The Fleet Air Arm and the War in Europe 1939-1945

A newly published history of Royal Navy aviation in the war

12th February marked the anniversary of the ‘Channel Dash’ and my post drew heavily on David Hobbs’ account of the action in his recently published The Fleet Air Arm and the War in Europe 1939-1945. This is a new history by a former Royal Navy Commander who has established himself as a naval historian in recent years.

The Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm played a crucial role in so many significant actions during the war. Hobbs has already written about their role in the Mediterranean and the Pacific during the war, so this volume completes the picture.

Once again he has produced a highly readable account that places Royal Naval air operations in their proper context - technical, tactical and strategic - without neglecting the human story. A series of challenging episodes - Norway, Bismarck, the convoy battles, Tirpitz - have been thoroughly researched from a variety of sources. An excellent narrative history that will be a must read for naval aviation enthusiasts but also appreciated by a wider audience.

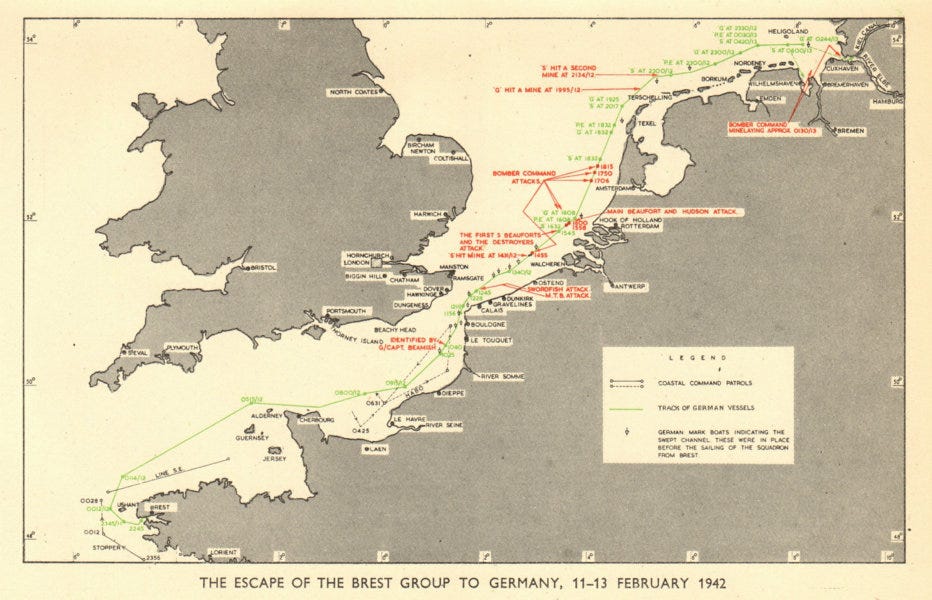

The following excerpt provides a bit more of the story of the Channel Dash, taking up the story some 11 hours after the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen had sailed:

Plots from radar stations manned by the RAF across the south-east coast of the UK fed their information into the Fighter Command filter room at Stanmore. By 0825 one of these plots was actually tracking the German warships’ air escort as they made their way up-Channel but it was assessed by the senior controller as enemy aircraft escorting a coastal convoy. No one thought to ask what kind of coastal convoy would be worthy of such a large air escort and no one seemed to have been briefed about Fuller.

A number of stations reported interference on their radar screens but these were thought to be caused by atmospherics; there had, after all, been similar degradation that had got worse over the previous days. Radar jamming would, logically, have been a significant element of any German break-out plan but when it happened no one in Fighter Command recognised it for what it was and, again, no report was passed up the chain of command.

A backstop had been built into the surveillance structure as insurance against the German squadron slipping through the ASV radar patrols undetected. Every day Fighter Command sent out a fighter reconnaissance to carry out a visual search of the Channel between the mouth of the Somme and Ostend. This had been routine for some months but Fuller gave it an added significance; they were known as ‘Jim Crow’ patrols and if they saw anything an anti-shipping strike was to be organised.

Admiral Ramsay was only informed if it was thought that the vessels detected might be suitable for attack by MTBs. The fatal flaw in the ‘Jim Crow’ procedure was that the pilots were briefed, in accordance with 11 Group instructions, not to make radio transmissions except in an emergency. However, there was no explanation of what constituted an emergency and Fuller was not mentioned.

On that fateful morning what greater emergency could there have been in the Channel than the location of the German squadron on which the Fuller plans had been so carefully made? At 0845 two ‘Jim Crow’ Spitfires took off from RAF Hawkinge and when they returned they mentioned that they had seen a considerable number of E-boat movements. These were reinforcements that had sailed to join the German squadron as it made the transit of the Straits of Dover but they were not recognised for what they were.

By 0925 the filter room at Stanmore was receiving a growing number of reports about what it still assessed to be a coastal convoy escorted by aircraft, despite the fact that it was moving up Channel in excess of 20 knots. Fighter Command decided that a shipping strike might be necessary and ordered a second ‘Jim Crow’ patrol to investigate and this took off at 1020 from Hawkinge flown by Squadron Leader Oxspring and Sergeant Beaumont.

Meanwhile, a telephone conference was held between Admiral Ramsay, the Admiralty and the three RAF Commands. They decided that there was little chance of the Germans trying to break through the Dover Straits in daylight and the next full alert was set for 0400 on 13 February.

A radar station at Beachy Head was tracking the enemy ships off Boulogne by this stage and tried to telephone Dover on both scrambler and normal telephones but failed to get through. Surprisingly, no one at 11 Group or Fighter Command had thought of passing information about the orbiting aircraft and their supposed high-speed convoy to the Admiralty war room.

At 1033 a third ‘Jim Crow’ Spitfire sortie took off, flown by Group Captain Beamish, Senior Air Staff Officer to Air Vice Marshal Leigh-Mallory of 11 Group with Wing Commander Boyd as his wing man. Beamish had been briefed about Fuller but was apparently only interested in air combat and when the pair saw two enemy fighters off Boulogne they engaged them, losing height rapidly in a turning fight over the Channel.

They came down right over the German squadron and could have reported them immediately to initiate Fuller but, hide-bound by the Fighter Command rule about radio silence, they flew back to their base before reporting what they had seen. At 1040 the Beachy Head radar station managed to telephone its plot information to Portsmouth, from where it was relayed to Dover.

Wing Commander Constable-Roberts, the Air Liaison Officer on Admiral Ramsay’s staff, was informed immediately and, to his credit, he was the first man to recognise what was happening and try to instil a sense of urgency. He telephoned 11 Group to be told that the filter room had been watching this plot for some time and that it was all right. He asked for a further reconnaissance but was told that Oxspring and Beaumont would return shortly having completed their sortie without breaking radio silence.

During their debrief at Hawkinge after 1050 these pilots described seeing ‘about thirty or forty enemy ships escorted by five destroyers or E-boats’. Sergeant Beaumont added that he had seen a ship with a tripod mast but when shown a book of silhouettes he failed to pick out Scharnhorst, Gneisenau or Prinz Eugen. Curiously, his identification was taken as final and when the report was passed to Fighter Command there was no suggestion of executing Fuller, only of organising a shipping strike, known within the Command as a ‘Roadstead’ operation, against an enemy convoy that appeared to be larger than usual.

News that the Command was preparing a Roadstead eventually reached Admiral Ramsay’s staff at 1105 but there was no mention of big warships or even one with a tripod mast. Constable-Roberts became even more suspicious and, although Admiral Ramsay was sceptical about the possibility of the enemy risking a passage of the Straits in daylight and was inclined to wait for further evidence, his air liaison officer persuaded him approve a telephone call to Manston in which he warned Esmonde ‘to get his chaps ready’.

Esmonde’s immediate response was to ask if he should have his torpedoes set to run deep and Constable-Roberts advised him to do so as there would be no time when he gave the word to go. At 1109, thirty minutes after he had identified the German battlecruisers, Group Captain Beamish landed and reported what had seen.

Although Beamish and his wing man had not specifically been part of the Fuller search plan, both were senior officers who should have realised the importance of what they had seen and radioed their information before flying back. They had actually been in combat with enemy fighters so what on earth was the point of trying to hide their presence over the Channel with radio silence?

At 1125 confirmation that the German ships were about to pass through the Straits of Dover was finally telephoned to Dover by the Admiralty war room.

This excerpt fromThe Fleet Air Arm and the War in Europe 1939-1945 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

The above images are not from this book - it does have a good selection of contemporary images and maps but they do not reproduce well here.