Mass execution of Hong Kong civilians

29th October 1943: Prisoners defiant to the end as they face execution by the Japanese - but the beheadings are botched

The notorious execution by beheading of Leonard Sifflett is relatively well known - because of the survival of a few photographs of the event. Yet in the same week the Japanese committed a similar but larger atrocity in Hong Kong. Thirty-three civilian detainees and POWS, including one woman, were beheaded for breaching the draconian rules of their detention.

In the summer of 1943, the Japanese uncovered evidence of a 'resistance group' amongst the interned civilians - they set about trying to discover the membership of the group using the most brutal torture. In fact, there was little to discover, the group was trying to smuggle in food from the outside and maintained a radio to listen to world news. However, to be associated with the group would have been fatal. The refusal of those who were arrested to betray others saved many lives. Those arrested included British soldiers, civilians who had served in the Hong Kong administration and some of the Chinese residents they had been in contact with.

Eventually, after a brief trial, they were all condemned to die.

On this occasion the executions were botched. The Japanese had a taste for executions by beheading - despite knowing how easily the process could go wrong. For some of those condemned to die on the 29th October things went horribly wrong, compounding their suffering.

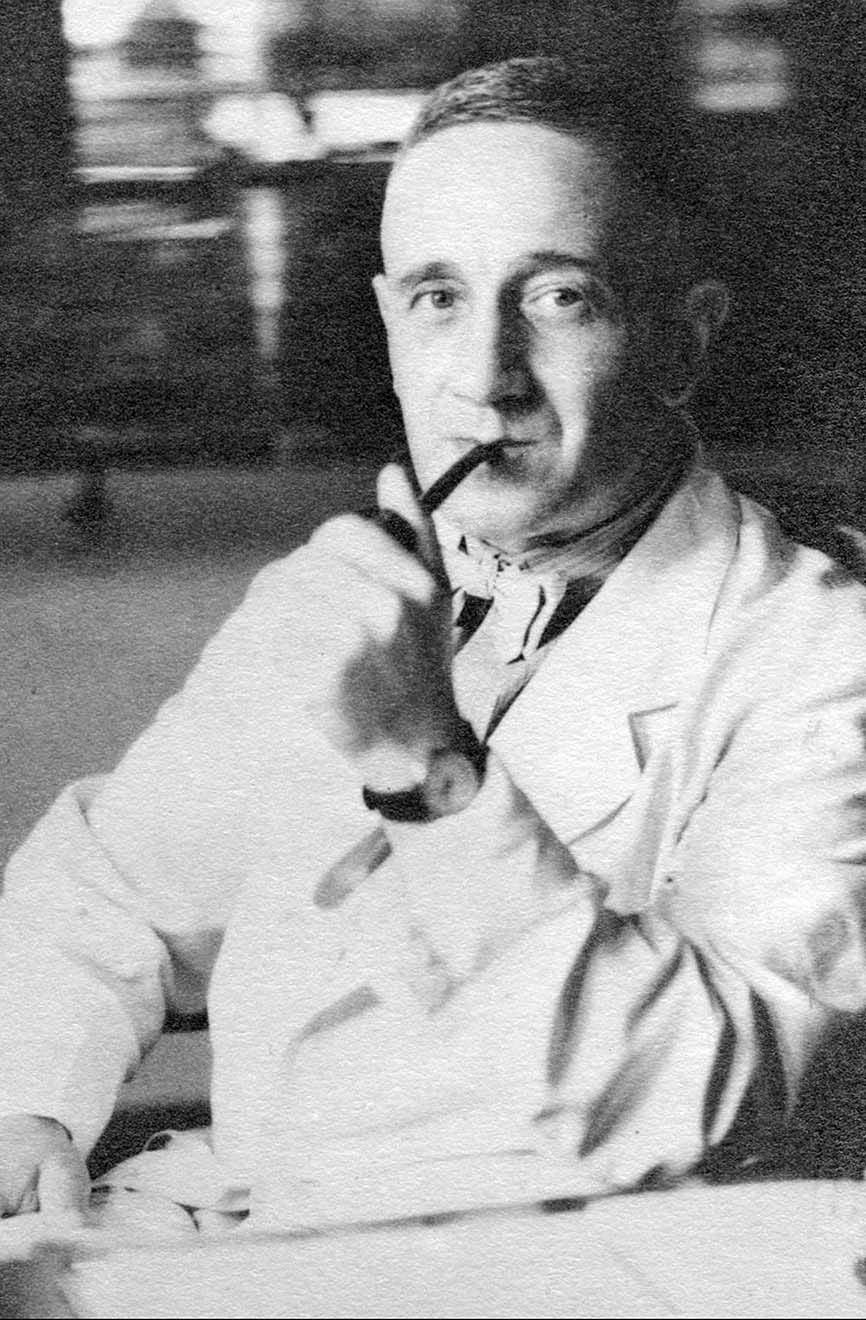

A fellow internee was a senior officer in the Royal Hong Kong Police - George Wright-Nooth was able to piece together the events of that dreadful day:

Hirano was up early on 29 October. He had slept well and, as he buckled on his sword belt over his freshly laundered uniform, he was delighted that his day had come. He was in charge of the actual beheadings, he would strike the first blows, and only when he considered his sword was losing its keenness or his arms their strength would he delegate his duty to others.

He had briefed and practised his assistants the day before and inspected their swords. They were Itano, Kawada, Nishida and Sahara from his staff, plus his rival Takiyawa from the Supreme Court who was certain to be there, itching to exercise his sword arm.

Thirty-two men and one woman - it was a lot. From his previous experience he knew things could go badly wrong. It could be a messy business with blood everywhere, prisoners fainting, or not being killed cleanly. If revolvers had to be resorted to to finish off victims it would be a sign of failure. Hirano hoped that he would be able to send these miserable Chinese and Europeans to a speedy, and what he believed to be, an honourable death.

From the verbal evidence of actual witnesses, mostly Indian warders, it is possible to reconstruct the events of that grim Friday of fifty years ago.

Duggie Waterton had been able to keep a tiny Bible with him in his cell. Shortly before the end he had carefully written a farewell message to his wife and children inside the Bible telling them to be brave, and that he loved them deeply. It is, I believe, virtually impossible to imagine, far less convey, the emotion, the sadness and perhaps the bitterness that goes through a man’s mind when he writes to his loved ones in those circumstances. Waterton passed his Bible to a sympathetic Indian guard asking him to get it to his family somehow.

The warder, weeks later, thrust the Bible into the cell of Lieutenant H.C. Dixon, RNZNVR, an officer serving a sentence in Stanley. Incredibly, Dixon was able to keep it and ensure that Mrs Waterton received it after the war.

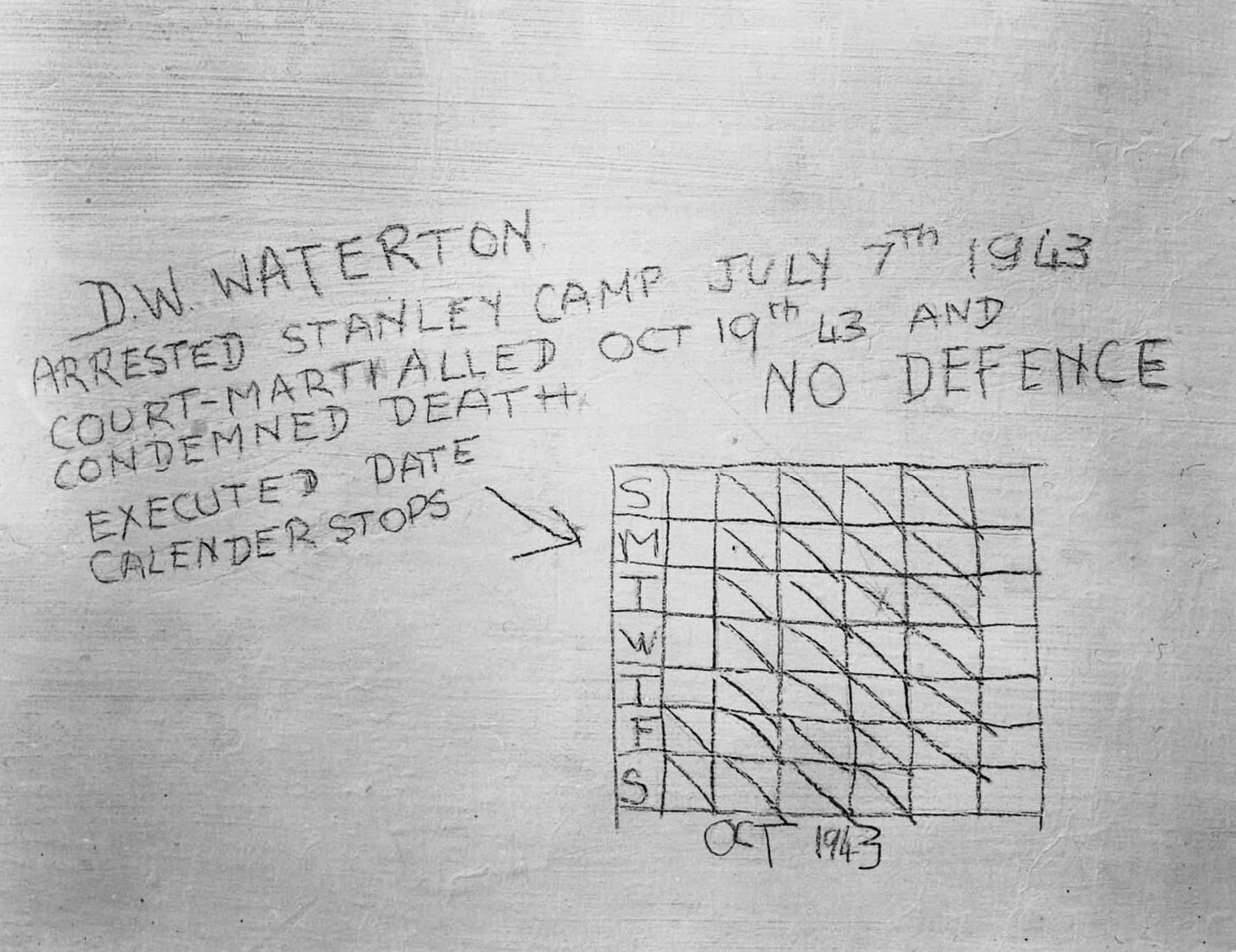

Like numerous other prisoners Waterton had also been able to scratch a last message on the wall of his cell. It read:

D. W. Waterton. Arrested Stanley camp July 17th 1943. Court martialled October 19th 1943 and condemned to death. NO DEFENCE. Executed date calendar stops.

Underneath was a column of squares representing October, 1943. Each square up to the 29th had been crossed through.

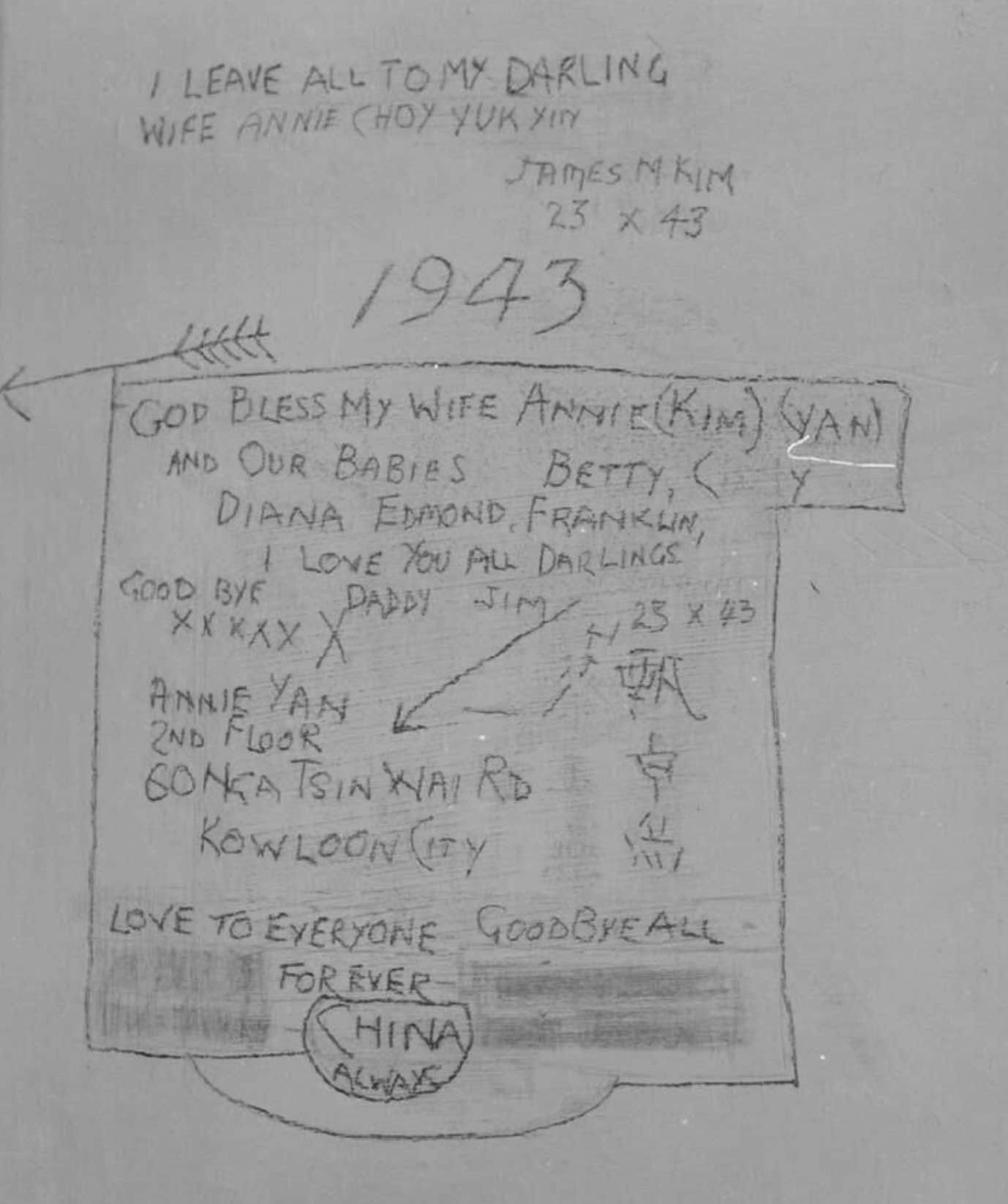

Another condemned man, White, had scratched a full list of the 21 Europeans executed, also with a calendar. Many of these messages, which were noted by Anderson, were later removed on the orders of Redbeard, but at least one survived. It is both a will and a final touching message of love from James Kim to his family.

On the previous day a working party of prisoners from “D” Block had spent an exhausting afternoon digging two long, deep trenches in the open ground west of the prison walls, within a short distance of the jetty and preparatory school. All knew their purpose.

The condemned prisoners had all been kept in solitary confinement since sentencing and, despite repeated requests for visits by a priest, none was permitted. The only concession was that as they were assembled that final afternoon inside the cell block they had five minutes together in which to talk and compose themselves.

Mrs Loie was sobbing. At this moment it was the Indian, the Sandhurst-trained Captain Ansari, who spoke to them, giving an impromptu pep talk. Clearly and calmly he asked them to die bravely. This officer, who had a pre-war reputation within his regiment for being “difficult”, now again expressed the sentiments of total loyalty to the Allied cause. Anderson was told that the essence of what he said was as follows:

Everybody has to die sometime. Many die daily from disease, some suffer painful, lingering deaths. We will die strong and healthy for an ideal; not as traitors, but nobly in our country’s cause. We cannot now escape the enemy’s sword, but no one should give in to tears or regrets, but instead face the enemy with a smile and die bravely.

After these words of encouragement Wong Shui Poon, who had worked at St Paul’s College, said prayers. They were then roped together in groups of three with hands tied behind their backs and, escorted by Japanese and Indian guards, were led to the prison’s administrative compound where they were put into the “death bus” for the short drive to the place of execution. The blinds were pulled down before it drove out of the gates ahead of two Japanese staff cars.

At the time, being aware of the sentences, I recorded:

29 October, 1943

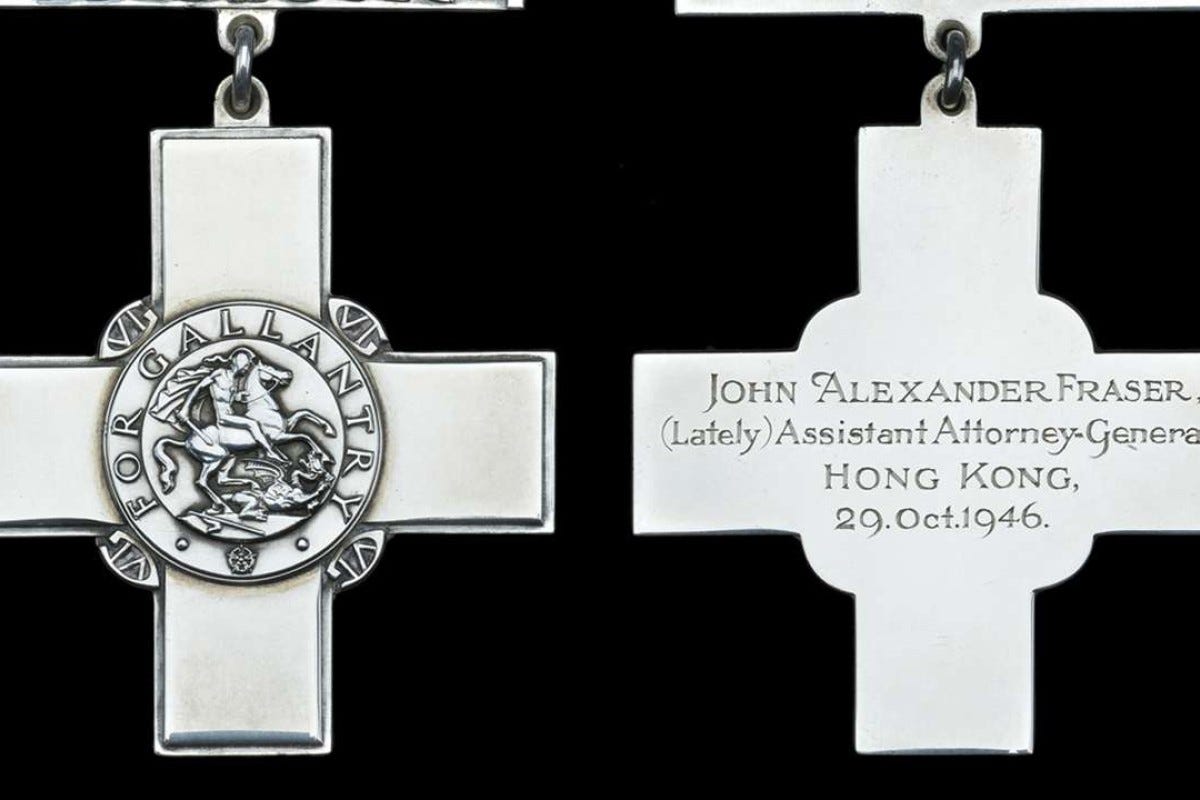

In view of recent rumours about supposed sentences imposed on the European prisoners in gaol an incident which happened this afternoon has upset everybody.... At about 2.00 pm a big, light brown car flying a military flag went into the gaol. It contained three Japanese civilians .. . behind came another car. ... A few minutes later the big prison van left the prison with three Indian guards standing on the step at the rear ... it was followed by the two cars.... As it made its way slowly along the road to get round the prison comer it passed a few internees who heard a European voice from the van call, ‘Good bye’. I believe it may have been Fraser or Scott. . .. When the van arrived at the wharf other people saw about thirty prisoners, and what they swear to be three Europeans amongst them, being marched by guards along the short distance to the execution ground.

There they were lined up in single file and told to sit down while guards blindfolded them. Among the Japanese officials watching were Kogi, Yamaguchi, his second-in-command Imiaye, and a doctor. Hirano was standing with drawn sword by the graves waiting for the first trio to be led forward the last few paces.

It was Ansari, Scott and Fraser. Ansari knelt, hands still bound behind his back, eyes bandaged. Without prompting he leant forward to expose his neck, his face a mere inch or so from the sand. Hirano raised his arms, the sword slanted back above his head, glinting brightly in the sunlight. He glanced towards Kogi, who nodded.

A momentary pause as he sighted on Ansari’s neck, then down swept the blade in a silent, silver blurr. It was an expert’s stroke, removing the head with a dull thud. Blood from severed arteries spurted up over Hirano’s polished field boots and soaked the bottom of his trousers. His sword had lost its shine. He stood motionless while the body and head, which had not fallen into the pit, were pushed in. Now it was Scott’s turn, then Fraser, then ...

Hirano began to tire and lose concentration quite quickly, so others took their turn, including Sahara and Takiyawa. The butchery became even more cruel and bloody as some victims moved, or inexpert swordsmen only partially severed a head. Some waiting prisoners who had broken down had to be dragged forward squirming and squealing and forced to kneel.

Wong Shui Poon was struck by Sahara, whose blow only wounded him so that he lay shrieking in agony with his life blood pouring from his open neck. Still alive he was booted into the grave where he lay crying piteously until Sahara leaned over to thrust the point of his sword into his stomach.

Takiyawa made a similar mess with Kotewall. He also was thrown in while still obviously not dead. This time Takiyawa apparently finished him off with revolver shots.

It is of interest to record at this point that Takiyawa’s eventual fate was perhaps appropriate. After the Japanese surrender he was seized, half-drowned, then lynched by a Chinese mob before being hanged, still alive, from the Star Ferry terminal and left to rot.

According to Anderson’s account the nightmare continued for over an hour. God alone knows the mental torment and terror those near the end of the line had to endure before their turn finally came.

At last the graves were filled in by the Indian guards. Then the Japanese, who had been laughing and joking throughout, suddenly became serious. Water was sprinkled on the soil, while all the Japanese bowed deeply before departing.

Despite it being such a botched job it called for a rowdy celebration that night. Anderson again:

No Japanese officer appeared that evening to supervise . . . the roll call and search of prisoners . . . but that night, emanating from the Japanese officers’ gaol quarters, there were the sounds of loud voices, laughter and gramophone or radio music, and the rabble as from a drunken party.

The next day -

in the prison workshop revolvers were cleaned and bent swords were straightened and sharpened.

This excerpt from PRISONERS OF THE TURNIP HEADS: Horror, Hunger and Heroics, Hong Kong, 1941-1945 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

The Brutality of the Japanese was terrible.