The 'Channel Dash'

12 February 1942: Extraordinary heroism cannot compensate for a catalogue of errors that lets German warships pass under the noses of the British

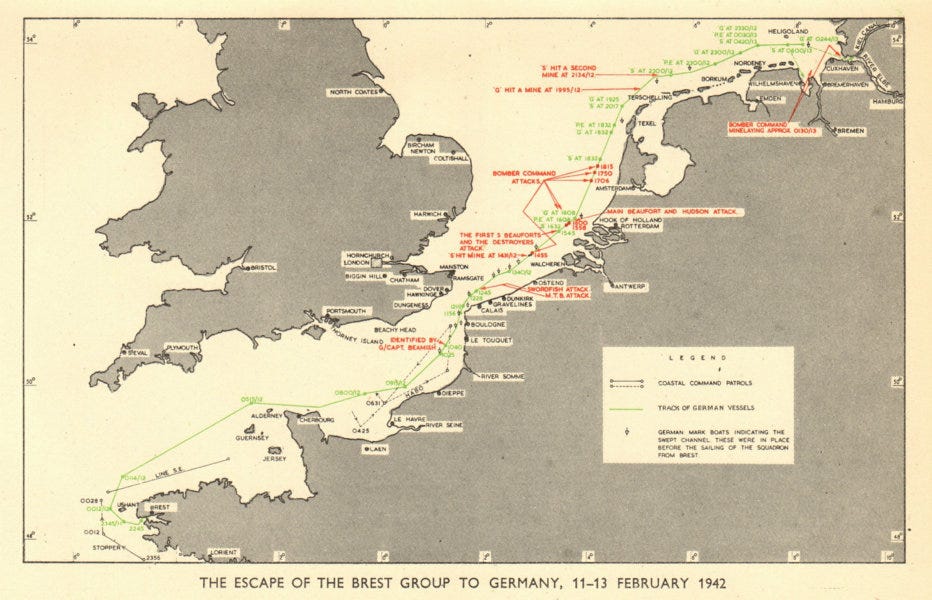

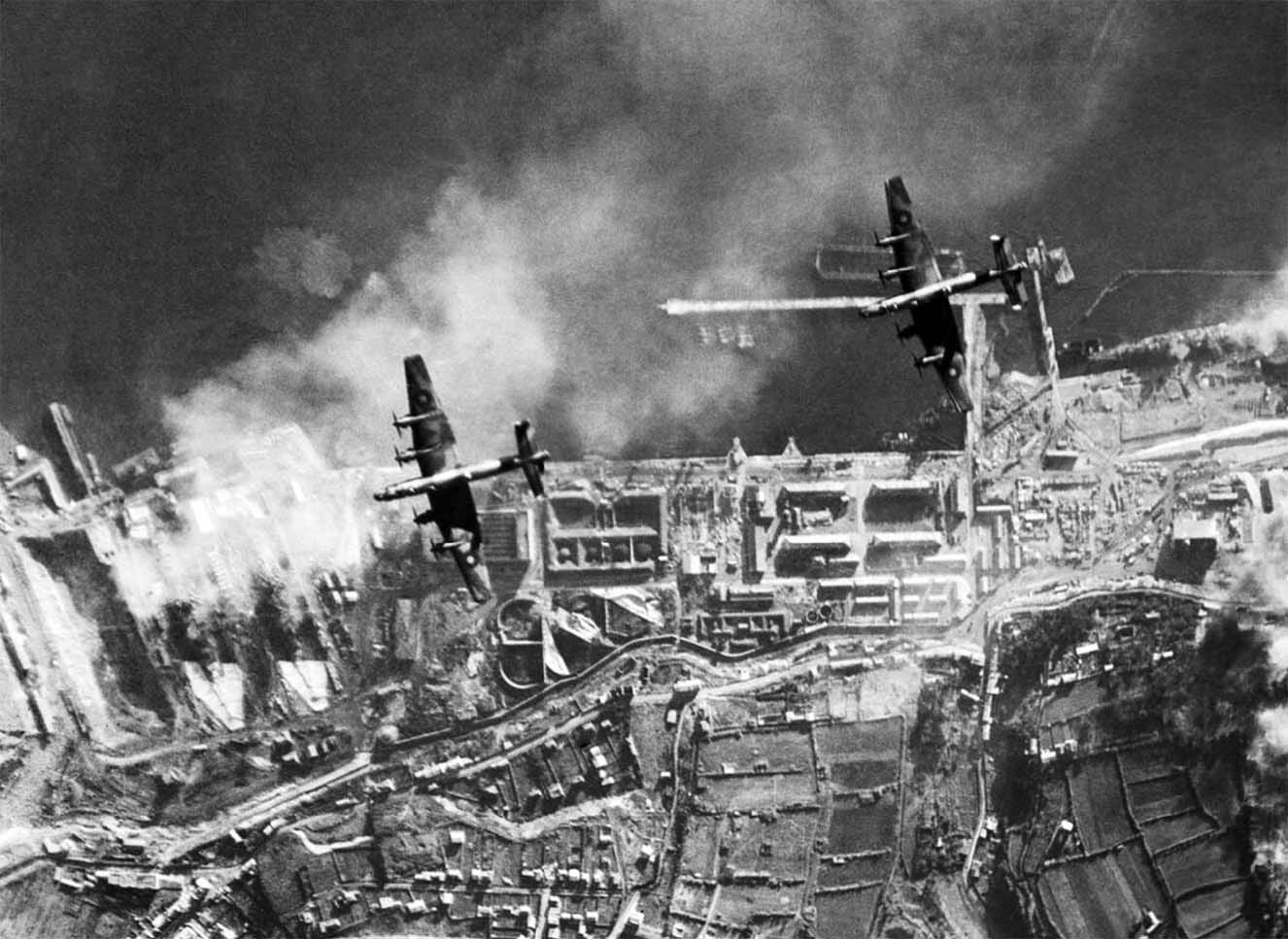

The Channel Dash, as it has become known (officially designated Operation Cerberus by the Germans), took place when the Germans sought to take the two ‘pocket battleships’ Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the battle cruiser Prinz Eugen from the French port of Brest back to the safety of German ports. In Brest they threatened British convoys - but in practice they had been cooped up under almost constant attack by the RAF since January 1941.

The move had been keenly anticipated by the British - and detailed plans of attack were drawn up under Operation Fuller. Unfortunately disparate levels of engagement with the plan between the RAF and the Royal Navy led to a series of failures in preparedness1.

The RAF Coastal Command airborne surveillance that should have triggered the plan failed to detect the German ships until they were halfway up the Channel. The 300 RAF Bomber Command aircraft that were intended as the principal attack force were not kept at the level of readiness expected and could not be used in a coordinated attack. The various RAF Fighter Command squadrons were not properly briefed on the importance of their role in providing protection to both aircraft and naval torpedo attacks.

The extraordinary firepower of the planes of RAF and the ships of the Royal Navy was whittled down to one of the back up plans - just six Swordfish bi-planes from the Fleet Air Arm became the cutting edge of the attack. Although they appeared ancient they could be a potent force - as had been demonstrated in the attacks on the Bismarck.

825 Naval Air Squadron had lost all their Swordfish aircraft in the sinking of HMS Ark Royal but had been re-equipped and were based at RAF Manston in Kent. The plan was that they would make a direct head on ‘fan attack’ on the ships as they approached the narrowest point in the Channel. With torpedoes released from different directions simultaneously it would be impossible for the ships to evade them.

The plan required advance notice so that they could attack from head on. They also needed strong RAF fighter cover to protect them as they made their run in. Neither element materialised.

Lt Cdr Eugene Esmonde was forced to improvise a new plan at the last minute as he discovered that the ships were steaming away from him. They had already passed the Straits of Dover. He was on the telephone trying to coordinate the RAF fighter cover until the last minute - when he realised he had no time left if he was to catch up with the German ships.

Despite that lack of fighter cover, Lt Cdr Eugene Esmonde led his sluggish biplanes to try to catch up with their target. Weighed down by their torpedoes they had an air speed of around 90 knots. The three German ships, now speeding away from them at up to 27 knots, were each bristling with anti-aircraft guns and there were an estimated 300 Luftwaffe planes assigned to protect them.

The six planes of 825 Squadron did not return. Although some got torpedoes away, none hit the ships, all the Swordfish were downed and only five of the 18 crew were rescued.

Esmonde was not among them; he received a posthumous Victoria Cross:

The six Swordfish took off at 1220 and set course for the enemy, accompanied by only one of the five Fighter Squadrons arranged to escort him. After ten minutes flight his small force was heavily attacked by Messerschmitts and F.W. 190's; despite these attacks, which had inflicted some damage on all his aircraft and separated him from his fighter escort, he flew on undeterred.

‘He then encountered a withering anti-aircraft fire, which shot saw most of his port wing, but was observed to regain control of his aircraft , straighten up and fly on steadily towards the battle cruisers.’

He then encountered a withering anti-aircraft fire, which shot saw most of his port wing, but was observed to regain control of his aircraft , straighten up and fly on steadily towards the battle cruisers. In this manner he led the whole of his formation over the enemy destroyer screen into a position where they could launch their torpedoes. He was then seen to be attacked and shot down by an enemy fighter and his aircraft crashed into the sea.

His most conspicuous bravery, extreme devotion to duty and supreme self sacrifices inspired the remainder of his gallant flight to continue and rendered possible an attack from which none retuned and which resulted in one of the German battle cruisers being hit by at least one torpedo. Such bravery as was his is in keeping with the highest naval traditions and will remain through generations to come a stirring memory.

Captain Hoffmann of the Scharnhorst:

Poor fellows. They are so very slow. It is nothing but suicide for them to fly against these big ships.

Willhelm Wolf, also on the Scharnhorst:

What an heroic stage for them to meet their end on. Behind them their homeland which they had just left with their hearts steeled to their purpose still in view.

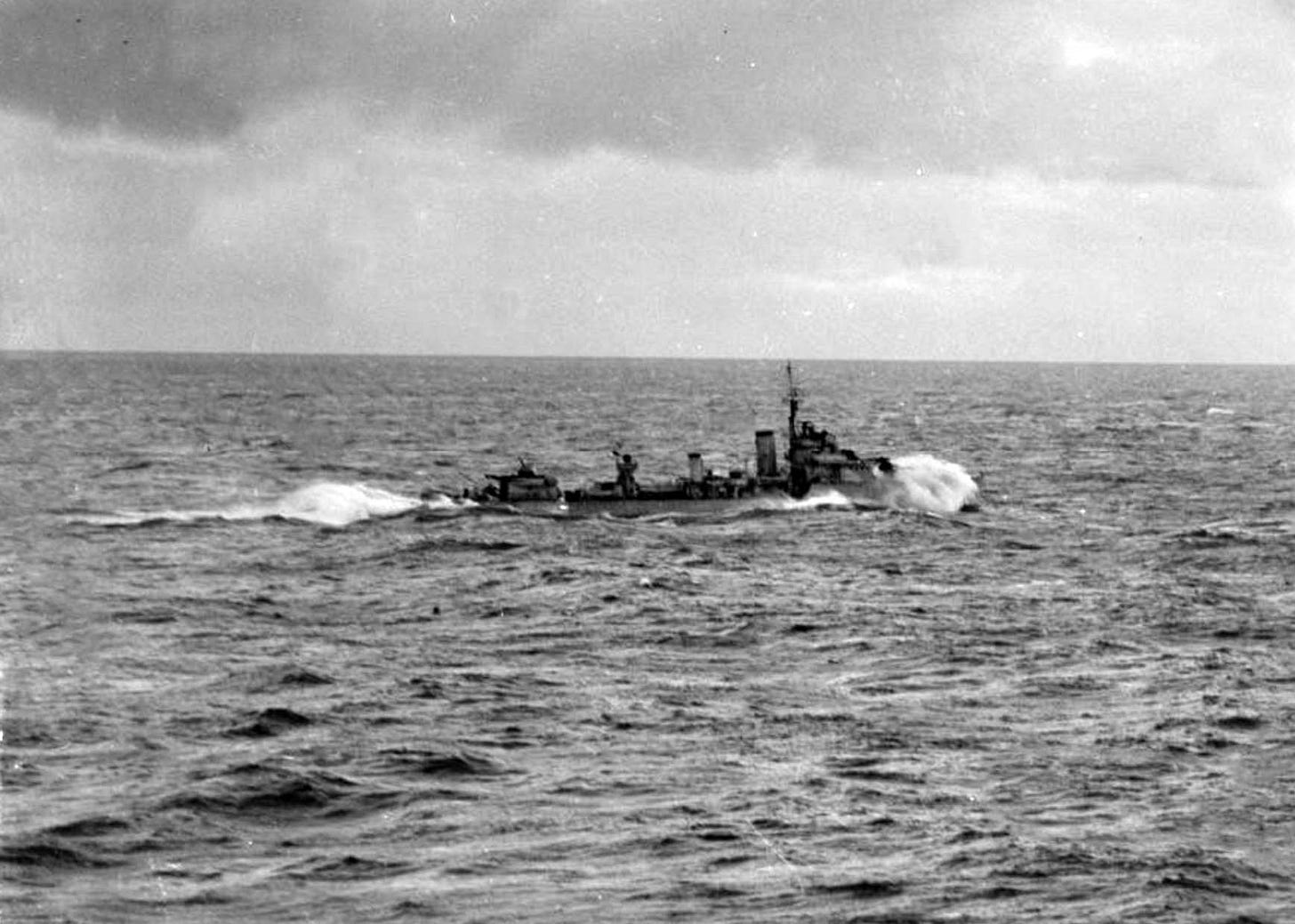

A further valiant torpedo attack was made by Royal Navy destroyers without success. German aircraft mistook them for part of the German naval escort but they were subjected to attack by RAF bombers and torpedo planes as well as fire from the Battleships. Twenty-three men died when HMS Worcester was hit2.

Only 39 of the 242 RAF bombers despatched found their target and dropped bombs near the German ships - none hit.

All was not lost however. As they moved into the North Sea both the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were damaged by mines that had been dropped a few days earlier by RAF Bomber Command. The low status ‘Gardening’ operations, often given to new bomber crews, were of more value than might have been expected.

For a thorough survey of the catalogue of errors and mis-communications during Operation Fuller see David Hobbs: The Fleet Air Arm and the War in Europe 1939-1945 published 2022.

For an account see The Channel Dash Association