'On The Eastern Front At Seventeen'

An excerpt from a newly translated memoir of a Red Army soldier who just managed to survive the German attack into the Caucasus in August 1942

Just translated and published in English for the first time is On The Eastern Front At Seventeen. This is a fresh and immediate memoir of the experiences of a young man suddenly thrust into service with the Red Army. With no military training he very soon experiences the ruthlessness of Soviet discipline, the horrors of combat - where so many of his comrades were killed only days after joining up - and appalling treatment as a POW of the Germans. He managed to escape and vividly describes life in the Red Army up to 1944 when he was wounded.

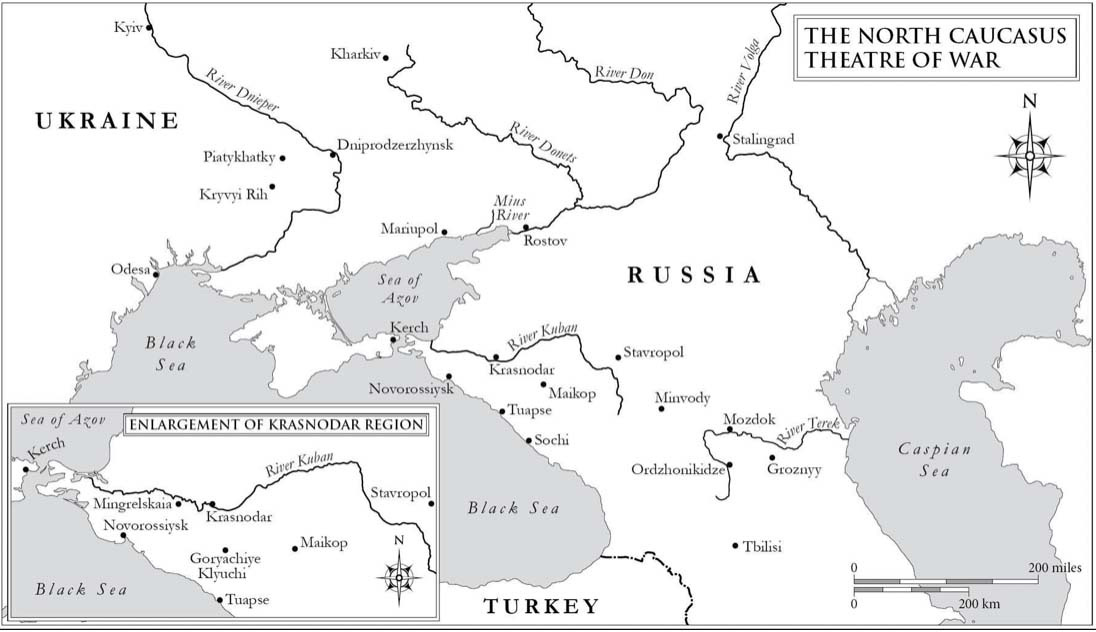

Sergey Drobyazko lived in the city of Krasnodar on the banks of the Kuban river in the northern Caucasus. He had just left school and was working in a weapons factory in August 1942 when it became apparent that the German offensive of 1942 was headed their way. His generation of young men were all ‘volunteered’ into the Red Army, provided with weapons and immediately marched off towards the front.

After coming under air burst artillery fire for the first time they retreated in some disorder …

The following morning it turned out that we were not far from a village of the Adygei ethnic minority. The houses themselves were almost hidden by a field of tall maize. The officers checked on the personnel and weapons.

It turned out that in the other companies a few rifles had been lost. We were lined up in a forest clearing beyond the village. A group of top brass appeared with bars on their tabs. Some had stars sewn onto their sleeves, indicating they were political education officers.

To one side of us a section of sub-machine gunners was lined up - seemingly elite Red Army troops in well-fitting uniforms.

Commands rang out and in the ensuing silence we were read an order from the People’s Commissar for Defence, Comrade Stalin, who was known for many years thereafter as ‘Not-a-Step-Back’1. The order provided for harsh measures against panic merchants, deserters and saboteurs. With this aim in mind, blocking detachments were being formed from special military units, which would operate behind the active fighting units and were charged with preventing retreats by force of arms.

Following the reading of the order, the general situation on the various fronts was explained and it was announced that the Kuban River was the line which the enemy must not be allowed to cross. In this endeavour we would be assisted by other military units supported by artillery and air forces.

After this, three lads were marched out into the clearing under guard. Something that was not quite a command and not quite a tribunal verdict was read out to the effect that, for losing their weapons, they were sentenced to death by firing squad.

We gazed at the lads standing in front of us, who, to judge by their calm behaviour, did not appear to understand properly what was going on. On command they turned about, marched 40 paces away from us, out of step, and again stood facing us. At the same time a squad of sub-machine gunners lined up between us and the lads.

We were all waiting for those condemned to be told how badly they had behaved and given a final warning that they must acknowledge their guilt and not repeat such behaviour. We expected them to be given a good telling-off and let go, as had happened to us before at school or at home. That is most likely what the three lads facing us hoped. But suddenly on command short bursts of fire rang out and, before our very eyes, the three lads, who had been marching amongst us only yesterday, fell slowly onto the grass.

With these shots it seemed as if the bright morning sunshine had darkened. It is difficult to describe the dejected state of mind which gripped us. ‘Just for losing their weapons!’

We spent the rest of the day in the small wood. There was none of the usual chatter and the occasional conversations were conducted in hushed voices. The events of the morning had done nothing for our fighting spirit; on the contrary, our morale was appalling. Was this cruelty necessary and justified?

Of course, there was a lot I didn’t know then and I could not imagine the whole extent of the tragedy facing our country. The fates of ordinary individuals meant nothing in wartime, and their lives were worth nothing compared to the huge and irreplaceable total losses. The most brutal measures were taken for the sake of the country’s defence, for its salvation - everything possible and impossible to strengthen resistance to the enemy.

Later I became accustomed to a situation whereby all difficulties, privations, acts of brutality, losses, even various absurdities, were explained away by a single phrase: ‘the war’.

Dedicated to the lads who perished at the Pashkovskaia crossing in August 1942.

My sister once told me: ‘This is now of no interest to anyone except you yourself.’

This excerpt from On The Eastern Front At Seventeen appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.