'The Quiet Heroes'

30th November 1940: The story of how an Atlantic Convoy was massacred by a U-boat Wolfpack

Captain Bernard Edwards spent 37 years at sea with the Merchant Navy, commanding ships that traded worldwide, before retiring to pursue his second career as a naval historian. He first went to sea at the age of seventeen in 1944 as a cadet with Clan Line Steamers - so he worked alongside men who had survived the most lethal years of the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’. And the U-boats were still fighting the war in 1944. So his work is informed by a deep understanding of the perils faced by the Merchant Navy.

This excerpt is unusually long to include a complete episode from The Quiet Heroes, British Merchant Seamen at War. This volume, just one of several that Edwards wrote about the war at sea, focuses on the early years of the Battle of the Atlantic. This particular battle was fought during what the U-Boat commanders called the Die glückliche Zeit - the ‘First Happy Time’. The door was wide open for the most resolute of the U-boat commanders to make a name for themselves - to win medals and to be treated like a film star when they returned to Germany. Both the Royal Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy were hopelessly stretched as tactics and strategy were being developed, and the signals intelligence, which was to transform the campaign eventually, was still very underdeveloped:

Even before HX 901 sailed from Halifax, the Admiralty had evidence to suggest that the route of the convoy had been leaked to the Germans by sources in Canada. It can, perhaps, be understood why this knowledge was withheld from the merchant ships, but there can be no conceivable excuse for not changing the route after sailing. This was not done, and the consequences were dire, for Admiral Donitz had some of his best men at sea.

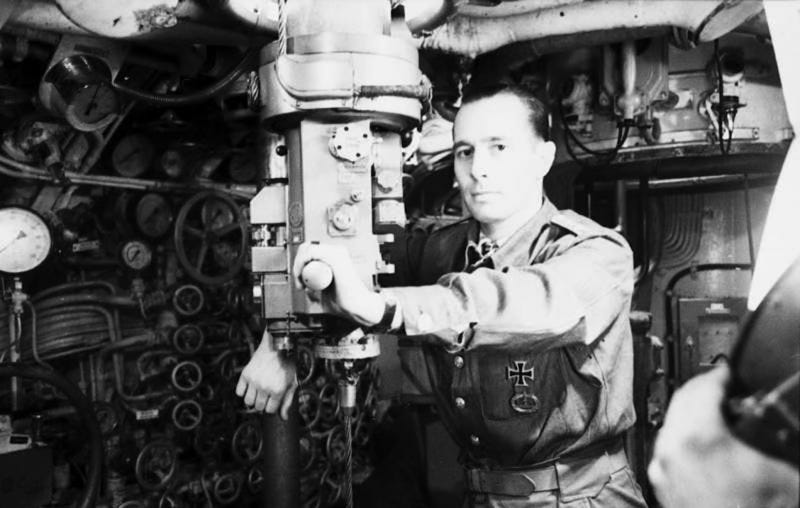

While HX 90 was reeling under the storm of 24/26 November, a thousand miles to the east the alerted U-boats were setting up an ambush. Forming up in an extended north-south line in the path of the convoy were the top-scoring ace Otto Kretschmer in U-99, Gunther Prien, idol of the German public, in U-47, Herbert Kuppisch in U-94, Otto Salman in U-52, Gerd Schreiber in U-95, Hans-Peter Hinsch in U-140, Wolfgang Luth in U-43 and young Ernst Mengersen in U-l 01. Weather conditions for the projected ambush were almost perfect, with a force 4 to 6 wind giving waves high enough to make the trimmed-down boats difficult to see, while not seriously impeding their progress. Furthermore, visibility after dark was excellent, bright moonlight until about 2000, and brilliant Northern Lights throughout the night. Unknown to the U-boat commanders - or perhaps it was - they were to be handed yet another great advantage.

In accordance with current Admiralty practice, HX 90 was due to exchange escorts with the west-bound convoy OB 251 on the morning of 2 December in longitude 17 degrees west, or 250 miles west of Ireland. HMS Laconia was to return westwards with OB 251, while the destroyers Vanquisher and Viscount, the sloop Folkestone and the corvette Gentian would leave OB 251 and take over the shepherding of HX 90 to British waters. As the two convoys were routed to pass on parallel and opposite courses at about 90 miles apart, the changeover of escorts could not be simultaneous, but it was hoped the gap would be minimal. At best, this was an arrangement fraught with danger; in the event, it turned out to be a disaster for HX 90.

At 0700 on the morning of 1 December, with HX 90 maintaining steady progress to the east at 9.5 knots, the Belgian ship Ville D’Arion developed steering gear trouble and dropped out of the convoy. This was a common enough occurrence in any convoy, but on this occasion the straggling of the Belgian ship in daylight was to set in motion a tragic and bloody train of events.

Throughout the previous night Kapitanleutnant Ernst Mengersen, in U-101, had been scouting ahead of the wolf pack, but had made no sighting of the convoy, which was actually to the south of his search area. After dawn on the 1st Mengersen decided to try his luck to the south-east and in doing so completely missed HX 90. The convoy had already crossed ahead of him and was out of sight over the horizon by the time he reached its latitude. Unfortunately for HX 90 - and providentially for Mengersen - in the afternoon he came up with the Ville D’Arion, which was again under way and steaming after the convoy at full speed. Mengersen tucked his boat in behind the Belgian ship and sent a sighting report to the rest of the pack.

The Ville D’Arion, with U-101 in close attendance, rejoined HX 90 at 1700 on the 1st at the same time as the Laconia said her farewells and left to join Convoy OB 251. The weather was fine, with the wind blowing west-south-west force 6, and darkness was drawing in. HX 90 was now steaming on an east-north-easterly course at 9.5 knots, without escort and without any naval control, other than that exercised by the Commodore in the Botavon. The opportunity was too good to miss and Mengersen carefully manoeuvred U-101 into position on the starboard side of the convoy and waited for the moon to set. At 2015 he fired a fan of three torpedoes, hitting first the 8826-ton British tanker Appalachee and one minute later the 4958-ton Loch Ranza. The third torpedo missed.

The convoy was now less than 300 miles to the west of Ireland and heavy rain had begun to fall. The explosions of Mengersen’s torpedoes were heard on the bridge of the Botason and confused lights seen in the direction of the starboard wing of the convoy, some 3 miles off, but no SOS messages were picked up or distress rockets seen. The Commodore, who had not been on the bridge at the time of the explosions, wrongly concluded that the sounds heard were thunder and the lights were signals between ships which had come near to colliding in the rain. He took no action.

Out on the starboard wing of the convoy, the Appalachee was sinking, while the Loch Ranza, herself damaged, was picking up survivors from the tanker. Both ships fell back into the darkness as the convoy continued on its unsuspecting way. Mengersen, who may not have been aware that HX 90 was now completely unescorted, had withdrawn to a safe distance, but was still in contact with the convoy.

We were like a helpless flock of sheep in a narrow lane with a dog on each side.

At 0100 on the 2nd, HX 90 altered course to approach the pre-arranged rendezvous with the escorts coming from OB 251. Thirty minutes later the Ville D’Arion again experienced a steering gear fault and once more prepared to drop astern. In doing so, she hoisted the customary ‘not under command’ signal of two red lights in a vertical line. However, these lights were not dimmed, as they should have been in wartime, and were in fact so bright that they could be seen by every ship in the convoy. If any of the U-boat wolf pack, called in by Mengersen, had any doubts about the position of the convoy, they were soon dispelled by the Ville D’Arion’s lights. At 0210 Gunther Prien, in U-47, put a torpedo into the Belgian ship and she sank quickly, taking with her the brilliant marker lights and, unfortunately, all her crew. But the damage had been done. The position of the unprotected HX 90 had been revealed to all and the wolf pack was moving in for the kill.

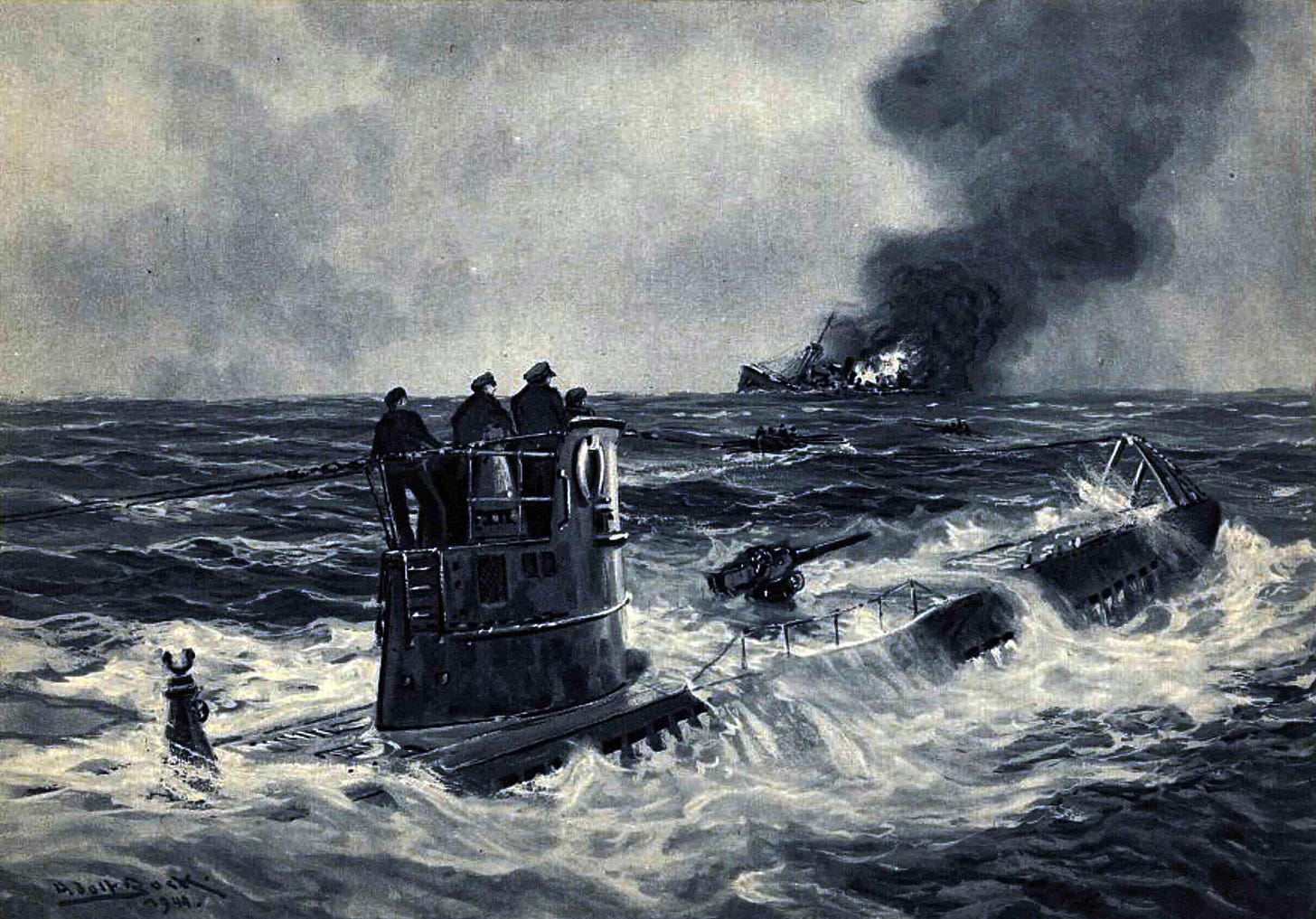

A massacre followed. The U-boats, unrestrained by the danger of retaliation, their helpless targets now illuminated by the Northern Lights, slipped in among the slow-moving columns of merchantmen and ranged up and down on the surface, torpedoing at will and using their deck guns when their tubes were empty. The convoy’s only defence lay in a series of emergency turns, by which it was hoped to spoil the enemy’s aim. Captain Issac, of the Commodore’s ship Botavon, was later to say: ‘I could not keep track of all the emergency turns as sometimes we had barely finished one when we had to go off again. We were like a helpless flock of sheep in a narrow lane with a dog on each side.’

In hindsight, it might have been wiser for the unescorted convoy to scatter at the first sign of a concerted attack, rather than stay bunched together sharing each other’s agony. Most certainly Captain Alexander Hughson, in the Lady Glanely, would have been well advised to break away on his own. He commanded a powerful motorship, only two years old, and under pressure she would have been capable of 15 knots, perhaps more. But the discipline of the convoy, instilled into the merchant captains by dogmatic naval theorists over two years of war, was too great. Hughson continued to hold position as leader of the port wing column, with his engine ticking over at little more than half speed.

Just after 0300 Ernst Mengersen, having reloaded his tubes, positioned U-101 abreast of the leading ships on the port side of the convoy. At 0320 the Lady Glanely moved into his sights and he fired. The torpedo hit the British ship squarely amidships. Eight minutes later Captain Hughson ordered his wireless operator to transmit the SSSS signal and then fired white distress rockets from the wing of the bridge. Mengersen, still on the surface, and able to aim and fire at his leisure, now torpedoed the 8376-ton tanker Conch, next ship astern of the Lady Glanely. Then he turned his sights on the 3862-ton steamer Dunsley, last ship in the column.

On the bridge of the Dunsley, her master, Captain J. Braithwaite, had heard the explosion ahead and seen the rockets arc up from the stricken Lady Glanely. He immediately altered course hard to starboard and, in doing so, avoided Mengersen’s third torpedo. Braithwaite then made a very brave and humane decision, one which was contrary to the convoy rules, but in true Nelsonian tradition. Ignoring the obvious presence of the U-boats, he steamed at full speed for the position of the Lady Glanely, hoping that he might be able to snatch some survivors from the water. At 0350 the lifeboats of the Lady Glanely, which had by then sunk, were sighted and Braithwaite rang for slow speed. Twenty minutes later, the Dunsley was approaching the boats with boarding nets over the side, ready to pick up survivors. Her efforts came to naught, for at this point U-47 intervened.

Braithwaite, occupied in manoeuvring his ship close to the Lady Glanely’ s lifeboats, was informed of the sighting of the U-boat. She was on the surface half a mile off the Dunsley’ s port beam and was clearly visible in the flare of the Northern Lights. Prien opened fire with his 88mm deck gun and Braithwaite, not a man to be intimidated, ordered his 4-inch gun’s crew to return the fire. The fight was predictably one-sided. Although the Dunsley’ s gunners claimed a hit on the U-boat, the ship was hit five times and caught fire. Reluctant though he was to leave the Lady Glanely’ s lifeboats, Braithewaite’s first duty was to his own crew. He aborted the rescue mission and, presenting his stern to U-47, he steamed away at full speed, zig-zagging to avoid the shells still bursting around him. With the attack on the convoy rising to a fierce crescendo, there could be no more help for the men of the Lady Glanely. When the destroyer Viscount and a Sunderland flying boat searched the area on the morning of the 3rd the lifeboats had disappeared. No one, it seems, will ever know what happened to those thirty-one merchant seamen on that terrible winter’s night in the North Atlantic.

The destruction of Convoy HX 90 continued. At 0515 the Liverpool-registered steamer Kavak was torpedoed and blew up. Seconds later the 1586-ton Tasso was also sunk, while the Goodleigh, sister ship to the Lady Glanely, was the victim of a savage attack by two U-boats. Gunther Prien, who had sealed the fate of the survivors of the Lady Glanely by opening fire on the Dunsley, fired the first torpedo at the Goodleigh. She was hit on her starboard side directly under her bridge, which was partly destroyed by the explosion. With his ship settling ominously, Captain Quaite, who was injured, gave the order to take to the boats. While this operation was in progress, Otto Kretschmer, in U-99, approached the crippled ship and added three more torpedoes, the last of which caused the Goodleigh’ s 4-inch magazine to explode. But the British ship had a full load of timber on board and despite her terrible wounds, she remained afloat for for several hours, allowing all her crew, with the exception of the chief officer, who was probably killed in the attack, to get away in the boats. Later in the morning they were picked up by the destroyer Viscount and landed at Liverpool on the 5th.

The Vice Commodore’s ship Victoria City, which had dropped out of the convoy on 26 November due to the bad weather, was never seen again and it is believed she was sunk by Hans-Peter Hinsch in U-140. Wreckage identified with her was washed up on the Irish coast on 8 December, but of her forty- three crew members there was no trace. HX 90’s escort force finally arrived as the sun was rising on the morning of the 2nd. The ragged remains of the convoy reformed and continued on its way eastwards. But the agony was not yet over for the remaining merchant ships, now labouring in a south-westerly gale. A far-ranging Focke-Wulf Condor sighted the convoy, and at 1000 came in to the attack, bombing and sinking the 4360-ton W. Hendrick, and wounding two men on board the Quebec City with machine-gun fire. That afternoon Otto Kretschmer and Herbert Kuppisch returned, and despite the efforts of the hard-pressed escorts, sank the 6022-ton Stirlingshire and the Norwegian ship Samanger of 4276 tons. Later, after dark, Kuppisch came back for what would be the final assault on the convoy, sinking the 6725-ton Glasgow ship ‘Wilhelmina.

When it was all over, the reckoning could be done. Convoy HX 90 had been under almost continuous attack for twenty-six hours, most of this time completely unprotected by the Royal Navy. A total of eleven ships of nearly 60,000 tons had been lost and three other ships damaged. For the U-boats, who apparently suffered no casualties, it was a cheap victory, and a victory of the first magnitude. For the merchant seamen who survived it had been a fearful nightmare they would have to live with for the rest of their lives. For the dead, there was nothing but a cold, unmarked grave.

© Bernhard Edwards 2003, ‘The Quiet Heroes, British Merchant Seamen at War’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.