Escape from Auschwitz

7th April 1944: Two prisoners outwit the SS in a daring escape so that they can tell the world of the enormity of the crimes being committed

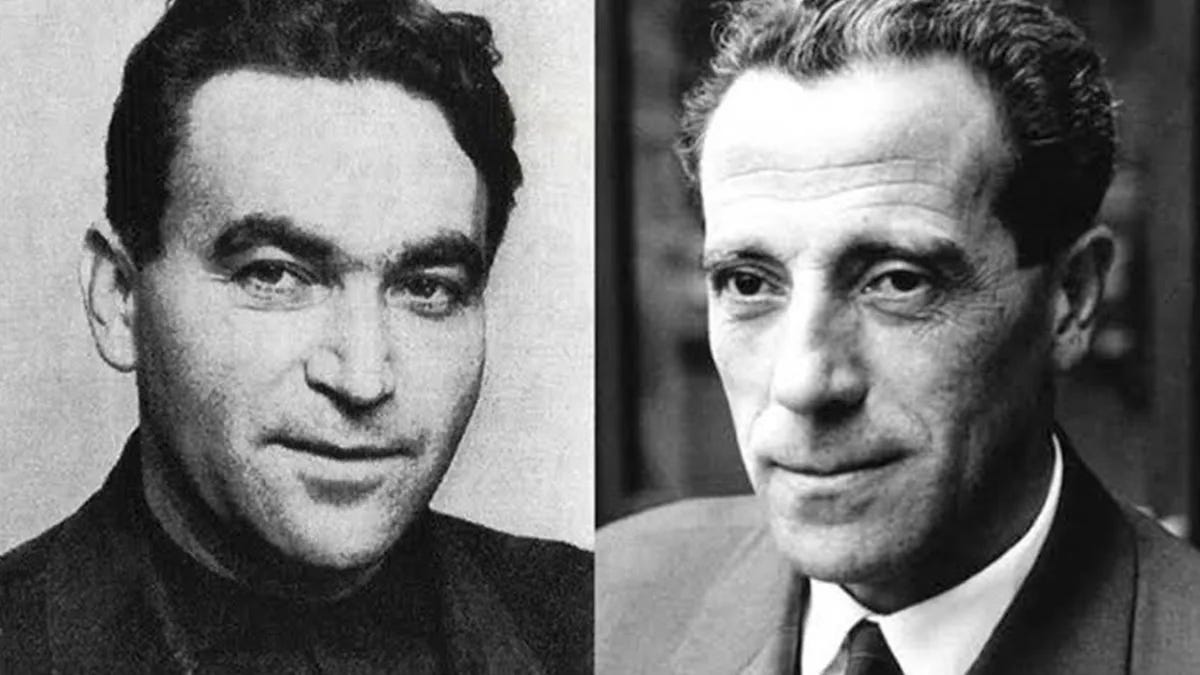

Nazi Germany had occupied its ally Hungary in March. Learning of the imminent arrival of Hungarian Jews for the gas chambers of Auschwitz, two of the more experienced prisoners now made a desperate attempt to warn the outside world. Rudolf "Rudi" Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg, Vrba was the name given to him by the Slovak resistance) and Alfred Wetzler (Fred in Vrba's account) had planned their attempt for some time. They were to take with them evidence of the extermination facilities.

They knew they could not get completely away from the camp in one move. They, therefore, chose to hide in a cavity within a pile of planks that lay in the work area of the camp. For this they needed the assistance of a few other prisoners. After a last-minute encounter with an SS guard, who nearly searched him, Rudolf Vrba1 found the hiding place:

I could see the wood now and the Poles on top of it, apparently working. Fred was there, too, and the three of them gaped a little when they saw me, for they felt sure I was already in the punishment block. Nobody spoke, however. The Poles moved the planks and gave us an almost imperceptible nod.

This was it. For a moment we both hesitated, for we knew that, once we were covered up, there was no going back. Then together we skipped quickly up on top of the wood and slid into the hole. The planks moved into place over our heads, blotting out the light; and there was silence. Our eyes soon got used to the gloom and we could see each other in the light that filtered through the cracks. We hardly dare to breath, let alone to talk.

...

I took out my powdery Russian tobacco and began pulling it into the narrow spaces which separated some of the planks, while Fred sat, watching me in the gloom.

It took me at least an hour to impregnate our temporary prison thoroughly with dog repellant. Then I sat down, leaned against the rough, wooden wall and concentrated on some positive thinking. I forced my mind away from all thoughts of discovery and told myself over and over again: “There’ll be no more rolls calls. No more work. No more kow-towing to S.S. men. Soon you'll be free !”

Free - or dead. I felt the keen blade of my knife and swore to myself that, if they found me, they would never get me out of the cavity alive. Time stood still. I glanced at the watch which had nearly cost me my life and saw that it was only half past three. The alarm would not be raised until five thirty and suddenly I realised I was longing to hear it. I felt like a boxer, sitting in his corner, waiting for the bell, or like a soldier in the trenches, waiting to go over the top. I feared the wail of that siren. Yet I could not bear the waiting. I wanted the battle to begin.

We could not stand up and became cramped sitting. We did not dare to talk and that made time hang even more heavily. The movements of the camp, movements we both knew by heart, drifted faintly into our hole in the wood, but somehow it all seemed far away in time, as well as in distance, for already my mind was free in advance of my body.

For the next hour I kept glancing at my watch, holding it to my ear occasionally to see whether it had stopped. Then I disciplined myself to ignore it, grinning in the dark as I thought fatuously of my mother in her kitchen back home, shaking her finger at me and saying solemnly: “A watched pot never boils!"

In fact it was never necessary for me to look at my watch, for the noises in the camp outside told me roughly what time it was. At last, after what seemed a week, I heard the tramp of marching feet and at once every fibre was alert. The prisoners were coming back from work. Soon they would be lining up in their neat rows of ten for roll call. Soon we would be missed; and then there would be the siren, the baying of the dogs, the clatter of S.S. jack boots.

We heard the distant orders, faint, disembodied, like lonely barking at night. We saw in our minds the entire scene which would never be part of our lives again. The rigid rows of the living. The silent piles of the dead. The kapos and block leaders, snapping at their charges, fussing, panicking. The S.S., aloof, superior, totting up their units.

Vrba and Wetzler were to lie in their hideout, concealed within the woodpile for three days. They knew from previous escape attempts that the SS would maintain their guards around the outer perimeter for this period, whilst repeated searches were made of the area inside and outside the perimeter.

Their defences against dogs sniffing them out were put to the test on several occasions during the next there days.

Finally, on the 10th they emerged and managed to make their way across country back to their home in Slovakia. They arrived on the 25th April and had written their report by the 27th. Having passed on the report to the underground Slovak Jewish Council, further action was out of their hands.

The report did not arrive in time to prevent the first transports of Jews from Hungary, which began in mid-May 1944. Nevertheless, it was instrumental in the deportations later being halted by the Hungarian government on 7th July, saving the lives of over 120,000 - 200,000 Jews. The report was first published in the USA in November 1944.

Rudolf Vrba: I Escaped from Auschwitz. First published as ‘I Cannot Forgive’.