'Unbelievable' horror of Majanek

11th August 1944: The BBC refuse to carry a report from their correspondent because the scale of the crimes committed by the Nazis is beyond belief

By August 1944, the Allies had mounting evidence of the Nazi mass murder of Jews - and their plans to murder all the Jews in Europe. They had detailed accounts that the Polish Resistance had smuggled out to Switzerland and the world. The most recent reports from escapees from Auschwitz had arrived only recently. The Nazi treatment of Jews had been condemned at the highest levels. Yet the enormity of Nazi crimes made these reports "incredible" - people just could not really believe them.

Nearly two thousand people could be disposed of here simultaneously.

Now the advancing Red Army uncovered the physical evidence of the extermination camps. The camp at Majdanek, [also spelled Maidanek] in eastern Poland had been overrun on 23 July. Soviet reports on the scale of the killing there, and at nearby Treblinka, were already being published when respected British journalist Alexander Werth1 arrived at the camp in August.

The evidence was widespread, from the piles of human ashes the SS had used to fertilise their cabbages, from the mountains of shoes left behind by tens of thousands of men, women and children, and from the eyewitness accounts of the citizens of Lublin. But the enormity of the crime made it impossible to comprehend that industrial-scale killing had actually taken place here.

“Unbelievable” it was: when I sent the BBC a detailed report on Maidanek in August 1944, they refused to use it; they thought it was a Russian propaganda stunt, and it was not till the discovery in the west of Buchenwald, Dachau and Belsen that they were convinced that Maidanek and Auschwitz were also genuine...

As a consequence, Werth's report on his visit to Maidanek was not published at the time and did not appear until after the war:

My first reaction to Maidanek was a feeling of surprise. I had imagined something horrible and sinister beyond words. It was nothing like that. It looked singularly harmless from outside. “Is that it? ” was my first reaction when we stopped at what looked like a large workers’ settlement. Behind us was the many towered skyline of Lublin.

There was much dust on the road, and the grass was a dull, greenish-grey colour. The camp was separated from the road by a couple of barbed-wire fences, but these did not look particularly sinister, and might have been put up outside any military or semi-military establishment. The place was large; like a whole town of barracks painted a pleasant soft green.

There were many people around - soldiers and civilians. A Polish sentry opened the barbed-wire gate to let our cars enter the central avenue, with large green barracks on either side. And then we stopped outside a large barrack marked Bad und Desinfektion II. “This,” somebody said, “is where large numbers of those arriving at the camp were brought in.”

The inside of this barrack was made of concrete, and water taps came out of the wall, and around the room there were benches where the clothes were put down and afterwards collected. So this was the place into which they were driven. Or perhaps they were politely invited to “Step this way, please?” Did any of them suspect, while washing themselves after a long journey, what would happen a few minutes later? Anyway, after the washing was over, they were asked to go into the next room; at this point even the most unsuspecting must have begun to wonder.

For the “next room” was a series of large square concrete structures, each about one-quarter of the size of the bath-house, and, unlike it, had no windows. The naked people (men one time, women another time, children the next) were driven or forced from the bath-house into these dark concrete boxes - about five yards square - and then, with 200 or 250 people packed into each box - and it was completely dark there, except for a small skylight in the ceiling and the spyhole in the door - the process of gassing began.

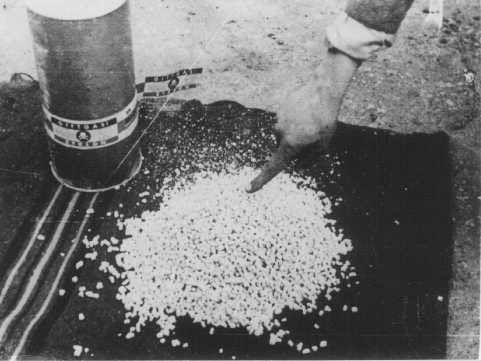

First some hot air was pumped in from the ceiling and then the pretty pale-blue crystals of Cyclon were showered down on the people, and in the hot wet air they rapidly evaporated. In anything from two to ten minutes everybody was dead... There were six concrete boxes - gas-chambers - side by side. “Nearly two thousand people could be disposed of here simultaneously,” one of the guides said.

But what thoughts passed through these people’s minds during those first few minutes while the crystals were falling; could anyone still believe that this humiliating process of being packed into a box and standing there naked, rubbing backs with other naked people, had anything to do with disinfection?

At first it was all very hard to take in, without an efiort of the imagination. There were a number of very dull-looking concrete structures which, if their doors had been wider, might anywhere else have been mistaken for a row of nice little garages. But the doors- the doors! They were heavy steel doors, and each had a heavy steel bolt.

And in the middle of the door was a spyhole, a circle, three inches in diameter composed of about a hundred small holes. Could the people in their death agony see the SS-man’s eye as he watched them? Anyway, the SS-man had nothing to fear: his eye was well-protected by the steel netting over the spyhole. And, like the proud maker of reliable safes, the maker of the door had put his name round the spyhole: “Auert, Berlin”.

Then a touch of blue on the floor caught my eye. It was very faint, but still legible. In blue chalk someone had scribbled the word “vergast” and had drawn crudely above it a skull and crossbones. I had never seen this word before, but it obviously meant “gassed” - and not merely “gassed” but, with that eloquent little prefix ver, “gassed out”. That’s this job finished, and now for the next lot. The blue chalk came into motion when there was nothing but a heap of naked corpses inside. But what cries, what curses, what prayers perhaps, had been uttered inside that gas chamber only a few minutes before?

Yet the concrete walls were thick, and Herr Auert had done a wonderful job, so probably no one could hear anything from outside. And even if they did, the people in the camp knew what it was all about.

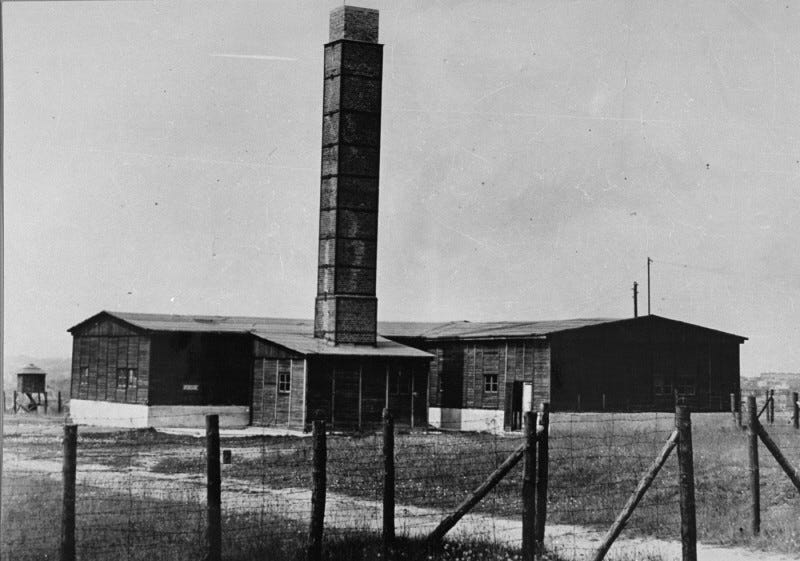

It was here, outside Bad und Desinfektion II, in the side-lane leading into the central avenue, that the corpses were loaded into lorries, covered with tarpaulins, and carted to the crematorium at the other end of the camp, about half-a-mile away.

Between the two there were dozens of barracks, painted the same soft green. Some had notice-boards outside, others had not.

Thus, there was an Effekten Kammer and a Frauen-Bekleidungskammer; here the victims’ luggage and the women’s clothes were sorted out, before they were sent to the central Lublin warehouse, and then on to Germany.

None of the SS should have ever survived capture. Particularly the Waffen SS scum.