The shocking news from Tobruk

21st June 1941: Churchill is in Washington when he learns that Tobruk has surrendered, while in the desert British troops are still falling back

In Washington Churchill1 was now staying at the White House. After breakfast on the 21st he went to find Roosevelt in his study:

Presently a telegram was put into the President’s hands. He passed it to me without a word. It said, “Tobruk has surrendered, with twenty-five thousand men taken prisoners.” This was so surprising that I could not believe it.

… [After getting confirmation from Britain that Tobruk had fallen]

‘I did not attempt to hide from the President the shock I had received. It was a bitter moment. Defeat is one thing; disgrace is another.’

This was one of the heaviest blows I can recall during the war. Not only were its military effects grievous, but it had affected the reputation of the British armies.

At Singapore eighty-five thousand men had surrendered to inferior numbers of Japanese. Now in Tobruk a garrison of twenty-five thousand (actually thirty-three thousand) seasoned soldiers had laid down their arms to perhaps one-half of their number. If this was typical of the morale of the Desert Army, no measure could be put upon the disasters which impended in North-East Africa.

I did not attempt to hide from the President the shock I had received. It was a bitter moment. Defeat is one thing; disgrace is another.

South African James Ambrose Brown2 was some distance east of Tobruk. They had learnt with 'stunned amazement' that contact with their compatriots within Tobruk had been lost at 2100 the previous evening.

Early in the day they were readying to defend their position, later they were warned to be ready to pull back even further. The destruction of supplies began in order to deny them to the enemy:

1500

In Tobruk, ‘every man for himself’ is the order of the hour. We will attempt to hold Sollum to make time for the overrun garrison. Those who escape will do so only by a miracle.

The passes are blown up, the coast roads are cut, the perimeter is encircled in a ring of steel. Tanks might break through but motorised infantry, never. Even men on foot will stand only a slim chance, there is nowhere to hide in the desert.

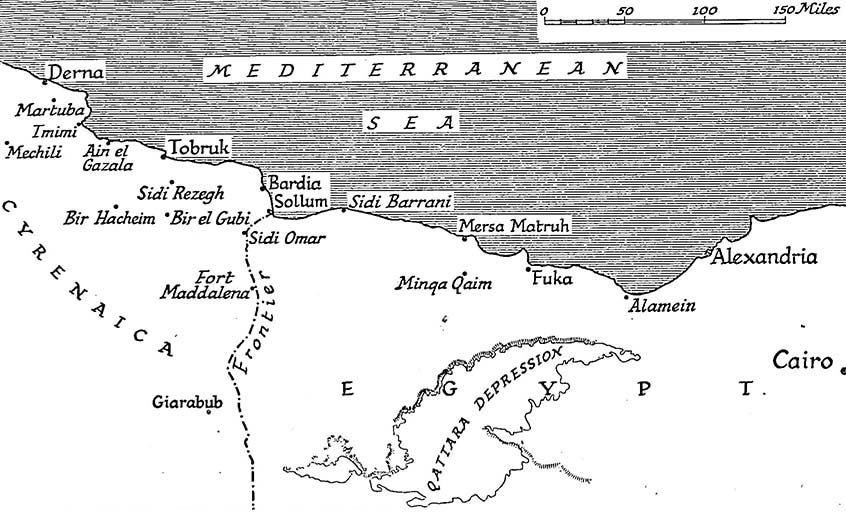

Evacuation by ship might solve the problem but the harbour is tiny and land-locked and the narrow entrance mined except for a single channel used to supply the garrison. Also, it would be a practical impossibility to raise sufficient shipping in the time available, for Mersa Matruh, the nearest big base, is twelve hours sea journey distant.

Ships that might get in will have to run the gauntlet of close-based Stukas. Today, Tobruk is a death trap, the only escape will be by swimming, in small boats or on foot by night. We believe that at least a third of Eighth Army is in Tobruk and more than half our armour.

....

‘out comes a hideous rumour - the 2nd Division had surrendered unconditionally. Simply laid down their arms. I cannot believe that this is true. A third of our army giving up without firing a shot. No, I think not.’

2100

Now that we can do nothing with it we have more water than we know what to do with. The storage tanks at El Hamra are free to all. What cannot be carried away will be poured away. We fill our water bottles, drink and fill them again but the irony is, no one has containers.

Quarter Simpson, making an issue of five cans of beer per man, tells me that the NAAFI storemen are machine-gunning stocks of beer worth £20,000. I feel an enormous apathy as I watch others rushing about with cases of canned fruit, liquor, jam. There is a mad abundance. I see men hacking tins open with bayonets, drinking the syrup and chucking the cans aside.

A man, bubbling with excitement has just run over. ‘Our composite company in Tobruk has escaped ... only one man dead.” This is Ralph Parrott’s work. Just when we are thinking that if one resolute officer can get his company out comes a hideous rumour - the 2nd Division had surrendered unconditionally. Simply laid down their arms. I cannot believe that this is true. A third of our army giving up without firing a shot. No, I think not.

James Ambrose Brown wrote one of the outstanding accounts of the Desert war in his diary, Retreat to Victory: Springboks' Diary in North Africa - Gazala to El Alamein, 1942 (South Africans at War).