Last stand on the Dunkirk perimeter

31st May 1940: The Coldstream Guards are determined to fight to the last man to hold off the Germans - only one badly injured officer gets away

The men who were evacuated from Dunkirk were saved not just by the sailors sent to rescue them but by the many men who formed the rearguard, who fought to the death to prevent the Germans from breaking through.

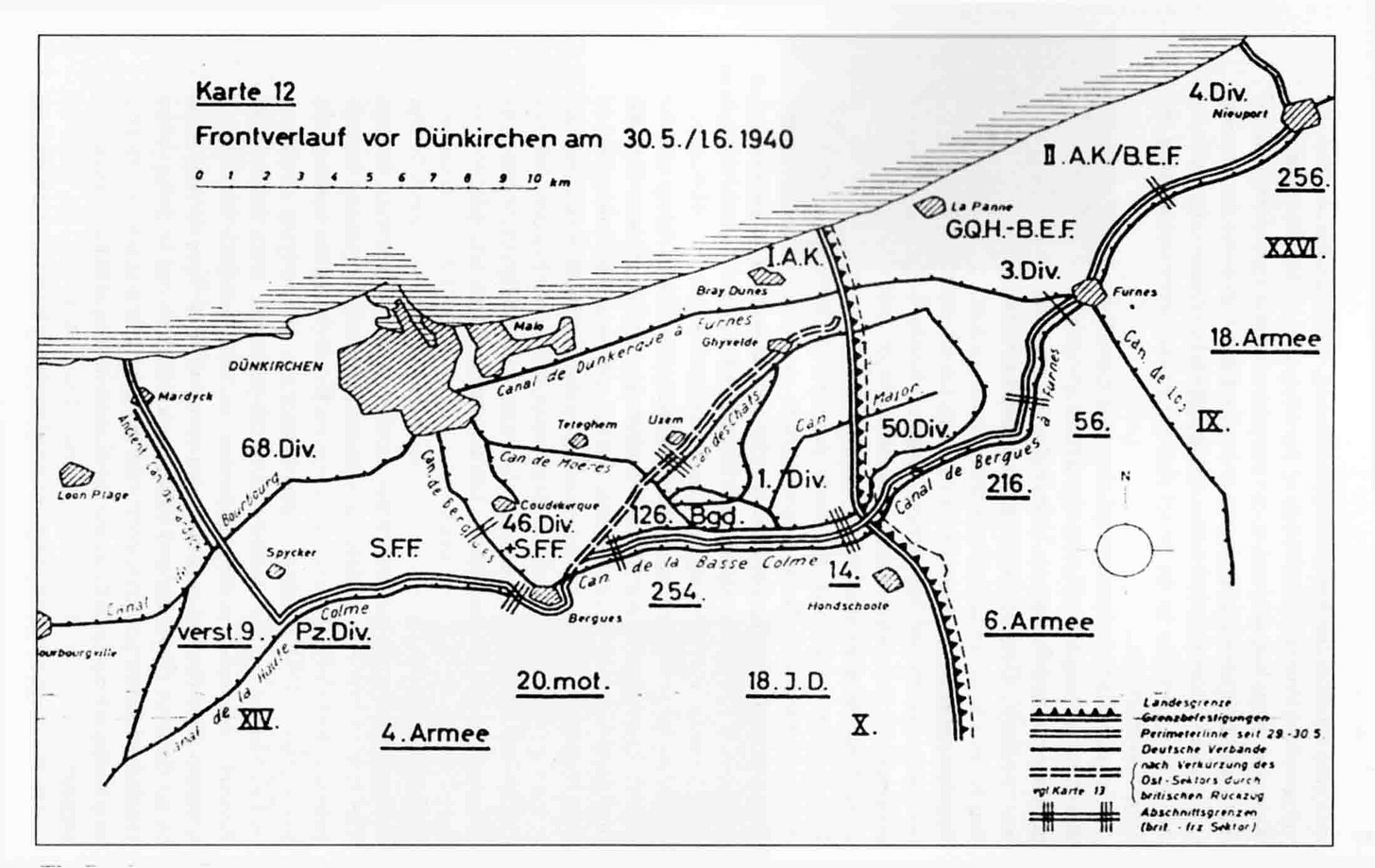

Lieutenant J. M. ‘Jimmy’ Langley (1916-1983) was with No. 3 Company, 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards. He wrote a rare account of their action on the Dunkirk perimeter in Fight Another Day1. His Battalion defended a canal overlooked by a cottage, which they converted into a defensive position. The surrounding land had been deliberately flooded.

Langley describes the fighting in a very understated style, which sometimes obscures details. He describes how an officer in a different regiment on their flank was threatened with being shot if he withdrew, and was apparently shot by Guards’ officers when he attempted to do so.

The four surviving officers in his company had a drink together on 31st May, during a lull in the fighting. Of the four, only Langley would survive the next 24 hours. He was sent out to report on the situation of the other officers in the battalion, No 1 Company was in front of them:

I returned to report that the only officer left was Ronnie Speed who had only joined the battalion a few weeks earlier and that he proposed to withdraw on to us. Angus [Major Angus McCorkodale, now commanding the Battalion] replied quietly ‘Is your flask full?’ I told him it was nearly empty. ‘Take mine and make Ronnie drink all of it. If he won’t or still talks of retiring, shoot him and take command of the company. They are not to retire.’

Ronnie was looking miserable, standing in a ditch up to his waist in water and shivering. I offered him Angus’s flask and advised him to drink it, which he did. ‘You are not to retire. Do you understand?’ He nodded, but was killed half an hour later when the enemy attacked and drove what was left of No 1 Company back on to us.

My memory of the next few hours is disjointed. Someone cooked a delicious chicken stew over a fire behind one of the outhouses and I can remember wolfing it down with white wine. The Germans tried to bring up some guns in front of us but they were knocked out by the Boyes anti-tank rifle. An old woman suddenly appeared asking for shelter and I told her to go to hell. Then I felt deeply ashamed, called her back and apologized, offering her shelter in one of the rooms at the back of the cottage.

One of my section commanders asked what he should do with all the unopened tins and I was engulfed by a wave of hatred for the Germans. Why should these bloody bastards invade other people’s countries, destroy their homes, villages and towns, machine-gun and bomb them on the roads, and take what did not belong to them? Well, they were not going to get any of our food. ‘Destroy them.’ ‘How?’ came the query . ‘Stick a bayonet into every tin.’ We indulged in an orgy of destruction. If the Huns were not going to eat our food they were not going to cook their own. In a rage I smashed the cooking stove with a hammer.

We got the Brens back in the attic and dealt with the Germans who were advancing along the canal road. We managed to set three lorries on fire, which effectively blocked the road.

Later - how much later I do not know - I went down to see how Angus was. He was lying on the top of the trench, half curled up, still in ‘service dress’ , Sam Browne breeches, green stockings and brown shoes but he no longer wore his famous papier mache steel helmet. A dead guardsman was lying beside him. I told him I thought we could hold the enemy from the cottage but I am not sure he understood. ‘I am tired, so very tired,’ he said and then, with a half smile, he rallied and gave me his last order. ‘Get back to the cottage, Jimmy, and carry on.’

The Germans got into a cottage on the other side of the canal where part of the roof and front had been blown away. They poked a machine-gun through the tiles, but we saw it and blasted them away with a Bren gun before they could fire. In one Bren gun the firing pin had melted rendering it useless and when the firing died away I ordered the other gun downstairs where it would be more effective if the enemy tried to swim the canal and rush the cottage.

I doubted if they would do this, but to show them we were still very much alive I started my favourite sport of sniping with a rifle at anything that moved. I had just fired five most satisfactory shots and, convinced I had chalked up another ‘kill’ , was kneeling, pushing another clip into the rifle, when there was a most frightful crash and a great wave of heat, dust and debris knocked me over. A shell had burst on the roof.

There was a long silence and I heard a small voice saying ‘I’ve been hit,’ which I suddenly realised was mine. That couldn’t be right; so I called out, ‘Anybody been hit?’ A reply from behind - ‘No, sir, we are all right.’ ‘Well,’ I replied more firmly, ‘I have.’ No pain, just a useless left arm, which looked very silly, and blood all over my battle-dress.

A stretcher bearer arrived and put a field dressing on my arm, removed my watch, which he later sent to my parents in England, and bandaged my head. I remember being half carried, half helped down from the loft and some time later being put into a wheel barrow. Later splints made out of a broken wooden box were tied round my arm and I was put into an ambulance, then off we went to the beaches. No pain, only a terrible thirst. I shouted for water, but no one heard me over the noise of the engine.

For what seemed hours we bumped along, continually stopping and starting. The man above me must have been bleeding badly as the blood began to drip on to my face and I had to keep wiping it off with the edge of my blanket.

At last the door was opened. My stretcher was pulled out, a water bottle was held to my mouth. In the half light of dawn I could see sand dunes and a voice said ‘This way. The beach is about two hundred yards ahead of you.'

Langley did not make it onto the beach, he was too weak as a consequence of the injury to his arm, which was subsequently amputated by a German doctor. He eventually escaped, made his way back to England, and then played a leading role in establishing escape and evasion lines in north-west Europe.

The story is taken up in The Dunkirk Perimeter and Evacuation 19402, a comprehensive study of the battle, with many personal accounts:

Captain Jack Bowman, the Battalion MT Officer, managed to extract the remnants of Numbers 1 and 3 Company and the battalion withdrew under the cover of darkness.

Langley was evacuated in a wheelbarrow but unfortunately was refused a passage home owing to the severity of his wounds. He later escaped, minus his left arm, which had been amputated at Zuydcoote. Details of the battle reached Lionel Bootle-Wilbraham whilst he was still at Brigade Headquarters:

The Germans had outflanked No. 1 Company, having got across the canal where our neighbours had abandoned their positions. The three officers of the company had been killed ... The warrant officers and senior NCOs had been killed, including CSM Dance and Sgt Hardwick; and the leaderless company had been forced back on to No.3 Company. The men had been rallied by the officers of No.3, which had been outflanked. Angus had been killed when his bit of trench had been enfiladed.

The 35-year-old McCorquodale, whose brother married Barbara Cartland in 1936, was killed about the same time as Langley was hit. Few of the battalion got away that night and those that did were taken aboard HMS Sabre on the night of 2 June, leaving behind seventy officers and men who had been killed and another thirty-six designated as missing or prisoners of war.

© Estate of J. M. Langley 2013, 'Fight Another Day'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.

© Jerry Murland 2019, 'The Dunkirk Perimeter and Evacuation 1940: France and Flanders Campaign'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.