The hell of a Japanese Prison ship

29th October 1942: An account of the conditions in which POWs - British, American, Australian and others - were transported by the Japanese

On the 29th October 1942 Arthur Titherington found himself somewhere in the South China Sea, destination unknown. He had been captured at Singapore and was now amongst the thousands of Prisoners of War who were being despatched to a variety of locations around the south east Asia to work as slave labour for the Japanese.

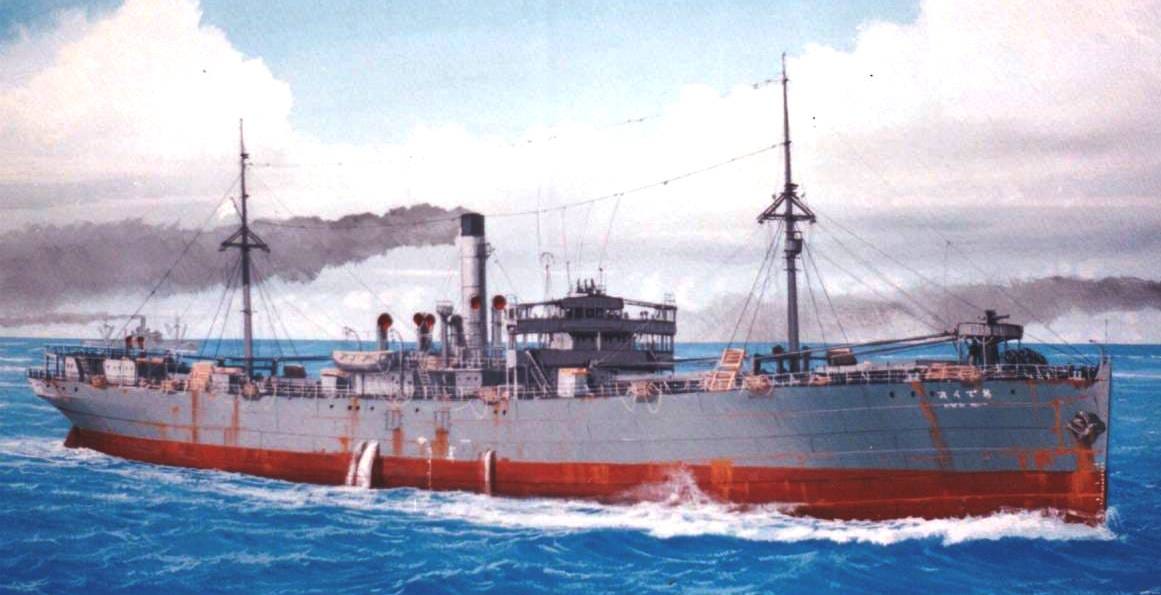

On the 25th October, at the Singapore dockside, Titherington1 and around a thousand other PoWs had been loaded aboard the England Maru, an old freighter with the most basic facilities. They were to spend most of the journey in the bare hold:

We were not allowed on deck until the ship was well out to sea, and then only for 15 minutes. This was the routine during the next few weeks, just a quarter of an hour each day in the fresh air, the rest of the day being spent consigned to the stinking holds below.

Part of this small but invaluable daily break on deck could be used to visit the very primitive toilets, nothing more than a large box arrangement with a hole in the base, the whole thing being suspended over the side ofthe ship. Without a doubt it was the most frightening method of going to the toilet imaginable; certainly nothing in my life had ever equipped me for such an experience.

The alternative facilities were buckets in each hold. When the bucket required emptying it had to be lifted out of the hold on the end of a rope. One unsteady pull meant, at best, that the contents were deposited on the floor of the hold. A panic-stricken spell in the box hanging over the side of the ship was preferable to a floor where we lived that was strewn with faeces.

With my shoulder against a bulkhead, and one leg braced against an upright to counter the rolling of the ship, I sat eating one of our twice daily portions of boiled rice, while at the same time watching a man who was obviously in the throes of dysentery.

For the next few days the ship battered its way through the South China Sea, pitching and rolling in a most alarming way. We listened to the ancient plates and timbers creaking around us and, at times, mused on the irony that this vessel in which we were travelling to an unknown destination had been built, many years before, on the banks of the Clyde.

At times the stench was almost overpowering, and to add to the general misery more and more men were going down with dysentery.

It was during this voyage I really learned to overcome any squeamishness I might still have had. With my shoulder against a bulkhead, and one leg braced against an upright to counter the rolling of the ship, I sat eating one of our twice daily portions of boiled rice, while at the same time watching a man who was obviously in the throes of dysentery.

With his backside on a latrine bucket he was vomiting from his other end into a container, and quite often missing it. With the next roll of the ship he pitched forward, spilling the contents of both containers, and went crashing down on the deck. I put down my rice, wiped up the spillage as best as I could, helped him back onto the bucket and returned to my meal. My sensibilities had been brought to a point of complete numbness.

The paucity of the rations took on a new dimension on board ship but in a sense the obsession over food began to lessen; there were now other problems to concern ourselves with: illness, sea sickness and the future.

I was, at the time, like other men to whom I spoke, prepared to accept the acute shortage of food as a temporary situation. There were, after all, over 1,000 prisoners on board plus a hundred japanese troops, and the ship’s crew. It was a small vessel and rations were bound to be scarce. The problem, I reasoned, would end when we arrived at our destination.

The one thing that never entered my head was that our future was to be one of sheer starvation, in far too many cases resulting in death.

In his memoir Titherington recalls that he was actually quite ‘lucky’ to be on the England Maru. Many other Japanese prisoner transports, being unmarked enemy vessels, were torpedoed. The Montevideo Maru was the first but there were many others.

Arthur Titherington wanted to ensure that these ships, sometimes known as the 'Hell Ships', were not forgotten:

Monteviedo Maru. Sunk by submarine 1 July 1942. Total number of prisoners on board 1,053.

No survivors.

Kachidoki Maru. Torpedoed by aircraft 12 September 1942. Total number of prisoners on board 950. Missing or dead 435.

Tyofuku Maru. Sunk by aircraft 21 September 1942. Total number of prisoners on board 1,287. Missing or dead 907.

Lisbon Maru. Sunk by submarine 2 October 1942. Total number of prisoners on board 1,816. Missing or dead 839.

Nichimei Maru. Sunk by submarine 15 January 1943. Total number of prisoners on board 548.

No survivors

Suez Maru. Sunk by torpedo 29 September 1943. Total number of prisoners on board 548.

No survivors.

Tamabuko Maru. Sunk by torpedo 24 June 1944. Total number of prisoners on board 772. Missing or dead 560.

Haragiku Maru. Sunk by torpedo 26 June 1944. Total number of prisoners on board 720, Missing or dead 177.

Rakuyo Maru. Sunk by torpedo 12 September 1944. Total number of prisoners on board 1,214. Missing or dead 1,179.

Shinyu Maru. Sunk by submarine 17 September 1944. Total number of prisoners 750.

No survivors.

Unya Maru. Sunk by submarine 18 September 1944. Total number of prisoners on board 2,200. Missing or dead 1,477.

Arizan Maru. Sunk by torpedo 24 October 1944. Total number ofprisoners on board 1,782. Missing or dead 1,778.

Oryoku Maru; Enoura Maru; Brazil Maru. Torpedoed by aircraft 9 January 1945. Total number of prisoners on board the three ships 1,620. Missing or dead 1,060.

Arthur Titherington: Kinkaseki: One Day at a Time

Arthur Titherington died in 2010, see Telegraph obituary, having spent the greater part of his life trying to get some form of justice from the Japanese for their treatment of Prisoners of War.