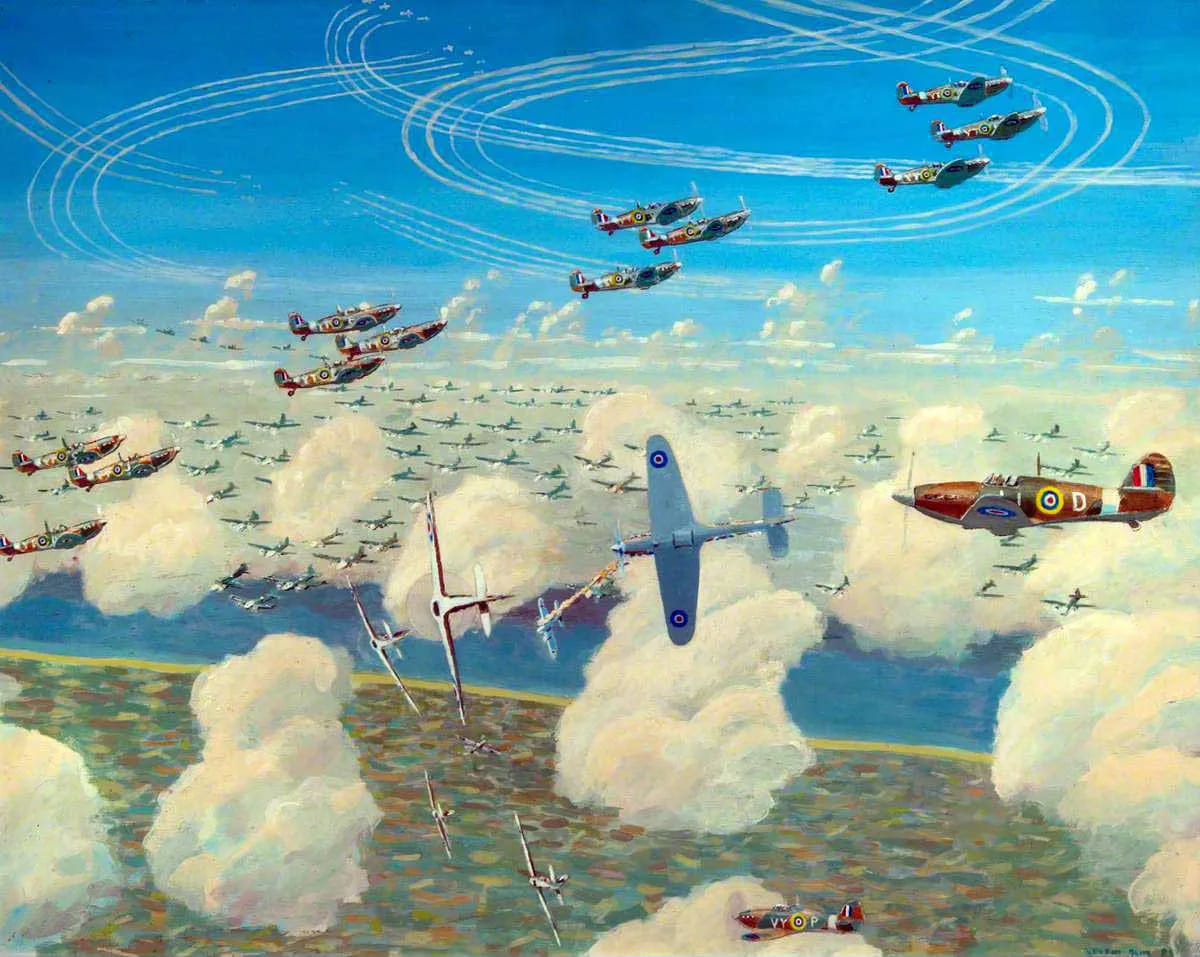

Fighter Pilots in 1940

A selection of first-hand accounts from the men who fought the 'Battle of Britain'

A Yankee in a Spitfire

28th July 1940: An American pilot volunteers for the RAF - and describes his experiences when he starts flying ‘the world’s deadliest fighter’

To myself, who had been instructing for the last year and a half in trainers of forty horsepower that cruised at sixty miles per hour, this was such a change that there just didn’t seem to be any connection with my former flying. The first time I took a Spitfire up, I felt more like a passenger than a pilot. However, I began to get used to the speed after a few hours. I practiced acrobatics mainly at first, to get familiar with the behavior of the airplanes.

In doing this I got my initiation to a new factor, which limits a pilot’s ability to maneuver at high speeds. This factor is known as the ‘black-out’ - no connection with the black-out of cities at night.

Exhaustion takes its toll

7th August 1940: Relentless days of being on alert - and flying several sorties every day - has fatal consequences for RAF fighter pilots

I called him more urgently. ‘Red three - what the hell’s the matter. Wake up Red three! Red three! Wake up!’ He continued to roll to the left and dive. The speed was mounting to the high 400s. In a few seconds I would have to break off or hit the speed of sound, which could break up the Spitfire. Obviously Mackenzie had gone to sleep. They were all so tired it was amazing how they kept awake.

‘Shot down and in the drink’

23rd August 1940: A Hurricane pilot describes the experience of baling out of a burning plane, hoping to be rescued from the English Channel

I had various problems to deal with. First of all I had to get rid of my parachute. It was difficult because I was badly burnt. Next I had to blow up my life jacket. I got hold of the rubber tube over my left shoulder but when I blew into it, all I got was a lot of bubbles. It had burnt right through. By now my face was swelling up and my eyesight was bad because my swollen eyelids were closing up. The distant view of England, which I could see a few miles away, was blurred but I started to swim vaguely in the right direction.

Head on Attack

18th September 1940: A Hurricane fighter ‘ace’ participates in a blunt confrontation to disrupt a daylight bombing raid on London

The familiar stomach-clenching tension and surging wave of excitement. Another check around. Gun-sight on? Gun button to ‘Fire’? Plug pulled and 1,850 revs? Everyone jostling and hopping about like mad and squashing together to position themselves for a decent shot. On the right of the formation, I was acutely aware of Hurricanes massing and swaying to my left. Bursting ack-ack, larger puffs now, marching in silent strides toward us. The Heinkels growing in size like characters in a cartoon film. Any moment! Some Hun fighters wheeling away to the north, getting round behind us. Watch those blighters, for God’s sake! Everyone bunching. Careful'.

Exiting a burning Spitfire

25th October 1940: Until modifications were made to the canopy, it was often an ordeal to bale out from the early Spitfires

We peeled down in the bounce and I homed in on the leader. I was just getting in to maximum range of about 500 yards when they saw us and my target bunted down into a steep dive. Since hopefully the rest of B flight following me down had selected their victims, I stuck with my 109 and slowly got more into shooting range. We were creaming downhill and I could feel the high speed buffeting on the elevators and the ailerons stiffening up. I was considering whether to open fire or get closer in when all hell broke loose.

Spitfires are still fighting the Battle

21st November 1940: RAF fighters are still intercepting Luftwaffe intruders in the south of England

I feel excitement. The same as the hunter must feel as the field gets towards the end of the chase. Never went much on this hunting lark myself. Seems a bit one-sided to me. Chasing German aeroplanes is another thing entirely. I peer ahead through the spinning disc of the airscrew and steady myself down. If we’re sensible and do the job carefully and properly then both these Huns are cold meat. They haven’t seen us.