The Second Battle of Narvik

13th April 1940: The Royal Navy get their revenge - and make naval aviation history - when the Kriegsmarine invasion force is destroyed

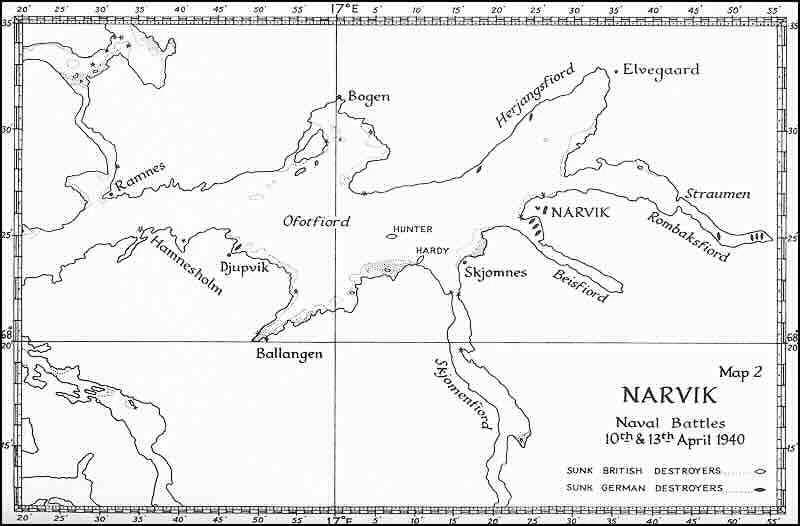

On the 10th of April 1940, a force of Royal Navy destroyers had attacked German shipping and a group of German destroyers in the port of Narvik. In the far north of Norway, Narvik was the critical centre of iron ore exports, one of the main objectives of the German invasion.

Captain Warburton-Lee had led his force down Ofot Fjord for a surprise attack on the German ships. This attack was largely successful - until he came to depart - when he discovered that he was outnumbered by other German destroyers he had not had information about. Famously, his last signal before being killed on the bridge of HMS Hardy was "Continue to engage the enemy”. Warburton-Lee was awarded the Victoria Cross:

Captain Warburton led his flotilla of five destroyers up the fjord in heavy snow-storms, arriving off Narvik just after daybreak. He took the enemy completely by surprise and made three successful attacks on warships and merchantmen in the harbour. As the flotilla withdrew, five enemy destroyers of superior gunpower were encountered and engaged. The captain was mortally wounded by a shell which hit the bridge of H.M.S. Hardy. His last signal was "Continue to engage the enemy".

Following this engagement, the Germans reinforced their forces in Narvik with three further destroyers. The Kriegsmarine now had almost half Germany’s entire complement of destroyers based many miles down a remote Norwegian Fjord. They were short of fuel and ammunition because the Norwegians had managed to sink one of their supply ships. And now the Royal Navy wanted revenge.

The British attacked again on the 13th April with a force led by the old battleship HMS Warspite, launched in 1913. Taking a battleship into the confined waters of Ofotfjord was a risk. The Germans might be short of ammunition but their destroyers all carried potent torpedoes.

On Warspite, Lt. Cmdr. W.W. Fitzroy, the ship’s air defense officer, recorded his impressions of the scene.

We belted along at high speed, with the destroyers doing magnificent work ahead of us. The roar of our 15-inch guns reverberated from the steep, snow-covered sides of the fjord, but the explosions of the enemy torpedoes when they hit the rocks were even greater.

But the launch of the Warspite's Swordfish aircraft gave the the British a very significant advantage1:

On the morning of 13th April, 1940, the Warspite, wearing the flag of Vice-Admiral Sir W. J. Whitworth, K.C.B., D.S.O., and screened by nine destroyers, passed through the entrance to Ofot Fiord, leading to Narvik, which lay some 30 miles ahead.

At 11.52, when five miles west of Baroy Island, the Warspite catapulted her aircraft with orders to reconnoitre ahead of the Force as it advanced up the fiord, and to bomb any suitable targets. The observer was Lieutenant-Commander W. L. M. Brown, R.N., the pilot, Petty Officer F. G. Rice, with Leading Airman M. G. Pacey as the air-gunner.

Low clouds formed a ceiling between the steep cliffs, and as the Swordfish proceeded up the fiord it was like flying in a tunnel.

…

The Swordfish dived to 300 feet to release its bombs The first hit the bows of the submarine. Owing to the explosion the second bomb's exact point of impact was difficult to observe, but it was either a hit or a near miss. The air-gunner raked the conning tower with a burst from the rear gun. The submarine sank within half a minute, but had had time to open fire, and damaged the tail plane of the Swordfish, making it sluggish on the controls so that the pilot had to manoeuvre gently during the rest of the flight.

At 12.40 Lieutenant-Commander Brown reported that an enemy destroyer was hiding in a bay five miles ahead of the screen (presumably hoping to remain unseen against the rocky background) in a position to fire torpedoes at the advancing Force. The leading destroyers turned their guns and torpedo armament on the starboard bow, and before the enemy could fire more than one salvo he was heavily engaged. One torpedo from the Bedouin and another from the Eskimo struck her, and in three minutes she was on fire fore and aft. Salvoes from the Warspite's guns completed her destruction.

The official account continues:

Shortly alter this action Lieutenant-Commander Brown sighted five torpedo tracks approaching the Force and gave timely warning. They passed clear and exploded against the cliffs of the fiord. Narvik lies near the entrance to Rombaks Fiord, into which three enemy destroyers were seen to retire under the cover of smoke screens. Five of the British destroyers pursued them, while others entered Narvik harbour and attacked another German destroyer, which caught fire under the combined attack and blew up later. All resistance in the harbour then ceased.

The Swordfish proceeded to reconnoitre the position in Rombaks Fiord. The Warspite was engaging the enemy, and the smoke from her exploding shells, combined with the low clouds and the steepness of the cliffs on either side of the narrow fiord, made observation and visual signalling very difficult. At 3 p.m., however, the Swordfish reported two enemy destroyers at the head of the fiord. The Eskimo engaged them, closely followed by the Forester and the Hero. The enemy replied with gunfire and torpedoes, and the Eskimo had her bow blown away. Then one of the German destroyers ran aground.

The Swordfish dropped its remaining bombs on her and she was finished off by gunfire. The other destroyer retired under the cover of smoke to the top of the fiord.

At 3.30 the Bedouin signalled that both she and the Hero had almost exhausted their ammunition and that the remaining three enemy destroyers were lurking round a corner of the inner fiord, out of sight, and in a position of great advantage if they still had torpedoes.

The torpedo menace must be accepted. Enemy must be destroyed without delay.

Vice-Admiral Whitworth replied :

The torpedo menace must be accepted. Enemy must be destroyed without delay. Take Kimberley, Forester, Hero and Punjabi under your orders and organize attack, sending most serviceable destroyer first. Ram or board if necessary.

…

When the destroyers proceeded up the fiord, however, there was no reply to their fire. The enemy had abandoned the three vessels. One had been scuttled, another was sinking, and the third was sent to the bottom by a torpedo from the Hero. This ended the main action, and the Swordfish returned to the Warspite, having been four hours in the air.

During that time it had passed back vital information about the position of the enemy ships, besides reporting torpedo tracks, taking photographs, bombing a destroyer and sinking a submarine. The total German naval forces present had been sunk without the loss of a British ship, for both the Eskimo and the Cossack (which had drifted on to a submerged wreck in Narvik Bay) were able to return with the Force.

I doubt if ever a ship-borne aircraft has been used to such good purpose as it was in this operation.

The Vice Admiral reported:

The cumulative effect of the roar of Warspite's 15inch guns reverberating down and around the high mountains of the fiord, the bursts and splashes of these great shells, the sight of their ships sinking and burning around them, must have been terrifying to the enemy,

… The enemy reports made by Warspite's aircraft were invaluable, I doubt if ever a ship-borne aircraft has been used to such good purpose as it was in this operation.

Chief Petty Officer Fred Jones was in charge of ‘B’ Turret2 aboard HMS Warspite:

For us, the Battle of Narvik begins with the order “Action stations.” The gun crews take up their positions and the turret captain reports to Control. We then hear “All guns load” and up come the gun-loading cages with a thud and out go the rammers.

The Controller barks “Salvoes” and the right gun is brought to the ready. Then “Enemy in sight” and the sight-setters chant out the range, by which time both guns are almost horizontal because of the close range.

The fire gong sounds “Ding ding,” the right gun fires and recoils as a “woof” rocks the turret. The left gun is brought to the ready as the right gun re-loads.

Sixteen rounds have been fired in the fiord and the targets either sink or blow up. Control issues the order “Check fire” and the gun crews clamber through the manhole at the top of the turret to see the damage’

Almost half of Germany’s modern destroyers had been sunk or put out of action. This was a blow just as serious as the loss of the brand new cruiser Blucher, sunk before she could ever fire a shot in anger. The Kriegsmarine had been significantly weakened in less than one week of war in the West.

But the actions in Norway were a sign of things to come. The first U-Boat had been sunk by an aircraft, days after the sinking of the light cruiser Konigsberg, the first major ship sunk by dive bombers. Around the world naval strategists were watching events with great interest, not least in the Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States Navy.

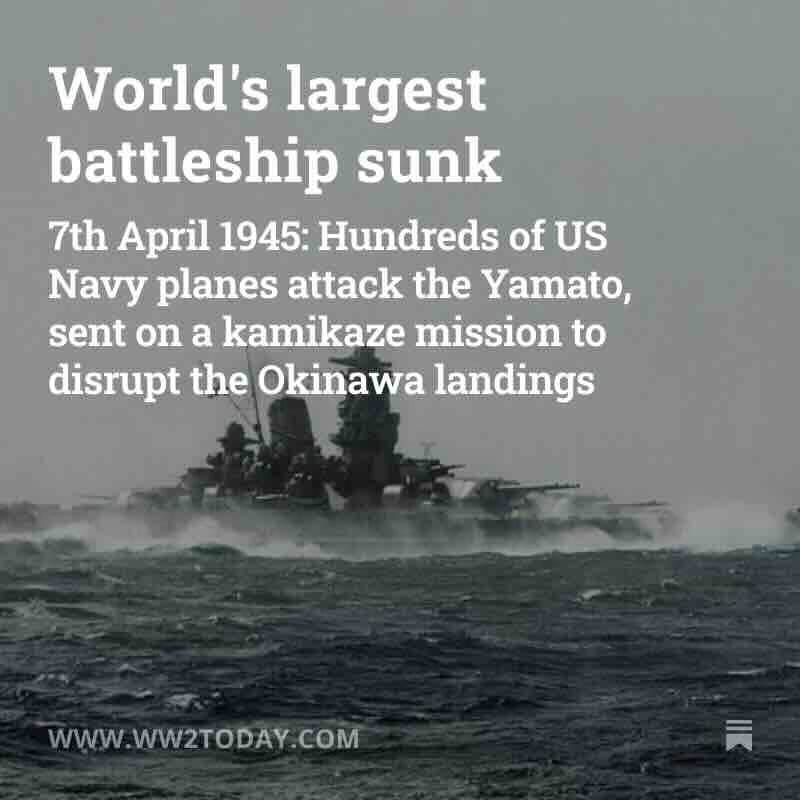

It would take more than these actions for the lessons of the transformative impact of aircraft - both land based and ship borne - on naval warfare to be fully absorbed. Sometimes those vital lessons were ignored - at peril to the naval forces enagged. The consequences could be seen almost exactly five years later with the loss of the Yamato, the most powerful battleship ever built.

And the loss of the ship Konigsberg was perhaps also a portent of wider symbolism. Almost exactly five years later the city of Konigsberg would fall. German citizens would suffer the consequences of centuries of militarism and the waging of an aggressive war of conquest.

From the Ministry of Information account of the action