U.S. locks up ethnic Japanese

19th March 1942: "Japanese-Americans" will no longer be just evacuated from the west coast area but will be detained in camps around the country

On 19th March 1942 President Roosevelt issued an Executive Order1 establishing the War Relocation Authority.

Tension was running high on the west coast of America, with a real fear of invasion. Many doubted the loyalty of Japanese-American citizens should an invasion come, and the War Relocation Authority was established to gather them up and place them in detention camps.

Milton Eisenhower, brother of Dwight, was the first Director and he explained the policy in an Office of War Information film2:

‘We knew that some among them were potentially dangerous.’

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, our West Coast became a potential combat zone. Living in that zone were more than 100,000 persons of Japanese ancestry: two thirds of them American citizens; one third aliens. We knew that some among them were potentially dangerous.

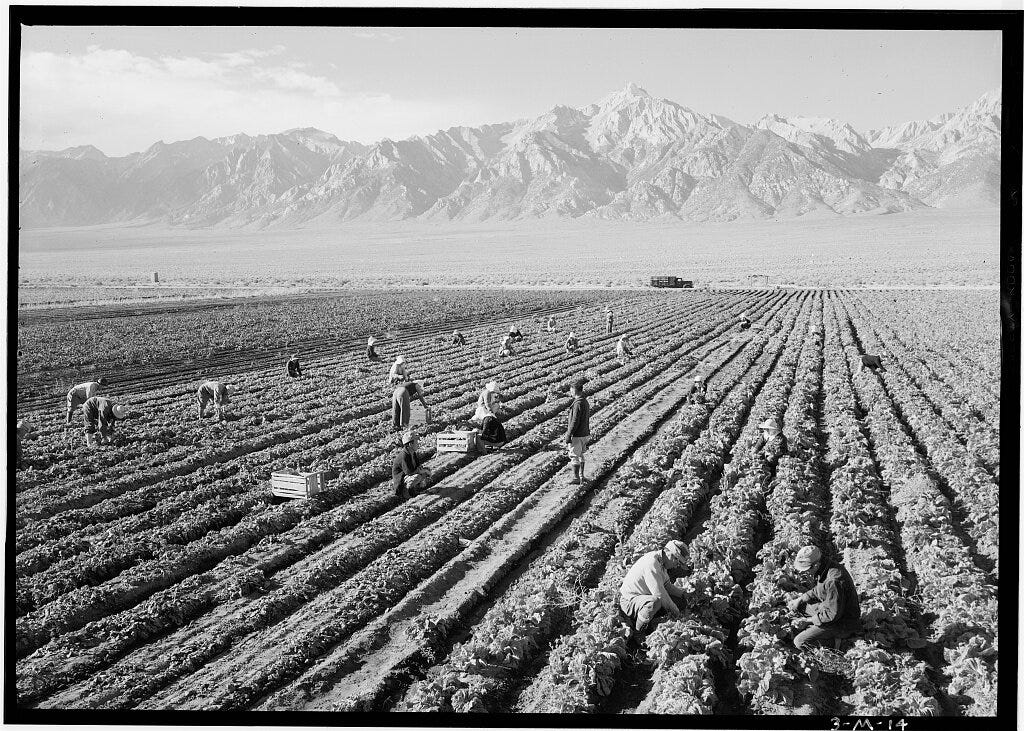

But no one knew what would happen among this concentrated population if Japanese forces should try to invade our shores. Military authorities therefore determined that all of them, citizens and aliens alike, would have to move. This picture tells how the mass migration was accomplished.

‘So the military and civilian agencies alike determined to do the job as a democracy should: with real consideration for the people involved.’

Neither the Army nor the War Relocation Authority relished the idea of taking men, women, and children from their homes, their shops, and their farms. So the military and civilian agencies alike determined to do the job as a democracy should: with real consideration for the people involved.

First attention was given to the problems of sabotage and espionage. Now, here at San Francisco, for example, convoys were being made up within sight of possible Axis agents. There were more Japanese in Los Angeles than in any other area.In nearby San Pedro, houses and hotels, occupied almost exclusively by Japanese, were within a stone’s throw of a naval air base, shipyards, oil wells. Japanese fishermen had every opportunity to watch the movement of our ships. Japanese farmers were living close to vital aircraft plants. So, as a first step, all Japanese were required to move from critical areas such as these.

But, of course, this limited evacuation was a solution to only part of the problem. The larger problem, the uncertainty of what would happen among these people in case of a Japanese invasion, still remained. That is why the commanding General of the Western Defense Command determined that all Japanese within the coastal areas should move inland.

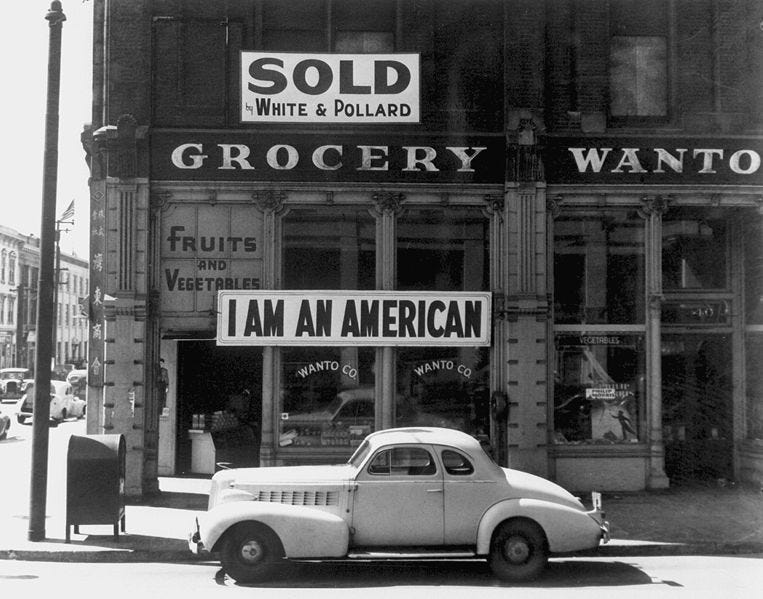

It was a broad brush procedure that swept up all Japanese Americans no matter how well established in the country, no matter how loyal to America. Many of those detained would allow their sons to volunteer to serve in the U.S. armed forces, where they would gain particular distinction and honour during the fighting in Europe.

But for those detained it often meant financial ruin and a bleak existence in remote camps3:

If this country doesn’t want me they can throw me out. What do they know about loyalty? I’m as loyal as anyone in this country. Maybe I’m as loyal as President Roosevelt. What business did they have asking me a question like that?

‘I was born in Hawaii. I worked most of my life on the West Coast. I have never been to Japan. We would have done anything to show our loyalty.’

I was born in Hawaii. I worked most of my life on the West Coast. I have never been to Japan. We would have done anything to show our loyalty. All we wanted to do was to be left alone on the coast. . . . My wife and I lost $10,000 in that evacuation. She had a beauty parlor and had to give that up. I had a good position worked up as a gardener, and was taken away from that. We had a little home and that’s gone now. . . .

What kind of Americanism do you call that? That’s not democracy. That’s not the American way, taking everything away from people. . . . Where are the Germans? Where are the Italians? Do they ask them questions about loyalty? . . .

The US Supreme Court Upheld the legality of the Executive Order in Korematsu v United States, a decision which is now widely criticised4.

Japanese Relocation, produced by the Office of War Information, 1942. National Archives and Records Administration, Motion Picture Division, July 1942.

“Interview with . . . an Older Nisei,” Manzanar Community Analysis Report No. 36, July 26, 1943, RG 210, National Archives. History Matters