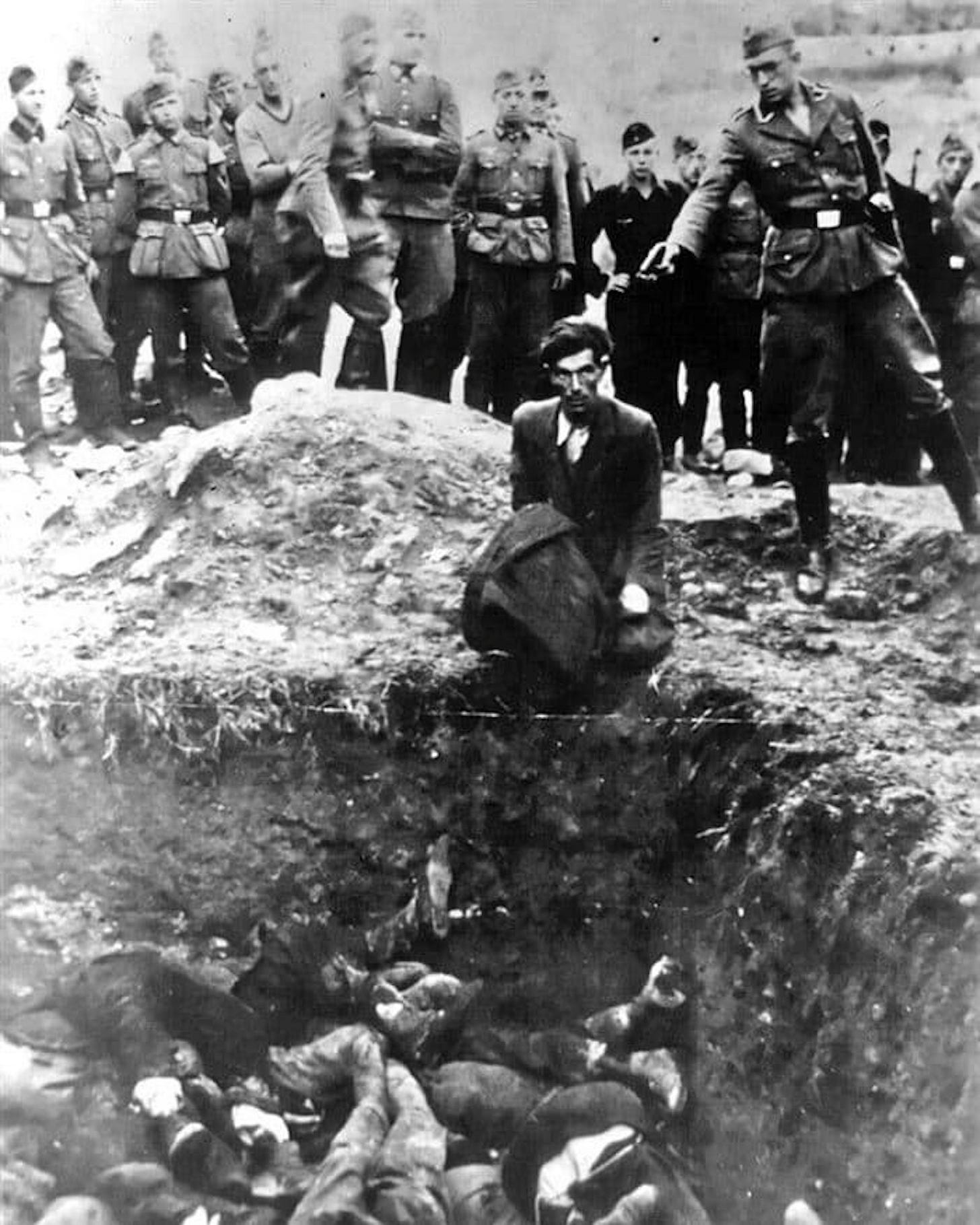

The holocaust is uncovered

7th October 1943: As the Red Army reoccupies the Ukraine the enormity of Nazi crimes against the Jewish people is difficult to comprehend

The Soviet Army continued to press hard against the retreating Germans on the Eastern front. As they advanced, everywhere they found the devastation wrought by war and the effects of the German “scorched earth” policy. They were discovering the many individual tragedies and longstanding sorrows amongst the surviving population.

…the old man was forced to dig his own grave. He had to die alone. There were no other Jews alive in the spring of 1943.

But a deeper level of devastation was also apparent, a devastation that time could not heal. The truth about the murder of entire Jewish communities was now being discovered. It was a truth that sat uneasily with the Soviet outlook, where no single group could be said to have suffered more than another. Yet the Germans had singled out a single group.

Later the legal term ‘genocide’ had to be invented to describe the horrors here. Vassily Grossman1, travelling with the advancing armies, did his best to put into words what this meant in human terms:

There’s no one left in Kazary to complain, no one to tell, no one to cry. Silence and calm hover over the dead bodies buried under the collapsed fireplaces now overgrown by weeds. This quiet is much more frightening than tears and curses.

Old men and women are dead, as well as craftsmen and professional people: tailors, shoemakers, tinsmiths, jewellers, house painters, ironmongers, bookbinders, workers, freight handlers, carpenters, stove-makers, jokers, cabinetmakers, water carriers, millers, bakers, and cooks; also dead are physicians, prothesists, surgeons, gynaecologists, scientists — bacteriologists, biochemists, directors of university clinics — teachers of history, algebra, trigonometry.

Dead are professors, lecturers and doctors of science, engineers and architects. Dead are agronomists, field workers, accountants, clerks, shop assistants, supply agents, secretaries, nightwatchmen, dead are teachers, dead are babushkas who could knit stockings and make tasty buns, cook bouillon and make strudel with apples and nuts, dead are women who had been faithful to their husbands and frivolous women are dead, too, beautiful girls, and learned students and cheerful schoolgirls, dead are ugly and silly girls, women with hunches, dead are singers, dead are blind and deaf mutes, dead are violinists and pianists, dead are two-year-olds and three-year-olds, dead are eighty-year-old men and women with cataracts on hazy eyes, with cold and transparent fingers and hair that rustled quietly like white paper, dead are newly-born babies who had sucked their mothers’ breast greedily until their last minute.

This was different from the death of people in war, with weapons in their hands, the deaths of people who had left behind their houses, families, fields, songs, traditions and stories. This was the murder of a great and ancient professional experience, passed from one generation to another in thousands of families of craftsmen and members of the intelligentsia.

This was the murder of everyday traditions that grandfathers had passed to their grandchildren, this was the murder of memories, of a mournful song, folk poetry, of life, happy and bitter, this was the destruction of hearths and cemetries, this was the death of the nation which had been living side by side with Ukrainians over hundreds of years ...

Khristya Chunyak, a forty-year-old peasant woman from the village of Krasilovka, in the Brovarsky district of the Kiev oblast, told me how Germans in Brovary were escorting a Jewish doctor, Feldman, to be executed.

This doctor, an old bachelor, had adopted two peasant orphans. The locals were very fond of him. A crowd of peasant women ran to the German commandant crying and pleading for Feldman’s life to be saved. The commandant felt obliged to give in to the women’s pleas. This was in the autumn of 1941.

Feldman continued to live in Brovary and treat the local peasants. He was executed in the spring of this year. Khristya Chunyak sobbed and finally burst into tears as she described to me how the old man was forced to dig his own grave. He had to die alone. There were no other Jews alive in the spring of 1943.