"ARBEIT MACHT FREI"

10th April 1943: 'Work will make you free' - alongside the mass murder of the Holocaust more than a million Poles died in punitive labour camps

The network of concentration camps built by the Nazis as part of their plan to exterminate the Jews of Europe were also occupied by many non-Jews. Anyone in the occupied territories of Europe might fall victim to them. Mere suspicion of involvement in any form of resistance to the Nazis was grounds for summarily dispatching people to any one of hundreds of labour camps. In these camps, hundreds of thousands of people were worked to death during the course of the war.

Every single nationality that had been subjugated by the Nazis was represented among those imprisoned. People from all corners of Europe were to be found in a grim battle for personal survival - Greeks and Norwegians found themselves alongside French and Russians.

One country was disproportionately represented - Poland. Aside from the 3 million Polish Jews murdered by the Nazis, it is believed that 2.8 million other Poles died during the war - either shot out of hand or worked to death in a labour camp. Stefan Duszka1 was 22 when he was arrested during a round-up in Kozienice in early 1943. He arrived in Gros Rosen in April 1943:

Days later the train came to a halt. As we got off the train, we were ironically greeted by a marching band. We passed through a gate, above which was a large sign which said "ARBEIT MACHT FREI" (Work Will Make You Free). The electrified barbed wire fence with the watchtowers and armed guards did not indicate that there was any way to become free from that place. In my first conversation with the "Veteran" residents I learned that I was now in Gross Rosen Concentration Camp. They assured me that one entered this place through the gate, but that the only way I, or anyone, would leave would be through the crematorium chimney.

The part of my stay at Gross Rosen that will never leave my memory is the camp's bathhouse. Our entire transport, moved along with shouts and beatings, hurried naked into the bathhouse. We were packed into a shower room like sardines.It was unbelievably hot and the air was suffocating. Yet no water came out of the shower heads. A few drops dripped out every few seconds from some of them, and waiting below each were dozens of parched throats. The weaker prisoners would pass out, and then be dragged into the corners where they convulsed and died in agony.

After several hours of this torture, we were let out, a few dozen at a time, and led to a pool filled with ice-cold water. It was the beginning of April and the weather was still winter. In this way more of the weaker prisoners were finished off.

We, the newcomers, were transformed into prisoners in a very abrupt manner. Barbers shaved off our hair and we were issued the infamous striped prison uniforms with berets made of the same striped cloth. Two thugs at each door hurried us along with blows of their clubs on our naked bodies.

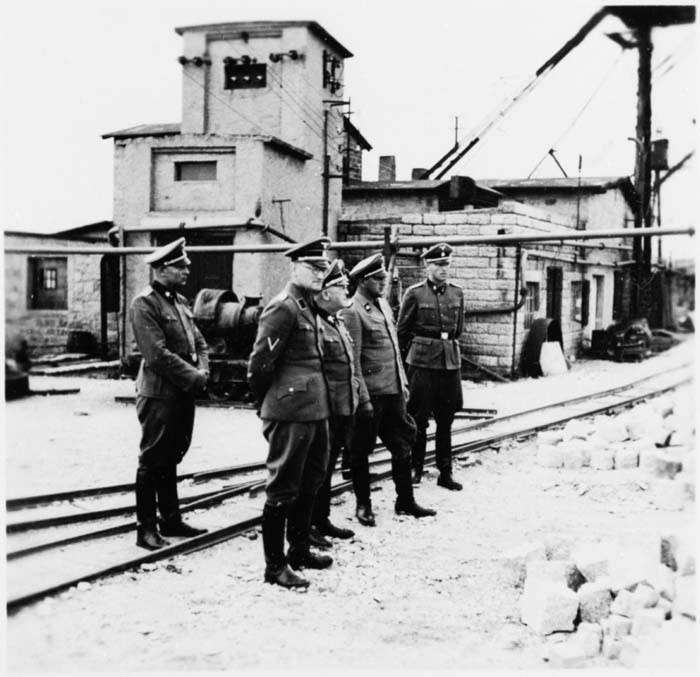

From the very first day we newcomers were introduced to camp discipline. We were mustered into ranks and for hours we were trained on how to correctly "salute" the camp authorities. It seemed that the main purpose of the striped beret was to "greet" passing SS men with it. We were to stand at rigid attention at an appropriate distance from the SS man, and snatch our beret from our heads with lightning speed and slam it in salute against our hip. Anyone who did not salute an SS man in this way was severely beaten, sometimes to death.

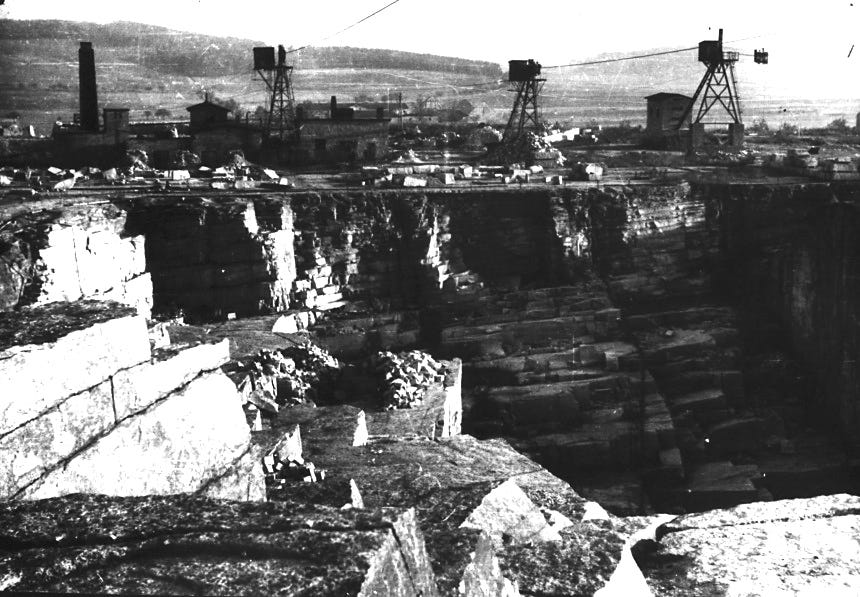

ork assignment was in the stone quarry. My first job was to load stones into carts. We had to work in the open air, whatever the weather, from dawn to dusk. We worked without a break, under the watchful eyes and the brutal clubs of the "Kapos."

The Kapos were the concentration camp's gang foremen. They were usually German, and had criminal records and sadistic inclinations. They held absolute power of life and death over their gangs. It seemed that the more cruelty they exhibited, and the greater the pain they inflicted, the greater they were esteemed by the camp administration.

My gang dug trenches, shoveled sand, broke stones with sledge hammers, and carried away the rock. When we had the sledges in our hands, they had to keep in constant motion, and had to strike hard blows with each and every swing. When working with the shovels, they to had to be in constant motion, and full to the edges with each movement. When we carried rocks, it had to be done at a run, and God help you if the rock was too small. And so it went, hour after hour, day after day, without a break.

The veteran prisoners had already mastered the art of "working with their eyes." This consisted of carefully watching the Kapo. The instant his attention was somewhere other than on you, you could relax for a moment. This called for lightning reflexes, and you had to anticipate the instant when the Kapo would again turn in your direction. If you did not have quick reflexes, you did not attempt to "work with your eyes." The Kapos or the SS would finish you off in an instant.

Our number one enemy was hunger. The normal human organism would survive no longer than three months on the calories we were allotted. These starvation rations were further reduced by the thievery and corruption of the Kapos and the camp administration.

Besides hunger, cold was our greatest enemy, especially during the winter. The cold autumn rains were also devastating. Our soaked uniforms would not dry overnight in the unheated barracks, and we would have to work for days in our wet uniforms. We tried to keep warm any way we could. For example, we would wear old cement sacks under our uniforms. But pity the person who was caught wearing such a "sweater”.

Some of the inmates were at the end of their strength, and lost the will to live. We referred to these listless people in camp jargon as "Muselmann." For a Muselmann the only hope for surviving the winter was to go to the camp hospital, but it was difficult to be admitted. Inmates often injured themselves on purpose in the hope of getting in for a few weeks. It was difficult to call this facility a hospital, but it did keep you out of the cold and away from the murderous labor.

My work in the quarry so exhausted me physically and spiritually that I was close to going to the crematorium. My will had been so weakened that despite the fact that I was ill, I did not even try to get into the hospital. I became a Muselmann.

Stefan Duszka survived only because he had technical skills that saw him transferred to a labour camp building the V1 and V2 rockets - the work was less physically demanding.