The Battle of Los Angeles

25th February 1942: US Army anti-aircraft batteries open a barrage of fire at possible Japanese planes believed to be about to attack Los Angeles

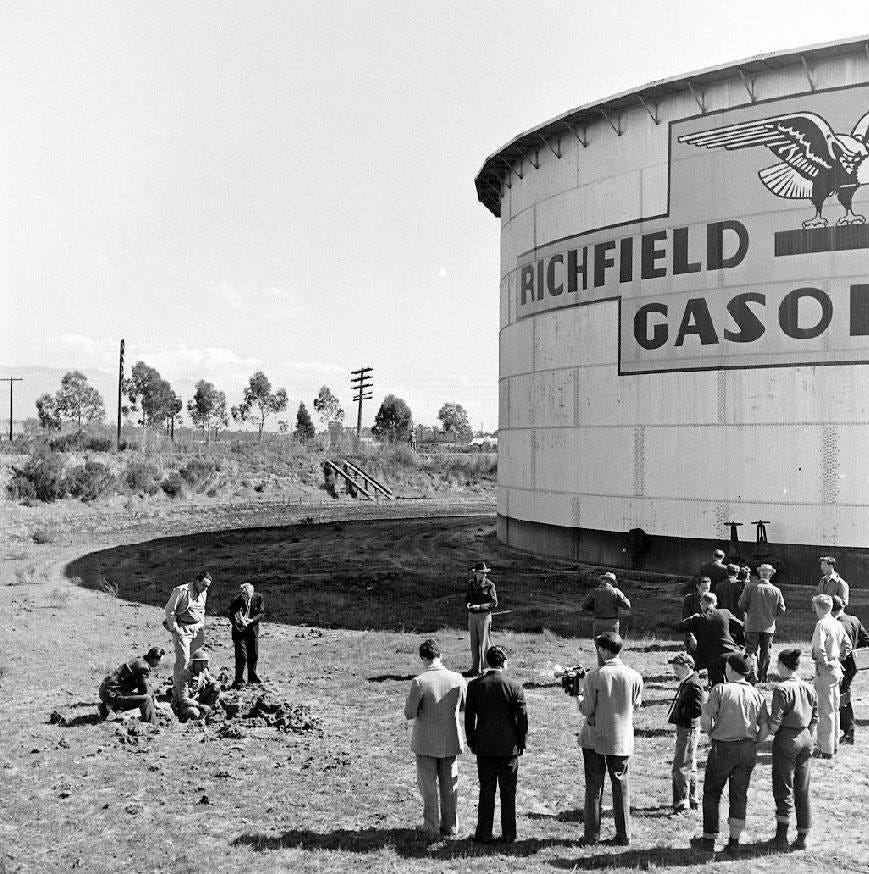

On the 23rd February the mainland of the United States came under direct attack for the first time in the war. A Japanese submarine briefly surfaced and fired around thirteen shells onto the Oil Refinery at Ellwood, Santa Barbara on the Californian coast. Little damage was done - none of the shells hit any vital part of the installation1- the total cost of the damage was estimated at about $500.

Inevitably the attack led to speculation that a more serious Japanese attack, possibly even an invasion, was imminent and tension rose on the west coast. This atmosphere may account for the events on the 25th. These are best described by the most comprehensive official account2:

During the night of 24/25 February 1942, unidentified objects caused a succession of alerts in southern California. On the 24th, a warning issued by naval intelligence indicated that an attack could be expected within the next ten hours. That evening a large number of flares and blinking lights were reported from the vicinity of defense plants. An alert called at 1918 [7:18 p.m., Pacific time] was lifted at 2223, and the tension temporarily relaxed.

But early in the morning of the 25th renewed activity began. Radars picked up an unidentified target 120 miles west of Los Angeles. Anti-aircraft batteries were alerted at 0215 and were put on Green Alert - ready to fire - a few minutes later. The AAF kept its pursuit planes on the ground, preferring to await indications of the scale and direction of any attack before committing its limited fighter force.

Radars tracked the approaching target to within a few miles of the coast, and at 0221 the regional controller ordered a blackout.Thereafter the information center was flooded with reports of "enemy planes" even though the mysterious object tracked in from the sea seems to have vanished. At 0243, planes were reported near Long Beach, and a few minutes later a coast artillery colonel spotted "about 25 planes at 12,000 feet" over Los Angeles.

At 0306 a balloon carrying a red flare was seen over Santa Monica and four batteries of anti-aircraft artillery opened fire, whereupon "the air over Los Angeles erupted like a volcano." From this point on reports were hopelessly at variance.

"swarms" of planes … of all possible sizes, numbering from one to several hundred, traveling at altitudes which ranged from a few thousand feet to more than 20,000 and flying at speeds which were said to have varied from "very slow" to over 200 miles per hour, were observed to parade across the skies.

Probably much of the confusion came from the fact that anti-aircraft shell bursts, caught by the searchlights, were themselves mistaken for enemy planes.

In any case, the next three hours produced some of the most imaginative reporting of the war: "swarms" of planes (or, sometimes, balloons) of all possible sizes, numbering from one to several hundred, traveling at altitudes which ranged from a few thousand feet to more than 20,000 and flying at speeds which were said to have varied from "very slow" to over 200 miles per hour, were observed to parade across the skies.

These mysterious forces dropped no bombs and, despite the fact that 1,440 rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition were directed against them, suffered no losses. There were reports, to be sure, that four enemy planes had been shot down, and one was supposed to have landed in flames at a Hollywood intersection.

Residents in a forty-mile arc along the coast watched from hills or rooftops as the play of guns and searchlights provided the first real drama of the war for citizens of the mainland.The dawn, which ended the shooting and the fantasy, also proved that the only damage which resulted to the city was such as had been caused by the excitement (there was at least one death from heart failure), by traffic accidents in the blacked-out streets, or by shell fragments from the artillery barrage.

There had been no attack by the Japanese. The whole episode was an embarrassing illustration of how the mere anticipation of attack could produce a real response. Once one battery of guns began firing at a perceived target others joined in and the incident escalated out of control.

The official response did not help to re-assure people. Different interpretations of what had happened were presented by the Navy and the Air Force. The New York Times on 28 February suggested that the more the incident was studied, the more incredible it became:

If the batteries were firing on nothing at all, as Secretary Knox implies, it is a sign of expensive incompetence and jitters.

If the batteries were firing on real planes, some of them as low as 9,000 feet, as Secretary Stimson declares, why were they completely ineffective? Why did no American planes go up to engage them, or even to identify them?

…

What would have happened if this had been a real air raid?

The episode may have had a personal dimension - as the Japanese commander of the I-17 submarine, Kozo Nishino, had been humiliated when he fell over into some cactuses on a pre-war visit to the refinery for refuelling - according to the California State Military Museum. Although others have disputed this as myth.

The Army Air Forces in World War II: Defense of the Western Hemisphere. 1. Washington, D.C: Office of Air Force History. pp. 277–286. ISBN 9780912799032.