next of kin, before interjecting more specific questions of a military nature. Predictably, none fell on fertile ground and the prisoners declined to answer questions, or, at best, gave misleading answers intended to amuse themselves at the interrogator’s expense.

Meanwhile enlisted men were also interrogated singly, probably handled differently by the Italians as they were frequently threatened with summary execution for having waged war on the civilian population, their only hope of salvation being full and frank confessions of their acts and any other information that was asked of them.

None of the British soldiers divulged anything of any use to the Italians, also averting potential disaster when asked if they had arrived in Italy in civilian clothes. If so, they could have justifiably been considered spies and shot, but fortunately no man struggled with the truth that they had all worn battledress and carried their accompanying pay books.

While the Britons seemingly shrugged off the interrogation attempts, [ ... ] there was immediate concern was for Picchi, who faced his own impending interrogation with growing anxiety. Picchi had confided to Deane-Drummond that he was intending to make a clean breast of everything when confronted by his interrogators. Picchi clung to his certain belief that what he had done by taking part in Operation Colossus was in the best interests of his country. He was a patriot, first and foremost, and harboured hopes that other ‘true Italians’ would see his actions for what they were: a blow aimed at Mussolini’s fascist empire, not the Italy that it currently dominated.

Naïve and idealistic such beliefs may have been, but they originated from honesty and an integrity that would be unable to maintain the ruse of his French identity for long under skillful questioning. Somewhat ironically, Picchi was the sole representative of the secretive Special Operations Executive present in Operation Colossus, and yet perhaps the least prepared to counter robust questioning.

Deane-Drummond urged him to stick to his cover story, and not deviate beyond name, rank and serial number, which, after all, was all that the interrogator was entitled to receive.

However, by the end of the first day of questioning, Picchi emerged from the interview room despondent, returning to his cell in a state of utter dejection, shivering and staring unseeing at the opposite wall.

His cover had crumbled rapidly as Major Giuseppe Dotti, head of the C.S. Section (counter-espionage) of the ‘Bonsignore’, later attested in a statement provided on 21 August 1944, after the Italian surrender:

On investigation by the military authorities of the area, the Carabinieri and the police, it was possible to arrest some of the parachutists themselves, among whom there was a certain Peter Dupont. Suspicions were aroused by his perfect Italian and Florentine accent, and on interrogation he confessed that he was an Italian citizen. He was, in fact, identified as Fortunato Picchi, born at Carmignano (Florence).

Picchi had indeed been identified, the Questura (police HQ) of Florence quickly finding his ageing mother, brothers and sisters who all were visited and questioned, and later collectively persecuted by the fascist authorities for the remainder of the war. Letters and photographs of Fortunato were confiscated as evidence, and even former work colleagues at the Grande Albergo Reale in Viareggio were interrogated and shown a mugshot of the dishevelled prisoner, confirming that it was indeed him.

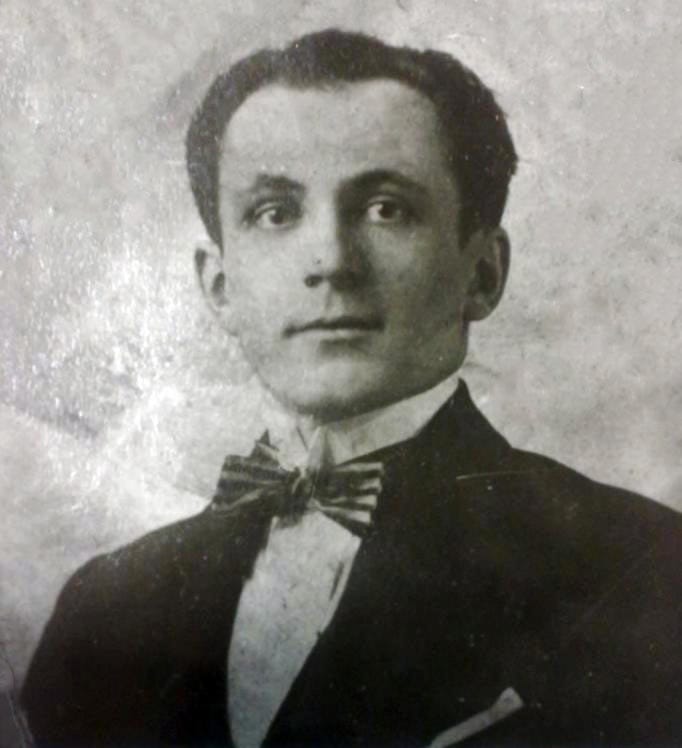

A portrait photograph taken of the young Fortunato before his emigration to Britain was forwarded to the special prosecutor’s office and submitted as evidence, stamped and certified on 17 February as genuine by the Florence Questura. As night fell, Picchi eventually succumbed to sleep, though shivering and mumbling to himself as if troubled by dreams. Doug Jones remembers him waking, whereupon he attempted to calm the emotionally drained Picchi, the two men sharing the same threadbare blanket until dawn’s weak light filtered through the high window.

Meanwhile, at some point on the night of 14 February, Rome had finally issued a War Communiqué that officially released the news of ‘Operation Colossus’ internationally:

During the night of February 10th-11th (Monday night) the enemy dropped detachments of parachutists in Calabria and Lucania. They were armed with machine guns, hand grenades, and explosives. Their objects were to destroy our lines of communication and to damage the local hydro-electric power stations.

Owing to the vigilance and prompt intervention of our defence units all the parachutists were captured before they were able to cause serious damage. In an engagement which took place one gendarme and one civilian were killed. It has not yet been decided whether to treat these British parachutists as prisoners or spies.

For Picchi, there was no doubt. The next morning, guards came for him and he was escorted from the cell bound for incarceration and trial in Rome. None of his X Troop comrades ever saw him again.

...

[Fortunato Picchi was sent for trial at a special fascist tribunal.]

...

In Rome such sessions were held in the large Hall IV of the Palace of Justice and wore a guise of great solemnity. The President and judges were all clad in the uniform of the MSVN as Picchi was led into the room on Saturday 5 April, climbing from the basement via a stairway on which was written ‘Death to traitors! Black shirts will give you lead!’

The ‘trial’ was swift, little defence offered and two uniformed Carabinieri flanking Picchi were equipped with gags should the defendant try to sully the solemnity of the occasion by mouthing his own words in defence - or defiance. Condemned to death, Picchi was taken to Fort Bravetta where he spent his final night. There, before dawn, he was allowed to pen a final letter to his mother.

My dearest mother,

After so many years you receive a letter from me. I’m sorry, dear mother, for you and for everyone at home for this misfortune and the pain that will cause you. Now all that remains in the world both of pain or pleasure is over for me. I do not care much about death, I only regret my action because I, who always loved my country, must now be recognised as a traitor. Yet in conscience I do not think so.

Forgive me, dear mother, and remember me to all. I ask you above all for your forgiveness and your blessing, because I need it so much. Kiss all my brothers and sisters and to you, dear mother, a hug, hoping, with the grace of God, to be reunited with each other in heaven.

With many kisses, your son, Fortunato.

Long live Italy!! Sunday, April 6, 1941.

At 7 o’clock that morning, Fortunato was led to the embankment of the fort’s firing range and placed on a chair with his back to the assembled firing squad of state policemen, the method reserved for those found guilty of treason. Within minutes, he was dead.

© Lawrence Paterson 2020, ‘ Operation Colossus: The First British Airborne Raid of World War II. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

Voluntary Militia for National Security (Italian: Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts.