Potsdam - the end of the war in Europe

The final conference between the Allies - An excerpt from 'Churchill and Stalin - Comrades in Arms During the Second World War'

During the course of the war Churchill forged a close working relationship with Stalin, communicating with him directly with many letters and official messages but also meeting him for a series of conferences between 1942 and 1945. He had attempted to warn Stalin of the imminent German invasion - Barbarossa - in the spring of 1941 and immediately recognised the importance of coming to the aid of Soviet Russia once it began.

Stalin had a beguiling ability to build relationships with the Allied leaders - Churchill, Roosevelt and Truman - despite the dramatic gulf between them in differences in world view and values. The original documents collected in 'Churchill and Stalin - Comrades in Arms During the Second World War' sheds light on the fascinating evolution of a personal relationship that altered the course of world history. The authors accompany these documents with an expert and comprehensive commentary on their context.

By 1945 the reality of United States power was becoming ever more manifest and this was all too evident at the conference where Churchill and Stalin met for the last time - Potsdam:

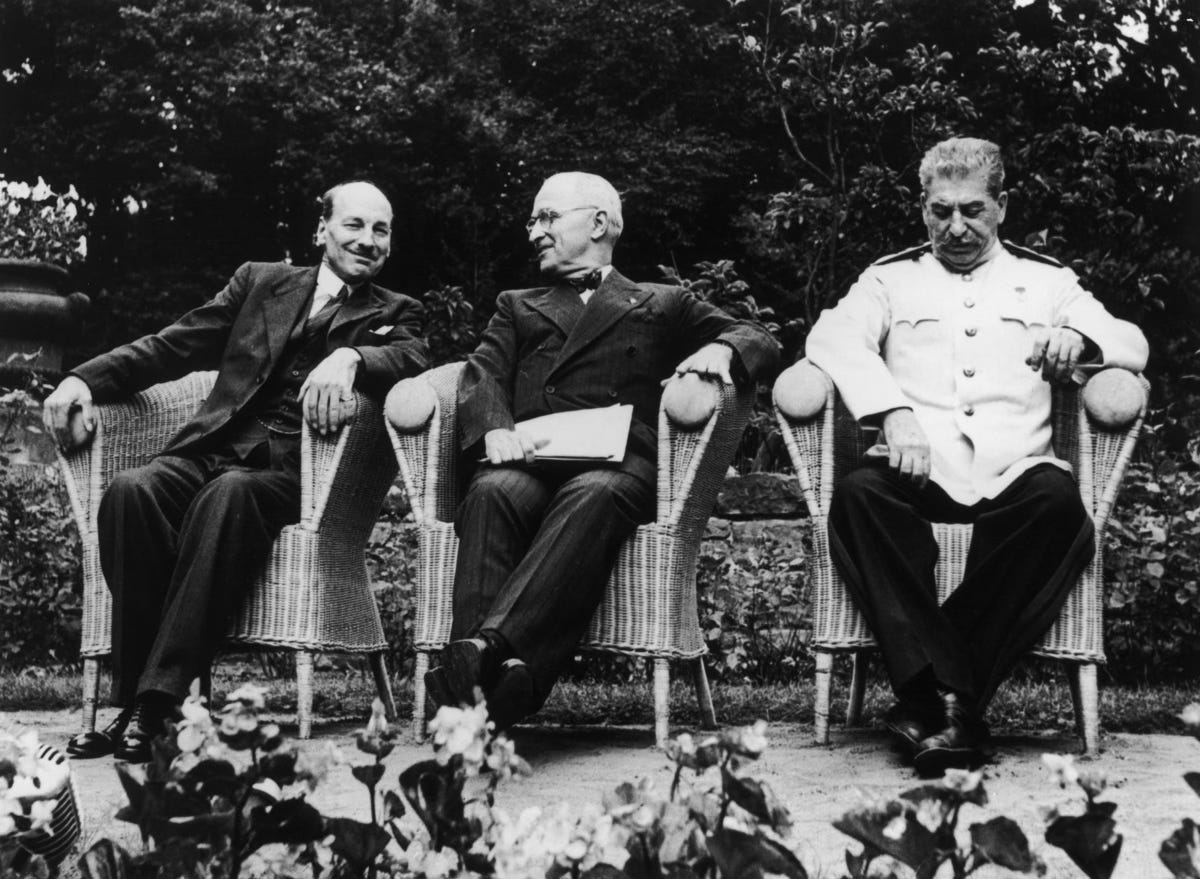

In personal terms the relations between Churchill, Stalin and Truman never achieved the intimacy of Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at Tehran and Yalta. But the new Big Three were pretty friendly with each other and the conference records are full of good humour, jokes, laughter and of efforts to avoid confrontation and deadlock in negotiations. The Prime Minister was ‘again under Stalin’s spell’ , complained Eden. ‘He kept repeating “I like that man’” .

At the time Truman thought that Stalin was ‘straightforward’ and ‘knows what he wants and will compromise when he can’t get it’. Later, Truman recalled that he had been a ‘Russophile’ and thought he could live with Stalin; indeed he ‘liked the little son of bitch’ .

Stalin was his usual charming self at the banquet he hosted. After a piano concert by leading Soviet artistes Truman got up and played some Chopin. According to Birse, the British interpreter, ‘Stalin applauded with enthusiasm, remarking that he was the only one of the three with no talents; he had heard that Churchill painted, and now the President proved that he was a musician’

There were, of course, sharp political differences at Potsdam, prolonged negotiations and hard bargaining. Stalin also had to contend with the ever more marked tendency of the British and Americans to line up together against the Soviets in negotiations. But there were Anglo-American differences too. As James F. Byrnes, Truman’s Secretary of State, joked at the conference: one gets the impression that when we agree with our Soviet friends, the British delegation withholds its agreement, and when we agree with our British friends, we do not obtain the agreement of the Soviet delegation. (Laughter).

Stalin’s first meeting at Potsdam was with Truman on 17 July. Stalin began by apologising for arriving a day late at the conference. He had been detained in Moscow by negotiations with the Chinese and his doctors had forbidden him to fly to Berlin. After an exchange of pleasantries Stalin listed the issues he would like discussed at the conference: the division of the German fleet, reparations, Poland, territorial trusteeships, the Franco regime in Spain. Truman was happy to discuss these issues but said the United States had its own items for the agenda, although he did not specify what these were.

To Truman’s statement that there were bound to be difficulties and differences of opinion during the negotiations, Stalin responded that such problems were unavoidable but the important thing was to find a common language. Asked about Churchill, Truman said he had seen him yesterday morning and that the Prime Minister was confident of victory in the British general election. Stalin commented that the English people would not forget the victory in the war, in fact they thought the war was over already and expected the Americans and Soviets to defeat Japan for them.

This provided Truman with an opening to remark that while there was active British participation in the war in the Far East, he still awaited help from the USSR. Stalin replied that Soviet forces would be ready to launch their attack on the Japanese by the middle of August. This led to the final exchange of the conversation in which Stalin indicated that he was sticking to the agreement at Yalta on the terms of Soviet participation in the Far Eastern war and did not intend to demand anything more.

Stalin’s conversation with Truman was friendly enough but it did not match the bonhomie he had achieved with Roosevelt at Tehran and Yalta. But Truman was new to the job, was still feeling his way with Stalin and, unlike his predecessor, had not engaged in a long wartime correspondence with the Soviet leader prior to meeting him.

Stalin’s private chats with Churchill were much cosier. At their first meeting, after the opening plenary session on 17 July, Stalin told Churchill that he had started smoking cigars and complained that he couldn t get to sleep before 4.00am even though the war was over and he didn’t need to work so late. Churchill thanked Stalin for the hospitality that his wife had received on her recent visit to Russia and told him that Britain welcomed Russia as a great power, including a naval power (Document 130).

The bonhomie continued the next night at dinner. Stalin was confident Churchill would win the British general election and predicted a parliamentary majority of eighty for the Prime Minster. Churchill was equally effusive, saying that he would ‘welcome Russia as a great power on the sea’ and that the country had a right of access to the Mediterranean, the Baltic Sea and the Pacific Ocean. On Eastern Europe, Stalin repeated previous promises to Churchill that he would not seek its sovietisation, but expressed disappointment at Western demands for changes to the governments in Bulgaria and Romania, especially when he was refraining from interfering in Greek affairs.

Churchill spoke of difficulties in relation to Yugoslavia, pointing to the 50-50 arrangement he had made with Stalin in October 1944, but the Soviet leader protested that the share of influence in Yugoslavia was 90 per cent British, 10 per cent Yugoslavian and 0 per cent Russian. Stalin continued that Tito had a ‘partisan mentality and had done several things that he ought not to have done. The Soviet Government often did not know what Marshal Tito was about to do.’

The positive tenor of the conversation was summed up by Churchill’s remark towards the end of dinner that ‘the Three Powers gathered round the table were the strongest the world had ever seen, and it was their task to maintain the peace of the world’ (Document 131).

The next day Churchill told Lord Moran, his private doctor, that the Marshal was very amenable. I gave him a box of my cigars, the big ones you know. He smoked one of them for three hours. I touched on some delicate matters without any clouds appearing in the sky. He takes a very sensible line about the monarchy.’ Churchill continued that he thought Stalin wanted him to win the election and that the dictator had given him ‘his word that there will be free elections in the countries set free by his armies ... I told Stalin Russia was like a giant with his nostrils pinched. I was thinking of the narrows from the Baltic and the Black Sea. If they want to be a sea power, why not?’

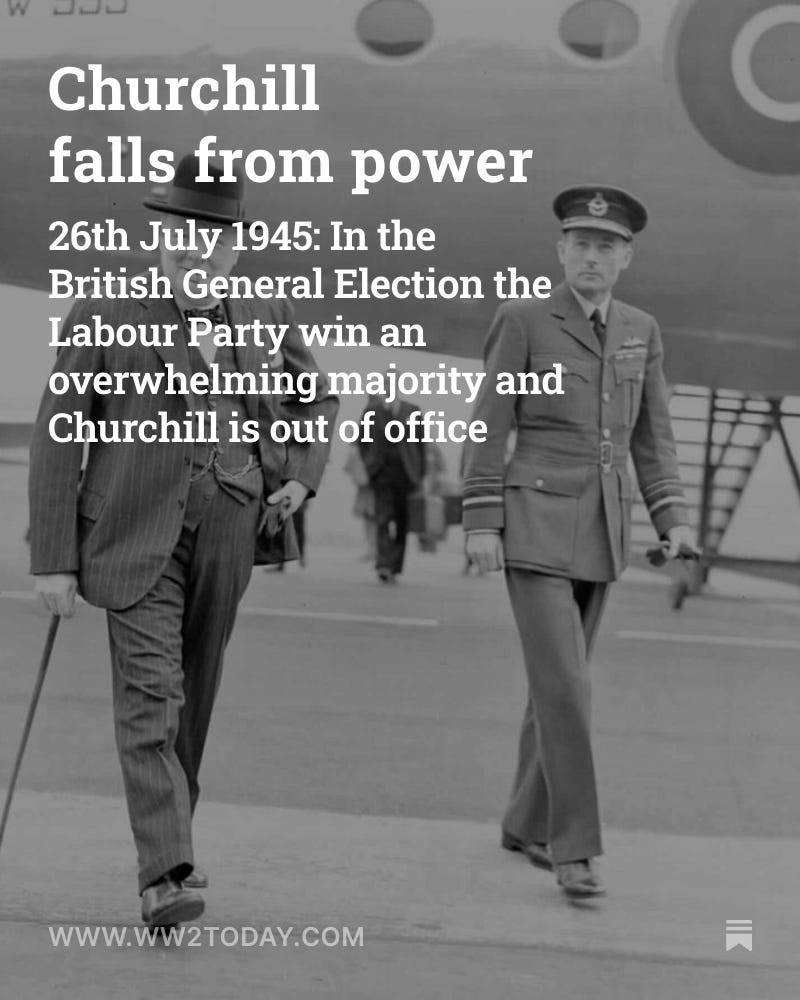

Potsdam was the last time Churchill and Stalin met. On 24 July, the day before he returned to Britain to receive the result of the general election, Churchill hosted a dinner party for the Big Three. Stalin ‘was in good humour and seemed to enjoy himself... He said that he liked these English dinners; they were simple and at the same time dignified ... At the end of the dinner [he] got up and went round the table with his dinner-card, collecting autographs.’

...

… the presence of numerous Soviet spies in the Manhattan Project who kept him abreast of Anglo-American atomic research.

The only really jarring note at Potsdam concerned the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan. At the conference Stalin told Truman that he would be ready to attack Japan by the middle of August. This pleased Truman. ‘I’ve gotten what I came for’ , he confided to his wife on 18 July. ‘Stalin goes to war August 15 with no strings on it... I’ll say that we’ll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won’t be killed. That’s the important thing.’ The British record of Stalin’s conversation with Churchill at dinner on 18 July (Document 131) states: ‘it was evident that Russia intends to attack Japan soon after August 8. The Marshal [i.e. Stalin] thought it might be a fortnight later.’

These indications were consistent with the commitment the Soviets had given at Yalta to enter war two or three months after the defeat of Germany and with Soviet military plans and preparations in the Far East, about which Stalin’s Chief the General Staff, General Antonov briefed the British and American military. The problem was that American interest in Soviet participation in the war against Japan was fading by the time of Potsdam. Militarily, it was no longer seen as vital as it had been and this view was reinforced by the successful A-bomb test on 17 July.

Truman told Stalin about the test. According to Pavlov, Stalin’s interpreter, who claimed to be the only witness to what happened, Truman told Stalin: ‘Yesterday we tested a bomb of unusual power.’ Stalin did not react at all to this news. Truman was dumbfounded and froze for several seconds as he watched Stalin walk away. Stalin’s lack of interest is explained, perhaps, by the presence of numerous Soviet spies in the Manhattan Project who kept him abreast of Anglo-American atomic research.

...

The main myth about Potsdam is that the conference marked the beginning of the Cold War. But Soviet-Western relations did not deteriorate really badly until after Potsdam and even then it took two years for the Grand Alliance to collapse and the Cold War to break out, notwithstanding Churchill’s fanning of the flames at Fulton, Missouri in March 1946.

As Michael Neiberg1 has pointed out, in 1945 Soviet and Western leaders were not grappling with the problems of the coming Cold War - about which they had no knowledge. Their reference points were the failure of the post-Versailles international order and the experience and results of the war.

Viewed from that perspective, Yalta and Potsdam represented the end of one era rather than the beginning of another. As to the future, Yalta and Potsdam pointed in many different directions, towards an enduring Grand Alliance as well as to the Cold War. The same was true of the Churchill-Stalin relationship.

© Martin Folly, Geoffrey Roberts, Oleg Alexandrovich Rzheshevsky 2019, 'Churchill and Stalin - Comrades in Arms During the Second World War'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

Michael Neiberg: Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe