'Infantry Warfare'

A Photographic History of Infantry Warfare 1939-1945

A Photographic History of Infantry Warfare 1939-1945, first published in 2021, is a highly illustrated survey of all aspects of the infantry role in World War II. It covers all the main theatres and all the principal armies, encompassing everything from uniforms, weapons and tactics through to morale and casualties.

The authors draw on a wealth of material to present this fascinating overview. Its a book that many people will enjoy dipping into as there are more than 400 photographs and illustrations, each making a point, all with explanatory captions. But is also supported by a knowledgeable text. Many people interested in the war will know something of the story told here - but most will learn something new.

The following excerpts are from a longer chapter that considers infantry action in three different extreme environments - the Desert of North Africa, the Jungle and in the Russian Winter.

Desert Warfare

In the desert interior about 10 km from the coast, the vibration of the air makes accurate observation over 1km practically impossible. The light shimmers and plays tricks.

Mirages often looking like sheets of water appear and all contours become blurred, with only a few elevations standing out like islands.

Infantry in the desert are constantly exposed to the effects of sand and dust, in the long columns that transport them to combat as well as in battle itself. Because of the dust thrown up by vehicles, movement on the ground is impossible to conceal and it is difficult to differentiate between friend and foe from the air.

In the day, the problems are sand, dust, heat and searing light; at night, the freezing cold. Sand gets into the works of weapons and engines, making maintenance and protection vital. Distances become difficult to judge in almost featureless terrain.

The desert war was a mechanised war. Mobility was key and thus supply lines and supplies (transported, buried and camouflaged) became even more important factors in planning and maintaining momentum.The interdiction of both sides' resupply convoys - the importance of Malta as a supply base and a centre of air operations, and the British control and use of the Suez Canal were vital factors in the campaign.

Tactically, that trails of the desert were more easily traversed by motor vehicles made it a war of big advances and enveloping movements, but it also made it difficult to hold ground and critical to dig in properly.The danger of enemy tanks breaking through the front made it necessary to develop all-around defensive positions that saw a huge increase in the use of antitank mines. Against motorised or armoured opponents, static troops could only hold their own in elaborately prepared defences - the British called them 'boxes'.

The area suitable for military operations was confined to the relatively narrow strip along the coast and the southern desert zone, both more favourable for rapid movement than the rocky steppe-like north.

All soldiers in the desert were equipped with a pair of dust goggles.There were special air filters (often placed inside) for all motor vehicles, including tanks. In combat, the water consumption was generally so limited that the men even had to go without washing almost entirely. Each man usually received a canteen in the morning filled with coffee or tea, which had to last the whole day.

Normally no water was used to clean vehicles and equipment. However; no great lack of water developed because the fighting was always in the coastal area and in numerous places there were sufficient supplies of fresh water to take care of the basic needs of the troops.

…

Infantry in the Jungle

‘one of the toughest and most extreme environments on earth in which to live and fight - a nightmare of incessant moisture and malevolent insect and reptile life’

From above, tropical and semitropical jungle looks lush, green and beautiful. Up close, in its dense forests, swamps and marshes, it is one of the toughest and most extreme environments on earth in which to live and fight - a nightmare of incessant moisture and malevolent insect and reptile life.

It's all monsoon rains, malarial mosquitoes, snakes and scorpions, ticks that carry lethal scrub typhus and amoebic dysentery leeches that penetrate the tightest clothes to suck blood and lung fly whose vicious bite hardens into a large septic lump. Wounds fester in the heat and take a long time to heal.

Many more casualties arose from the difficult conditions encountered than from the enemy. Such terrain precluded the use of large-scale formations and tended to break up and isolate units, who had to operate alone for long periods, supplied by air drop.

Most jungle fighting takes place at close range, with raids, ambushes, sniping, mines and boobytraps. Evasion, concealment and camouflage become critical. Bases are only tem porary hidden bunkers and tunnels; movement and operations are often carried out at night.This fragmented, guerilla-style warfare called for greater independence among smaller self-contained infantry units that were beefed up with a few extra men and more firepower.

Both in equipment and tactics, the Allies steadily learnt and improved, while the Japanese continued to rely on their close-quarter ferocity and fanaticism, but also operated at night whenever possible. They usually had a squad of about 15 men. It would contain two two-man teams, one for an MG (Type 11,96 or 99), the other a light 50mm mortar; a designated sniper and a rifle grenade launches while the rest of the squad carried Arisaka 6.5mm (later 7.7mm) rifles or Nambu 8mm semi-automatic pistols.

…

The Russian Winter

The German military was not prepared for the pitiless Russian winter They were expecting a quick victory following the invasion of the USSR in June 1941, This failed, with the advances stalled around the outskirts of Moscow by October 1941.

With the loss of two-thirds of their motorised transport there were serious logistical problems getting supplies to the various fronts; one being the supply of warm clothing. Combat in the depths of the Russian winter was brutal, with temperatures falling to -30 or even -40°C, freezing German armour and equipment but, most of all, the soldiers, who had not been properly equipped to fight a winter campaign. Instead they had to wear every item of clothing in as many layers as they could with added coats, blankets and improvised coverings in an attempt to cope.

Soviet kit was prized when they could capture it or loot it from prisoners and corpses. Meanwhile, in the hiatus caused by the cold during the first winter outside Moscow in 1941, fresh Russian divisions came from the Ural Mountains - snow specialists, used to operating in freezing conditions.

For the Red Army frostbite was a punishable offence, as proper winter equipment was officially issued.This consisted of long woollen underpants and vest, a thickly quilted woollen jacket and trousers - telogreikas ('bodywarmers’ with the slang name of vawiks) - a Ushanka faux fur cap with ear flaps, fur-lined mittens with trigger finger slits and Valenki boots made from layers of beaten felt soled in leather or worn with galoshes.There was also a short mid-thigh length suede leather sheepskin and fur-lined coat - the Polushubok - worn by officers. It was warmer than a trenchcoat but not as bulky as the vatnik.

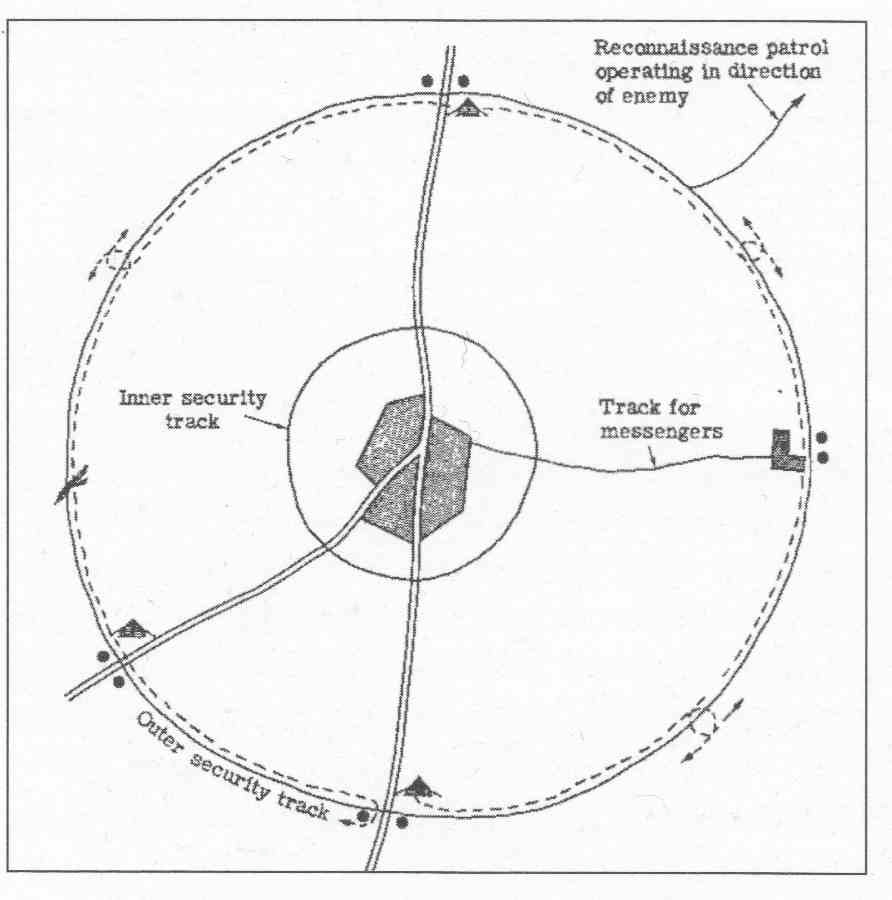

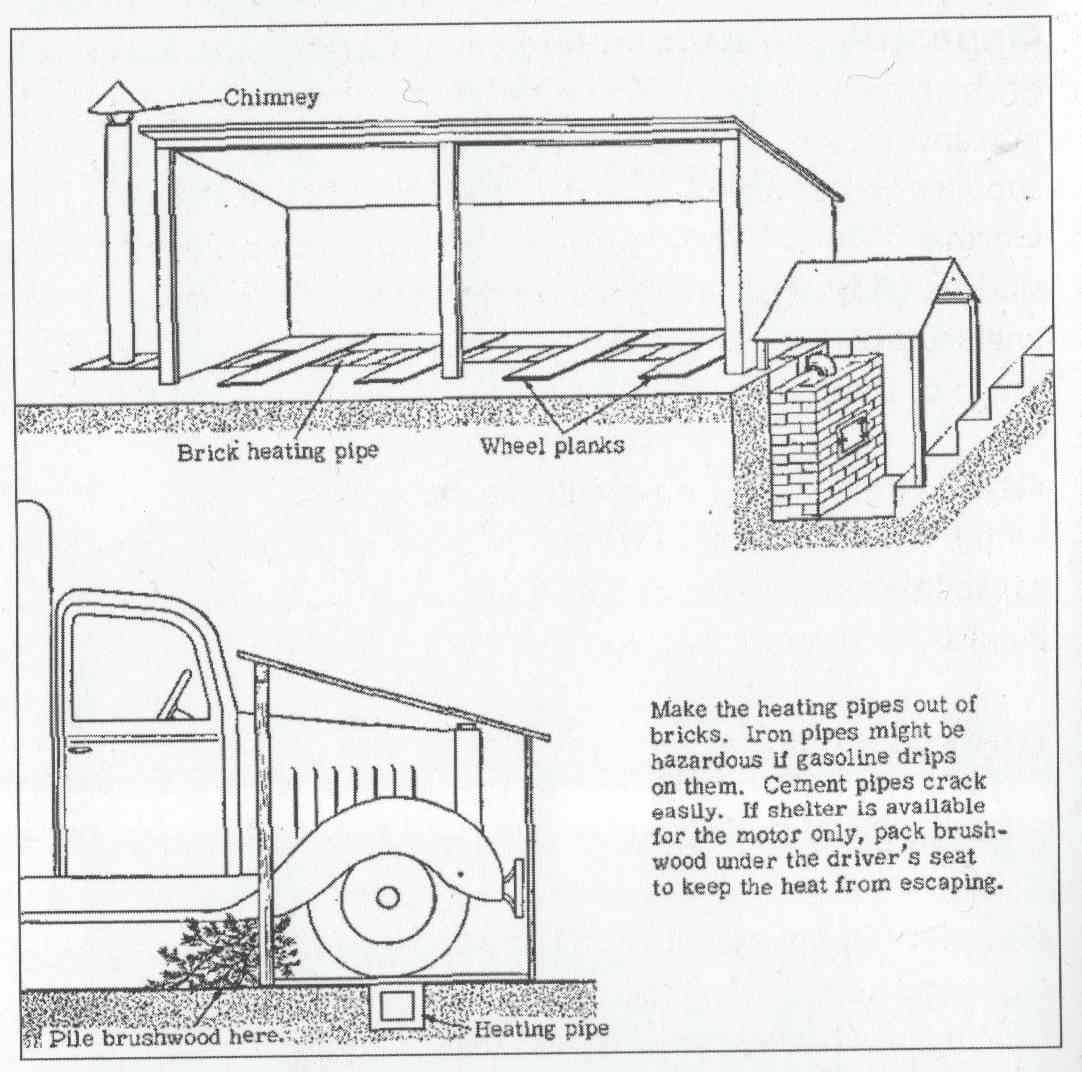

The German Taschenbuch der Winterkrieg (Winter Warfare Manual) was published on 5 August 1942 and was based on the experiences of the first winter of the war in Russia. Essentially it looks at the two vital problems of winter warfare: mobility and shelter. The handbook emphasizes the importance of the systematic preparation and disposition of forces for combat, the need to cut roads and trails and light mobile patrols (if possible, on skis), suggesting that experience has shown that a circular trail around billets and bivouacs is the most effective security measure.

This excerpt from A Photographic History of Infantry Warfare 1939-1945 appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author.