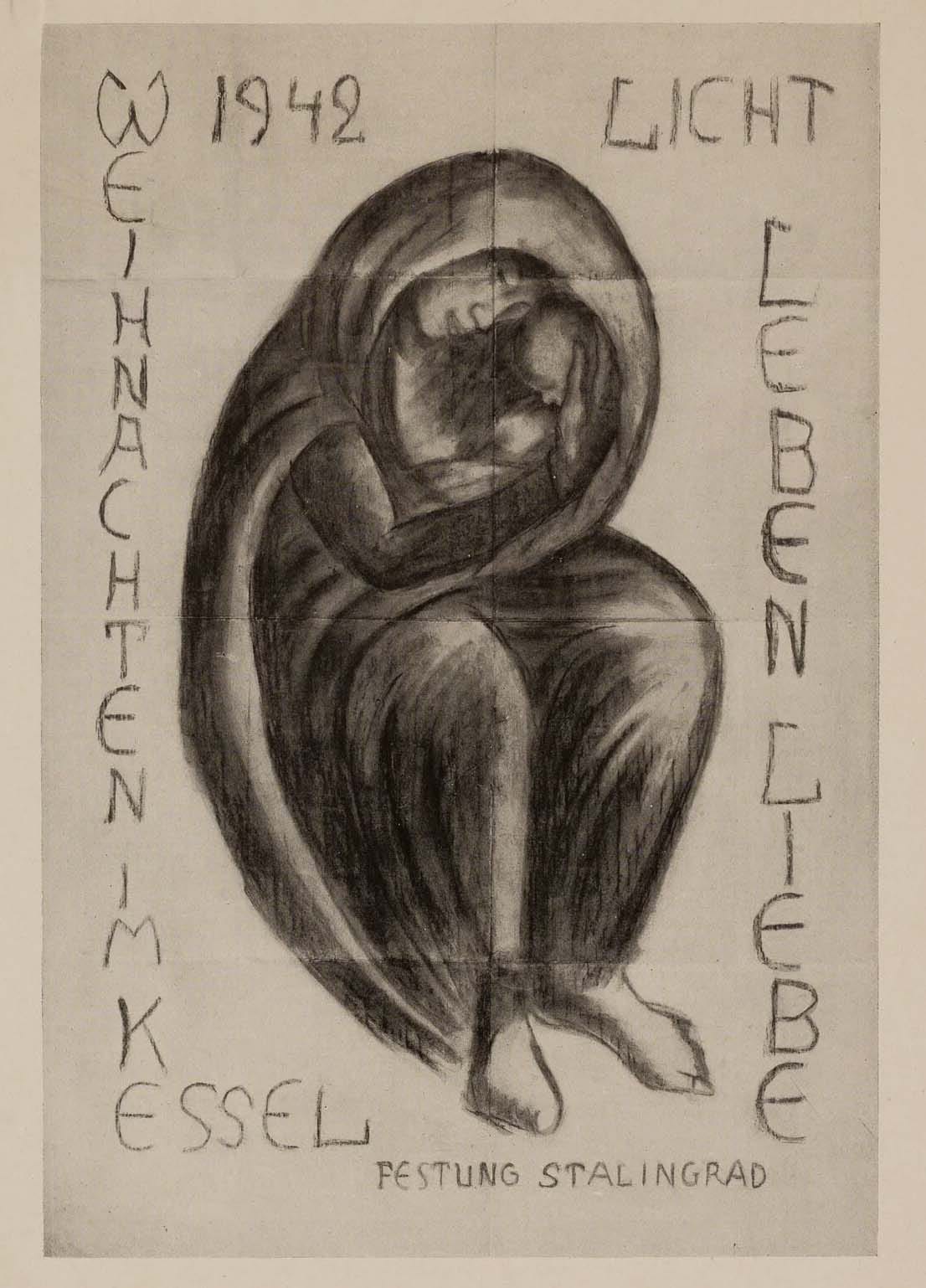

A grim 'Holy Eve' in Stalingrad

24th December 1942: For many German Christians Heilige Abend, or Holy Eve, is the most celebrated part of Christmas - but it is now unbearably poignant

Around a quarter of a million German troops remained in Stalingrad. As they struggled with the deep cold, with little fuel for fires, they huddled in bunkers and endured periodic Russian bombardments. The much-reduced food ration was now a starvation diet and everyone was suffering.

But now the desperate situation got worse. The last hope that they might be rescued faded away as they learnt that ‘Operation Winter Storm’ had failed. The widespread realisation that they were all trapped, with no prospect of relief, came just before Christmas. Only the most seriously wounded had any chance of being flown out.

As Christmas aproached prayers offered some solace. Even in Hitler’s Wehrmacht, there were many Christians. Among them was Lieutenant Kurt Reuber, a staff physician and Protestant pastor:

I have turned my hole in the frozen mud into a studio. The space is too small for me to be able to see the picture properly, so I climb on to a stool and look down at it from above, to get the perspective right. Everything is repeatedly knocked over, and my pencils vanish into the mud.

There is nothing to lean my big picture of the madonna against, except a sloping, home-made table, which I can just manage to squeeze past. There are no proper materials and I have used a Russian map for paper. But I wish I could tell you how absorbed I have been painting my madonna, and how much it means to me.

...

It is intended to symbolize 'security' and 'mother love.' I remembered the words of St. John: light, life, and love. What more can I add? I wanted to suggest these three things in the homely and common vision of a mother with her child and the security that they represent.

...

When according to ancient custom I opened the Christmas door, the slatted door of our bunker, and the comrades went in, they stood as if entranced, devout and too moved to speak in front of the picture on the clay wall...The entire celebration took place under the influence of the picture, and they thoughtfully read the words: light, life, love...Whether commander or simple soldier, the Madonna was always an object of outward and inward contemplation.

The Madonna was flown out of Stalingrad by a battalion commander of the 16th Panzer division on the last transport plane to leave the encircled German 6th Army.

Reuber was taken captive after the surrender of the 6th Army and died in a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp in 1944.

The original is displayed in the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Berlin, and copies now hang in the cathedrals of Berlin, Coventry and Volgograd (the former Stalingrad) as a sign of the reconciliation between Germany and her former enemies, the United Kingdom and Russia.

The Soviet Army was slow to realise the significance of Christmas to the Germans trapped at Stalingrad. If they had appreciated the special place of Heilige Abend, or Holy Eve, in the German calendar the bombardment might well have been greater that day.

As the news gradually sunk in that they were not going to break out, and the relieving forces were not going to be able to reach them, it would have been a hard day anyway.

But for this to happen at such a time was very hard to bear. Hans-Erdmann Schonbeck1 was a 20-year-old officer with the 24th Panzer Division:

The noise of battle from the relief army had been getting closer day by day. We were geared up for the last leap westwards, to meet our liberators. But only in our minds, for we knew that we were almost out of fuel and ammo.

With the first day of Christmas came the full, awful certainty. The relief troops were unable to make it, the battle sounds were getting fainter and moving to the west. Our thoughts of escape had been in vain.

...

On December 24th there were about fifteen men in my bunker. That morning, under fairly heavy fire, I had managed to dig up a little pine tree buried in the snow of the steppe - probably one of the very few Christmas trees in the entire Kessel.

That spring, when I’d been billeted with a priest in Brittany I’d scrounged three church candles that were just the right size to fit into my backpack. I had no idea why at the time, I just liked the look of them.

It got dark very early. The candles were burning as I told the Christmas story and spoke the Lord’s Prayer.

A little later, the crackly loudspeaker transmitted a Christmas message from the Forces’ radio station in Germany. It was being broadcast everywhere from the North Pole to Africa. At that time an enormous part of the world belonged to us.

When Stalingrad was called we began to tremble though we were indoors in the warm that evening. Then when the words ‘Stille Nacht; heilige Nacht ...’ were sung, our tears started to flow. We cried for a long time. From that moment, no one said so much as a word - maybe for a whole hour.

The German Army choir that supposedly sang 'Silent Night, Holy Night' from their positions in 'Fortress Stalingrad' was a total invention by the Nazi propaganda machine - the choir was actually broadcasting from Berlin. Many of the men inside the besieged pocket were upset by this false presentation of their plight.

This account is one of many that appears in Voices from Stalingrad.