Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong

5th March 1942: The British government begins to piece together the activities of the Japanese Army following the surrender of Hong on Christmas Day 1941

Hong Kong had been captured by the Japanese on Christmas Day 1941, after an eighteen day battle. As in Singapore some troops and civilians had been able to escape by boat in the last hours - and their stories had now been collated. On the 5th March 1942 the British war cabinet discussed a Foreign Office paper regarding the treatment of prisoners of war and civilians in Hong Kong.

The public release of this information was no comfort to those who knew that their loved ones had been in Hong Hong at the time of the Japanese invasion.

This included a draft statement to be made to Parliament1:

His Majesty's Government are now in possession of statements by reliable witnesses who succeeded in escaping from Hong Kong. Their testimony establishes the fact that the Japanese Army at Hong Kong perpetrated against their helpless military prisoners and the civil population, without distinction of race or colour, the same kind of barbarities which arouse the horror of the civilised world at the time of the Hanking massacre of 1937.

It is known that fifty officers and men were bound hand and foot and then bayonetted to death. It is known that ten days after the capitulation wounded were still being collected from the hills and the Japanese were refusing permission to bury the dead. It is known that women, both Asiatic and European, were raped and murdered and that one entire Chinese district was declared a brothel regardless of the status of the inhabitants.

All the survivors of the garrison, British, Indian, Chinese and Portuguese have been herded info a camp consisting of wrecked huts without doors, windows, light or sanitation. By the end of January 150 cases of dysentery had occurred in the camp but no drugs or medical facilities were supplied. The dead had to be buried in a comer of the camp.

‘The Japanese claim that their forces are animated by a lofty code of chivalry, Bushido, is a nauseating hypocrisy. That is the first thing. The second is that the enemy must be utterly defeated.’

The Japanese guards are utterly callous and the repeated requests of General Maltby, the General Officer Commanding, for an interview with the Japanese commander have been curtly refused. This presumably means that the Japanese high command have connived at the conduct of their forces.

The Japanese Government stated at the end of February that the numbers of prisoners in Hong Kong were British 5,072, Canadian 1,689, Indian 3,829, Others 357, Total 10, 947.

Most of the European residents, including some who are seriously ill, have been interned and, like the military prisoners, are being given only a little rice and water and occasional scraps of other food.

The Japanese Government have refused their consent to the visit to Hong Kong of a representative either of the Protecting Power or of the International Red Cross Committee. They have in fact announced that they require all foreign consuls to withdraw from all the territories they have invaded since the outbreak of war. It is clear that their treatment of prisoners and civilians will not bear independent investigation.

I have no information as to the conditions of our prisoners of war and civilians in Malaya. The only report available is a statement by the Japanese official news agency of the 3rd March stating that 77,699 Chinese have been arrested and subjected to what is described as "a severe examination". It is not difficult to imagine what that entails.

I am sorry that I have had to make such a statement to the House. Two things will be clear from it, to the House, to the country and to the world. The Japanese claim that their forces are animated by a lofty code of chivalry, Bushido, is a nauseating hypocrisy. That is the first thing. The second is that the enemy must be utterly defeated.

The House will agree with me that we can best express our sympathy with the victims of these appalling outrages by redoubling our efforts to ensure his utter and overwhelming defeat.

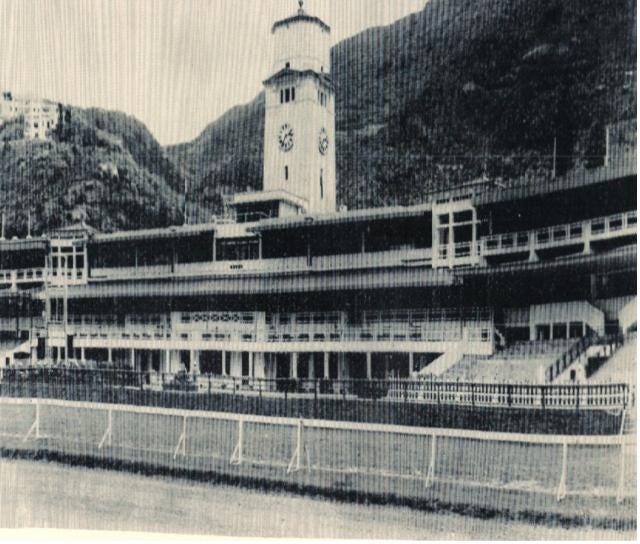

After the war there were many more eye witness accounts, some used for war crimes trials. Barbara Redwood2 described an incident at the Jockey Club where a number of volunteer nurses were sheltering after the surrender:

[O]ur place was pushed open. There stood a group of Japanese soldiers. The one who held the torch (which had a beam like a car headlight) flashed around, showing us all huddled beneath our blankets. They advanced.

"Get up all" one commanded. We in the beds all scrambled out. Rather undignified we must have looked, as climbing out of a camp bed by the end, could not be done with dignity...

They scrutinized each one in turn, almost blinding us as they shone the torch in our faces one by one. It was a terrible ordeal, as we did not know what was to happen, and when they selected about four, we feared the worst.

As they selected each one the spokesman said "Go Jap. No come kill all." Then turning to the rest he said "Sleep," and we again climbed to our beds. They went away, taking the girls with them ... I could not say how long it was before we heard running light footsteps, and one of the girls rushed in sobbing.

Very soon the others followed, and almost before we could get them quieted, the torch reappeared… they looked under the table, and found those who had taken refuge there.

They made them come out and ordered some of them to go with them. The same threat, "No come kill all."

The statement was approved by the War cabinet and made to the House of Lords on 10th March 1942, see TNA CAB 66/22/41.

IWM, London, Item PP/MCR/25, Memoirs of Mrs. M. W. (Barbara) Redwood, "Incident at Jockey Club, Happy Valley, Hong Kong, Dec. '41,

For a comprehensive survey see: Charles G. Roland: Long Night’s Journey into Day: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-1945