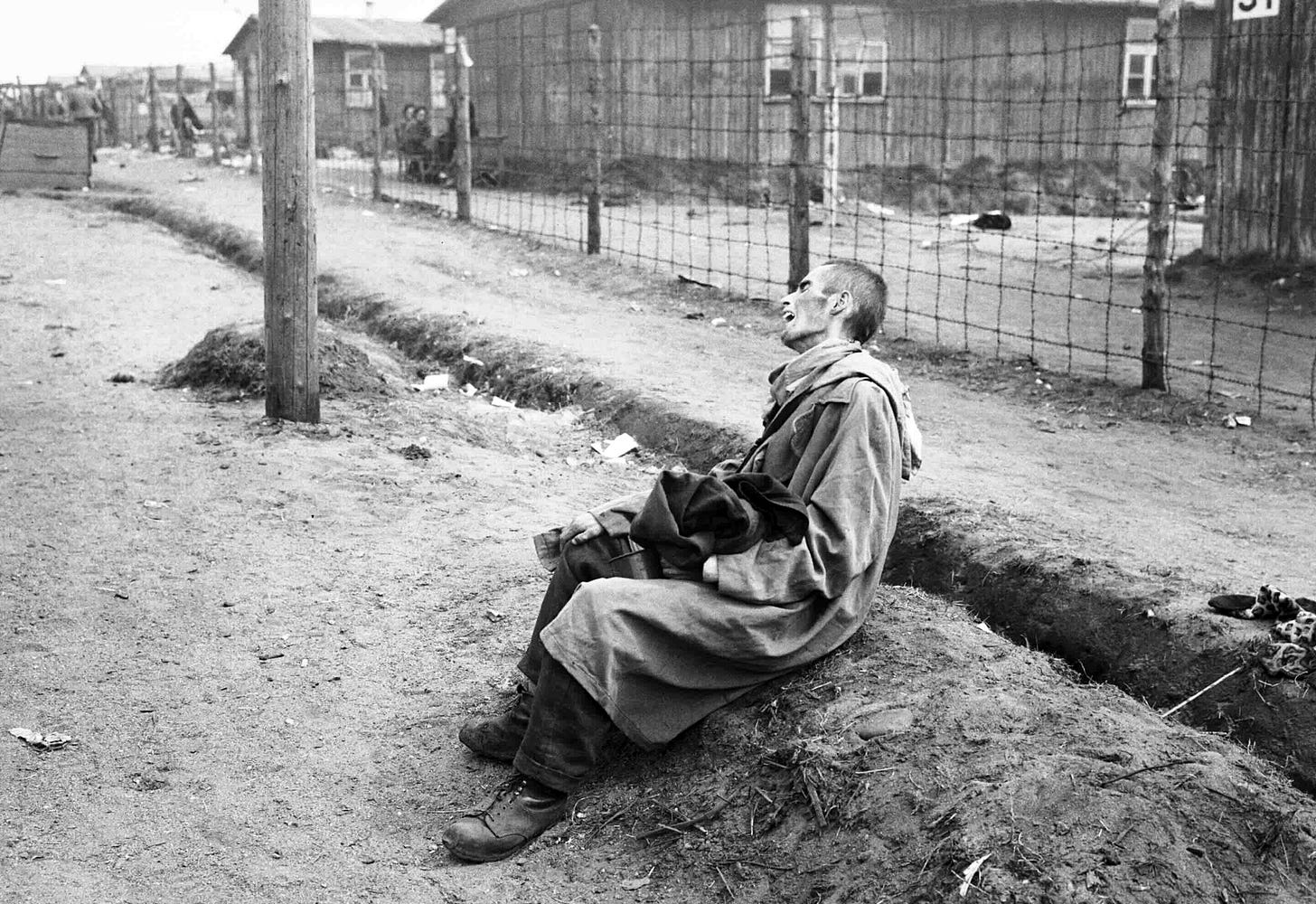

Bergen-Belsen liberated

15th April 1945: The reality of the Holocaust shocks British soldiers as yet another grim discovery is made by the Allies pushing into Germany

In the past few days, the US Army had uncovered terrible examples of the horrors of the Nazi regime - systematic at Buchenwald, and unplanned and haphazard on the outskirts of Gardelegen. But these were just part of a murderous totalitarian state. They were a means of controlling ‘undesirable’ groups, including German citizens.

An even more terrible aspect now emerged. Hitler had been engaged in an unprecedented attempt to exterminate an entire ‘racial group’ across Europe - the Jews. The word genocide had not yet been invented. But the evidence of industrial-scale mass murder suddenly thrust itself into the public consciousness.

It1 was about 5pm on 15 April when the miracle actually happened: the first British tank rolled into the camp. We were liberated! No one who was in Belsen will ever forget that day. We did not greet our liberators with shouts of joy. We were silent. Silent with incredulity and maybe just a little suspicion that we might be dreaming.

This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.

It was the pictures and stories from the first concentration camps liberated, Buchenwald and Bergen Belsen, that first made a real impact on public consciousness of the Holocaust. It was these names that became closely associated with the worst horrors of the Nazi system of brutality, even though they were, in some senses, not the ‘worst’ camps.

These were not extermination camps like Auschwitz, where people were sent to be killed immediately if they did not survive 'the selection'. They were nevertheless lethal systems of incarceration and no less murderous over time.

Here2 over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which... The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them ... Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live ... A mother, driven mad, screamed at a British sentry to give her milk for her child, and thrust the tiny mite into his arms, then ran off, crying terribly. He opened the bundle and found the baby had been dead for days.

This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.

Bergen-Belsen had gone through a number of incarnations, starting out as a Prisoner of War camp for Soviet prisoners at a time when the Nazis seemed intent on letting them all starve to death. Some 20,000 died here. Then, as an SS concentration camp for Jews who might be used as hostages, the conditions here were probably somewhat better than at many other work camps. Then, a variety of different groups were sent or passed through, including many women and girls - Ann Frank died here.

Inside the camp itself, it was just unbelievable. You just couldn’t believe the numbers involved...

Then, at the end of 1944, Bergen Belsen started receiving prisoners who had survived the forced marches from the camps in the East. Soon, its primitive facilities were overwhelmed by over 60,000 sick and malnourished people. They had been dying in their hundreds every day for months. They would continue dying in their hundreds every day for the next two months, despite the best efforts of the Allied medical teams.

But we3 went further on into the camp, and seen these corpses lying everywhere. You didn’t know whether they were living or dead. Most of them were dead. Some were trying to walk, some were stumbling, some on hands and knees, but in the lagers, the barbed wire around the huts, you could see that the doors were open. The stench coming out of them was fearsome.

They were lying in the doorways – tried to get down the stairs and fallen and just died on the spot. And it was just everywhere. Going into, more deeper, into the camp the stench got worse and the numbers of dead – they were just impossible to know how many there were...Inside the camp itself, it was just unbelievable. You just couldn’t believe the numbers involved...

this oppressive haze over the camp, the smell, the starkness of the barbed wire fences, the dullness of the bare earth, the scattered bodies …

This was one of the things which struck me when I first went in, that the whole camp was so quiet and yet there were so many people there. You couldn’t hear anything, there was just no sound at all and yet there was some movement – those people who could walk or move – but just so quiet. You just couldn’t understand that all those people could be there and yet everything was so quiet...

It was just this oppressive haze over the camp, the smell, the starkness of the barbed wire fences, the dullness of the bare earth, the scattered bodies and these very dull, too, striped grey uniforms – those who had it – it was just so dull. The sun, yes the sun was shining, but they were just didn’t seem to make any life at all in that camp.

Everything seemed to be dead. The slowness of the movement of the people who could walk. Everything was just ghost-like and it was just unbelievable that there were literally people living still there. There’s so much death apparent that the living, certainly, were in the minority.

What happened was we4 were all allocated to a hut. We divided into pairs, as I said, and each pair was given a hut to cope with. And into the hut you went and it was designed, I think, to take about 60 soldiers. It was a typical army Nissen hut-type – only it wasn’t a Nissen hut because it wasn’t the same shape – and inside it were upwards of six or seven hundred people lying on the ground.

They were all totally emaciated. They were all in filthy rags – rags is literally what I mean, rags. They were all, or most of them, lying in pools of vomit and faeces and urine. A considerable number of the ones in the hut were dead and the first job to do each day was to go in, and with the help of two Hungarian soldiers – strangely enough we had a company of Hungarian soldiers to help as labourers – you’d go into the hut and pick out the dead bodies. You’d just go around and see who’s dead and who wasn’t.

They all had the most appalling coughs, they all had the most dreadful skin diseases, they were all filthy dirty and they were all absolutely skeletally thin..

It was sometimes very difficult to be certain who was dead and who wasn’t.

Remove the dead, take them outside, leave them in a heap and the Hungarians then moved them by truck to the mass graves where they were put in the mass graves. And having got rid of the dead you then made a sort of so say ward round to try and do what you could for the remainder, all of whom had diarrhoea, or the vast majority had diarrhoea.

They all had the most appalling coughs, they all had the most dreadful skin diseases, they were all filthy dirty and they were all absolutely skeletally thin... And we were dealing with the killer, the main killer, which was typhus. And typhus was killing a very large number of people every day.

These people had been degraded by the Germans. It was a systematic depersonalisation …

These people had been degraded by the Germans5. It was a systematic depersonalisation, degradingness. They’d been for as long as they’d – the Germans had degraded these people from the time they’d occupied their countries. They degraded them by putting them into ghettos, they degraded them by making them into second and third class citizens, they degraded them by herding them like cattle, by transporting them in conditions which were worse than animals would be transported, by totally dehumanising them.

It could only be done by moving masses of people by rail. It had to be planned and worked for. It was a sort of death by administration.

Something had changed for me6 after I’d seen that camp. Although I’d seen the terrible things in war, to have treated ordinary people like this. And there were so many theories and reasons as to who was responsible and everybody seemed to point a finger around until the finger came round in a circle and I had to think hard about it.

Why the Germans? They had their own culture, their own civilisation of a kind. They produced Beethoven, great scientists, how could it be?

The terrible discovery came to me, this sort of revelation like a flash of lightning, because it penetrated these terrible scenes to make me think – all the stories I’d heard about the persecution of people from my mother and father, here they were true.

But this was on a scale of – it had to be organised, it had to be done it could only be done with modern administrative service. It could only be done by moving masses of people by rail. It had to be planned and worked for. It was a sort of death by administration.

Two days after I regained consciousness, on 27 April, my mother died aged 42 and was buried in a mass grave

As soon as possible, we7 were transferred to the tank training school six kilometres away for delousing and then to makeshift hospitals, where German doctors and nurses were made to look after us. I was unconscious for 10 days after we were liberated. Two days after I regained consciousness, on 27 April, my mother died aged 42 and was buried in a mass grave, together with the thousands of others who died from starvation and disease after the liberation.

Survivor Anita Lasker-Wallfisch

BBC radio broadcaster Richard Dimbleby in a historic broadcast made just days after the liberation, that alerted the British and the world to the worst horrors of Nazism.

British soldier Dick Williams

Medical student Roger Dixey

Dr Laurence Wand

British soldier Mike Lewis

Survivor Renée Salt

For more on the liberation of Belsen and its context in the concentration camp system, see the 60th Anniversary Guide by the British Government. Quotes from British soldiers are transcripts of some of the audio recordings made by the Imperial War Museum.