Survival in Auschwitz - understand the system

28th February 1944: One of the great chroniclers of the Holocaust describes the arcane rules that must be followed to have a chance of survival

With the German takeover of Italy in September of 1943 conditions rapidly worsened for the Jewish population. Although Mussolini had run anti-semitic policies which made life very difficult for Jews, the Italian state had not pursued and persecuted them with the same zeal as the Nazis. Now, Jews were being deported to Germany and to the death camps in Poland.

Primo Levi managed to avoid detention for a few months but was caught by the Italian militia after a short spell with the Partisans in the hills. Conditions in his Italian run detention camp were basic but the rations were adequate and the regime was not lethal by design, as in the German camps. All that changed on the 21st February when the Germans took over and deported the Jewish inmates by rail car to Auschwitz.

Levi was sent to Monowitz, one of the Auschwitz sub camps. The average survival time for a Jewish inmate was about three months. To survive meant learning fast about the rules of life and death in this inhuman hell.

Levi was to be an exception because he had the inner strength, and the luck, not only to survive but to live to tell the tale afterwards. His capacity to tell that tale1 established him as one of the great individual chroniclers of Holocaust:

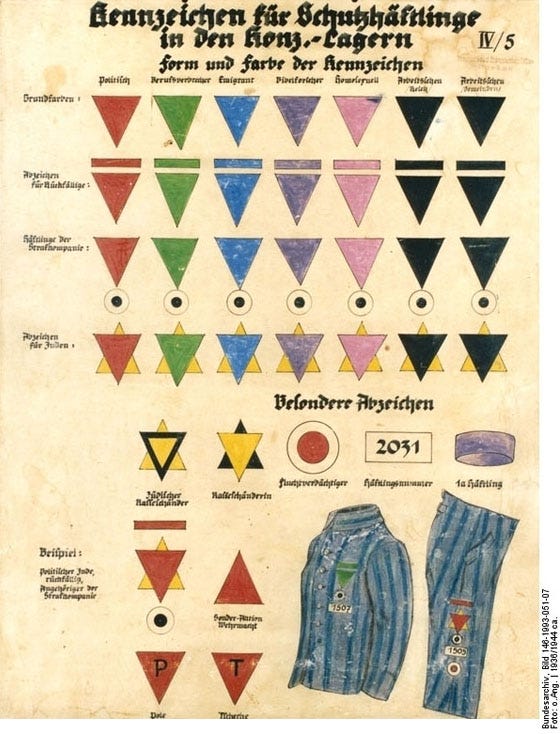

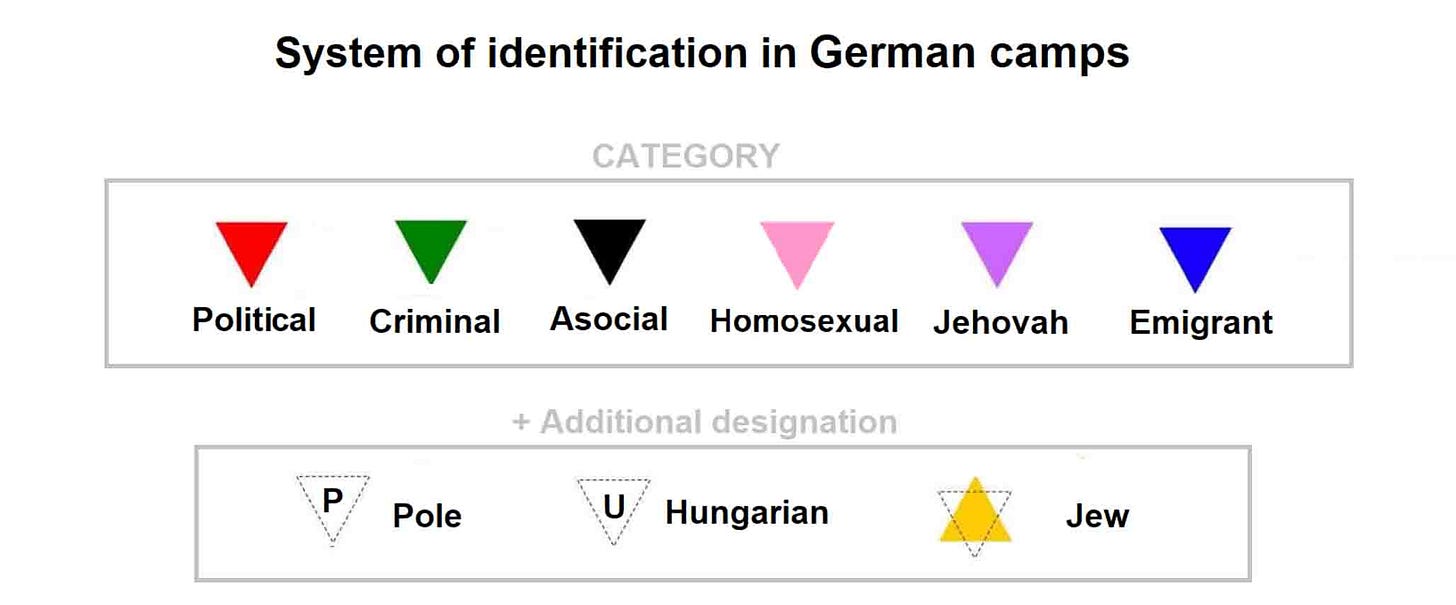

We had soon learned that the guests of the Lager are divided into three categories: the criminals, the politicals and the Jews. All are clothed in stripes, all are Haftlinge [detainees], but the criminals wear a green triangle next to the number sewn on the jacket; the politicals wear a red triangle; and the Jews, who form the large majority, wear the Jewish star, red and yellow.

SS men exist but are few and outside the camp, and are seen relatively infrequently. Our effective masters in practice are the green triangles, who have a free hand over us, as well as those of the other two categories who are ready to help them - and they are not few.

And we have learnt other things, more or less quickly, according to our intelligence: to reply “Jawohl,” never to ask questions, always to pretend to understand.

We have learnt the value of food; now we also diligently scrape the bottom of the bowl after the ration and we hold it under our chins when we eat bread so as not to lose the crumbs. We, too, know that it is not the same thing to be given a ladleful of soup from the top or from the bottom of the vat, and we are already able to judge, according to the capacity of the various vats, what is the most suitable place to try and reach in the queue when we line up.

We have learnt that everything is useful: the wire to tie up our shoes, the rags to wrap around our feet, waste paper to (illegally) pad out our jacket against the cold. We have learnt, on the other hand, that everything can be stolen, in fact is automatically stolen as soon as attention is relaxed; and to avoid this, we had to learn the art of sleeping with our head on a bundle made up of our jacket and containing all our belongings, from the bowl to the shoes.

We already know in good part the rules of the camp, which are incredibly complicated. The prohibitions are innumerable: to approach nearer to the barbed wire than two yards; to sleep with one's jacket, or without one's pants, or with one's cap on one's head; to use certain washrooms or latrines which are “nur fir Kapos” or “nur fir Reichsdeutsche”; not to go for the shower on the prescribed day, or to go there on a day not prescribed; to leave the hut with one's jacket unbuttoned, or with the collar raised; to carry paper or straw under one's clothes against the cold; to wash except stripped to the waist.

The rites to be carried out were infinite and senseless: every morning one had to make the “bed” perfectly flat and smooth; smear one's muddy and repellent wooden shoes with the appropriate machine grease; scrape the mudstains off one's clothes (paint, grease and rust-stains were, however, permitted); in the evening one had to undergo the control for lice and the control of washing one's feet; on Saturday, have one's beard and hair shaved, mend or have mended one's rags; on Sunday, undergo the general control for skin diseases and the control of buttons on one’s jacket, which had to be five.