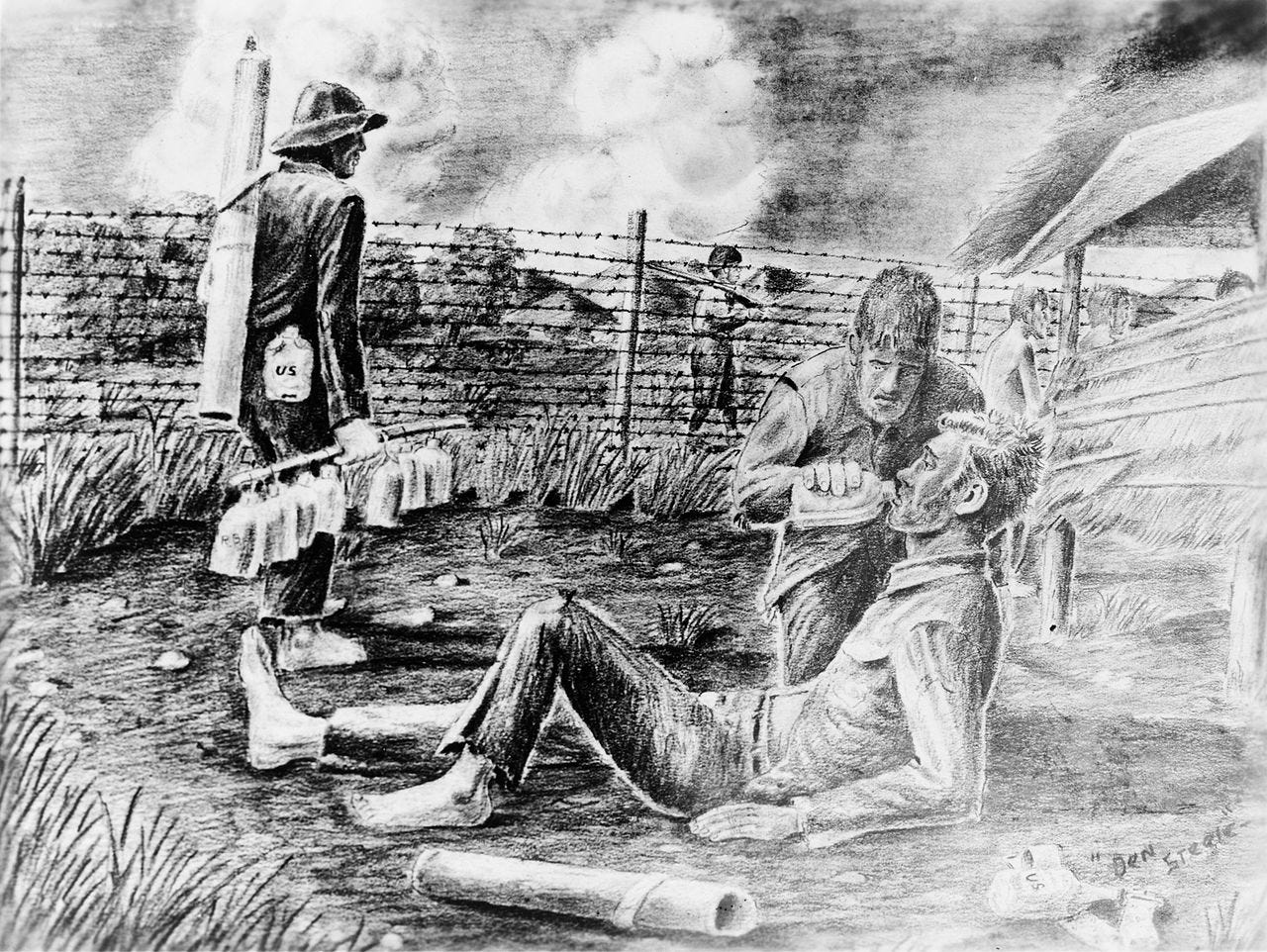

Brutal treatment of US prisoners

21st September 1942: Prisoners of war of the Japanese live in appalling conditions and face torture and death if they attempt to escape

The US troops who had survived the Bataan death march did not fare much better in Cabanatuan prison camp on the Philippines. The whole camp was on a starvation diet and deprived of basic medicine. The death rate was as high as 30 men a day during July 1942 but dropped thereafter ' because the weakest men had died'.

Beatings by the Japanese were commonplace and many serious injuries resulted. There was tremendous incentive to escape but the risks were very high, not only for the escapees but for men who were remained:

the Japs had formed us into "shooting squads" of ten men each, with the threat to kill the other nine if any one man got away.

Commander Melvin H. McCoy, USN, was eventually to escape himself, part of a group of ten men, describes an esape attempt made in September 1942:

This unfortunate attempt was made by two lieutenant colonels and a lieutenant in the Civil Engineer Corps, Navy. I shall not give the names of these men, because I believe their families should be spared the details.

On a very dark night, the two lieutenant colonels and the Naval lieutenant were carrying out a plan to escape by attempting to crawl along a ditch and thereby get through the wire around the camp. Each was carrying a home-made club. They had almost reached their objective when their progress was accidentally halted; an Army enlisted man, said to have been a former Notre Dame football star, stumbled into the three men in the dark.

Whatever his reasons, one of the lieutenant colonels, sprang from the ditch and laid about the enlisted man with his club. Other Americans ran out of their barracks to stop this fray, with the result that it became general and quite noisy. After the actual fighting stopped, the first lieutenant colonel to spring out of the ditch was quite loud in his recriminations, taking the attitude that there had been a deliberate attempt inside the camp to prevent his escape. The enlisted man denied this, and since he was not a member of the officer's "shooting squad", and so would not have suffered from the escape, he presumably was sincere in his denial.

At any rate, the lieutenant colonel used the word "escape" so often that it got to the ears of the Japanese. The three Americans were taken out of the camp, and after some questioning by the Japanese, their punishment was decided upon. The Japanese first beat the three Americans about the feet and calves until they were no longer able to stand. Then they kicked the men and jumped on them with all their weight.

After an extended example of this treatment, the Japanese waited until morning and then stripped the Americans of all their clothing except their shorts. The three men were then marched out into the Cabanatuan road to a point which was in full view of the camp. Their hands were tied behind them, and they were pulled up by ropes from an overhead purchase so that they had to remain standing, but bent forward to ease the pressure on their arms.

Then began forty-eight hours of intermittent torture. Many of the prisoners went into their barracks so they would not be able to see what went on. The Japanese guards were ready with their sub-machine guns in case of any trouble. The Japanese periodically beat the men with a heavy board. Any Filipino unlucky enough to pass along the road was forced to strike the men in the face with this club. If the Japanese did not think the Filipinos put enough force into their blows, the Filipinos themselves were beaten.

The amazing thing was the ability of the three men to stay alive, if indeed they were still alive at the end of the second day of this treatment -- they were battered beyond recognition, with the ear of one prisoner hanging down to his shoulder.

I think we all prayed for the men during this ordeal. I know I did. And I am sure all of us said a prayer of relief when the Japanese finally cut the men down and took them away for execution. Two of the men were shot. The third was beheaded. There had at no time been a semblance of a trial.1

Despite knowing of these terrible risks McCoy led nine other men in a successful escape in the spring of 1943. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross after they made a long journey on foot, in the most arduous conditions across enemy held territory, before finally finding a launch and navigating to a Philippine guerrilla outpost at Misamis Occidental.

From Ten Escape from Tojo, available online, one of the first eyewitness accounts of the treatment of US Prisoners of War by the Japanese, first published in 1943.