'Destination Dunkirk'

16th May 1940: The BEF begin to 'withdraw' as Churchill flies to Paris to learn the awful truth from the French High Command

Early on the 15th May, Winston Churchill, on his fifth day as Prime Minister, received a telephone call from the French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud:

We have been defeated... we are beaten; we have lost the battle... The front is broken near Sedan.

Churchill did his best to rally Reynaud and decided that he needed to travel to France to see for himself.

The entire French military strategy since the ‘Great War’ - building massive defensive structures on the Maginot Line and moving their best troops forward into Belgium to fight the war there - had been undone in a matter of hours. As the 15th May progressed, it became clearer that the Wehrmacht had indeed made a dramatic breakthrough. The most significant and best-equipped German Army formation appeared poised to make a direct assault on Paris.

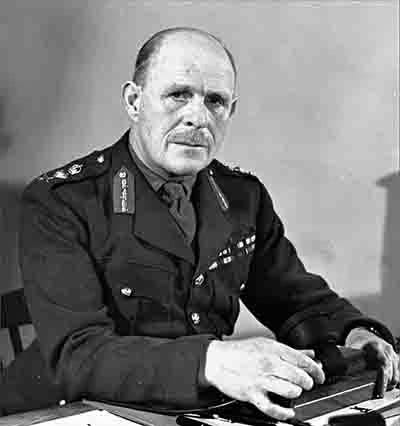

From the British perspective, the position of the British Expeditionary Force, commanded by Lord Gort VC, was suddenly very exposed. During the course of the 15th, orders went out for a withdrawal.

Gregory Blaxland was one of the youngest British officers serving in France at the time, experienced the debacle at first hand, he was evacuated from Dunkirk on 31st May. In 1973 he published a very well-received full account of the campaign, Destination Dunkirk: The Story of Gort's Army. The following excerpt takes up the story on the 16th May, soon after orders reached the British Expeditionary Force to begin a withdrawal:

The sudden news of the withdrawal was received with that resigned bafflement which British troops have their own individual way of expressing. It was known that the French had suffered something approaching a disaster on the Meuse and that the Dutch had been completely eliminated.

Yet the British themselves felt far from defeated, and it was hard to believe that it was really necessary to leave the defences on which they had worked so hard and trudge off into the blue. In many ways it was the same story as at Mons in August 1914, except that the Germans had been in sufficient number and proximity there to make their menace apparent.

The stated object now was merely to conform with the overall Allied plan, and since the extent of the withdrawal was given as no further than the next riverline, few as yet guessed that the plan devised by the master brain of Gamelin had been knocked hideously awry.

Just how far the plan was in ruins was being told to Winston Churchill by Gamelin himself while the British officers and men were being apprised of its first surprising effects upon themselves.

Churchill had arrived in Paris on the afternoon of May 16, with Generals Dill and Ismay, and had been taken to meet the political and military heads of France at the Quai d’Orsay, from the garden of which clouds of cinder-speckled smoke were rising from a bonfire made of archives.

Churchill asked about the counter plans: 'Ou est la masse de manoeuvre?’

He found Reynaud, Daladier and Gamelin standing around a situation map, consumed with dejection. Gamelin gave a brief report. The German armour had broken through on a 50-mile front and was advancing at unheard-of speed either towards the coast via Amiens and Arras or straight for Paris. Churchill asked about the counter plans: 'Ou est la masse de manoeuvre?’ With a shake of his head and a shrug of his shoulders, Gamelin answered, 'Aucune.' Churchill, in his own words, was dumbfounded.

The intended mass of manoeuvre, namely the three heavy armoured divisions, had already been capsized by problems of manoeuvre. The 1st Armoured had, on May 15, run out of petrol and been annihilated in detail on the Ninth Army’s front; the 2nd had on this same day been forestalled by the panzers in the laborious and widespread act of detraining and been scattered far and wide; and the 3rd, delayed in its concentration by the flood of refugees and defeated soldiers, had been rushed piecemeal into battle and lacerated amid a confusion of counter-orders. Railways, on which the French relied so heavily, had become the principal target of German aircraft.

The French Army was paralysed, and the High Command could do little more than gaze like a rabbit hypnotised by a stoat, as the onward flow of the panzers was plotted on the map. The hypnosis relaxed its hold as realisation slowly dawned that Paris was not the immediate objective, but the nearest reserves available were under the lee of the Maginot Line and the moving of them was a slow and vulnerable business.

Little realising the true plight of their allies or the consternation of their Prime Minister, the British withdrew methodically from their positions on the Dyle and Lasne, thinning out at last light, abandoning the forward line two hours later, and falling back through rearguards, as often practised in peacetime.

The Royal Ulsters had no difficulty in breaking contact after their two days of close quarter fighting in Louvain, which cost them little more than fifty casualties, and the 1st Grenadiers on their left were also allowed to depart in comparative peace, although various flashes and rocket signals from the ghostly houses of Louvain showed that the fifth columnists were keeping their masters informed. Aircraft came over and dropped flares, but the Grenadiers marched on unmolested.

For the 1st Coldstream on the left it was less easy. They saw the Belgians withdraw in the early afternoon and, in the flat and open country forward of Herent, their left and centre companies were constantly raked by fire, even from behind their left flank. With the aid of field gunners and Middlesex machine-gunners, heavy toll was taken of every advance, as was testified by the motionless grey forms beneath the willows by the water’s edge. But every move within these company areas was instantly scotched, except that of the carriers, which proved that they could be of as much value for the carriage of wounded and ammunition as for fire support.

The withdrawal was timed to begin at 9 and end at 11, and as the first troops came back in the half light, to the accompaniment of a crash of shells from their own guns, the Germans crossed the canal from further round the British left flank and gained entry into Herent, through which the main withdrawal route lay. There was some desperate and confused fighting as the reserve and headquarter companies tried to hold the route open, and the forward troops came back with bayonets fixed, with mortar bombs crashing around them, and with tracer bullets zipping across their line of retreat in continual streams.

There were heavy losses, bringing the battalion’s casualties to around 120, nearly all in the left and centre companies. The rearguard retained a footing in Herent and established that all survivors of these companies had passed through before falling back themselves. The Inniskilling Dragoon Guards now took over rearguard duties and were able to give succour and lifts in their tanks to many weary and battlewom Coldstreamers.

Elsewhere, the troops withdrew with only a few incidental mishaps, as for instance the loss of three carriers of the 1st Duke of Wellington’s (1st Division) on mines laid prematurely by the divisional sappers. Apart from the attack at Herent, which was made by the 19th Division, the Germans chose (as was their custom) to use the night for rest and reorganisation, and yet they must have been warned that a withdrawal was taking place by the mass of shells that came screaming over.

The medium guns of I Corps alone fired 12,150 during the night, around 150 from each gun, and this was because there was no other way of removing all the rounds that had been dumped. It was certainly a busy night for the gunners, and they were among the last to fall back behind the armoured regiments that took over rearguard duties with the coming of daylight on Friday, May 17, exactly one week after the call to battle had been sounded.

Practically every battalion of the 3rd, 1st, 2nd, and 48th Divisions now took a brief and much needed rest in that massive refuge, the Forest of Soignes, where nightingales sang their greeting. Most quartermasters succeeded in delivering breakfast, although some were thwarted by the bombing of the roads, the swell of refugees, the inadequacy of maps, or just faulty information. The retreat had begun, and one of the hardest problems it posed was to establish locations.

The pause had to be short, for the troops were still between 5 and 10 miles from the Senne, and great chaos could be wrought if the enemy’s mobile troops were to burst in among them. But except on the extreme southern flank, where the 12th Lancers were under pressure, the armoured regiments had to contend only with the occasional patrol of motor cyclists and sniping by fifth columnists. It was as well that the panzers were operating in more suitable country elsewhere.

All through the morning British troops tramped through the streets of Brussels, usually in platoon formations, with the odd limper trailing behind. There were plenty of people about, and trams were still running, in contrast with the main-line trains, in vain expectation of which a large crowd stood dejectedly outside the station. Although a few people made gestures of warmth and sympathy, most of the soldiers could feel the reproach in the gazes cast upon them from many sullen faces.

It was humiliating to come back like this after being welcomed as heroes so recently; yet it caused more resentment than shame, for the British had little sympathy with an ally who had shown no resolve to face up to the menace of Nazi Germany and whose soldiers, as observed so far, seemed to have no fighting spirit. A company of the 3rd Grenadiers (1st Division) had an embarrassing experience. After coming round a corner, they were surrounded by a rush of cheering, waving people. This made the company commander check on his bearings, and he found he had taken the wrong turning and was heading towards the German Army. He brought his men back amid a silence that could be felt by even the most weary guardsman.

© Estate of Gregory Blaxland 2018, 'Destination Dunkirk: The Story of Gort's Army'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.