'Standing Up to Hitler'

A new study that surveys the many different strands of German resistance to Hitler

Hitler believed that he had been ‘chosen’ by fate to pursue his various aggressive fantasies. There is some evidence to support this view when the many different groups and individuals who sought to counter him are considered. Norman Ridley’s very recently published Standing Up To Hitler: Resistance in Nazi Germany comprehensively reviews all of these schemes, from organised conspirators within the Wehrmacht (who had sympathisers running right up to the very top) to young students acting out of conscience. Time and again, ‘luck’ was to play a part in helping Hitler along.

The following excerpt examines events in November 1939, when two simultaneous plots against Hitler were being actively pursued. One was a conspiracy by Generals within the Wehrmacht High Command, the OKW. The other was the ‘lone wolf’ bomb plot of George Elser that came as close to succeeding as any attempt on Hitler’s life:

Poland fell within weeks and Germany found itself in a state of war with Britain and France, albeit at a distance and with little actual engagement, but the euphoria of a stunning military victory was tempered within the OKW by two factors.

The first was the evidence of SS terror that had been unleashed against the Polish intelligentsia and the Jews. Of course it was no surprise that Himmler had extended his terror campaign to Poland but it was the sheer scale of the atrocities that were committed during those first few weeks of occupation that shocked and horrified the Wehrmacht generals.

Then there was the simple fact that Germany was now at war with two nations that were significantly more powerful, both militarily and economically, than Poland and as early as October, Hitler was already making plans for ‘the final military defeat of the West’.

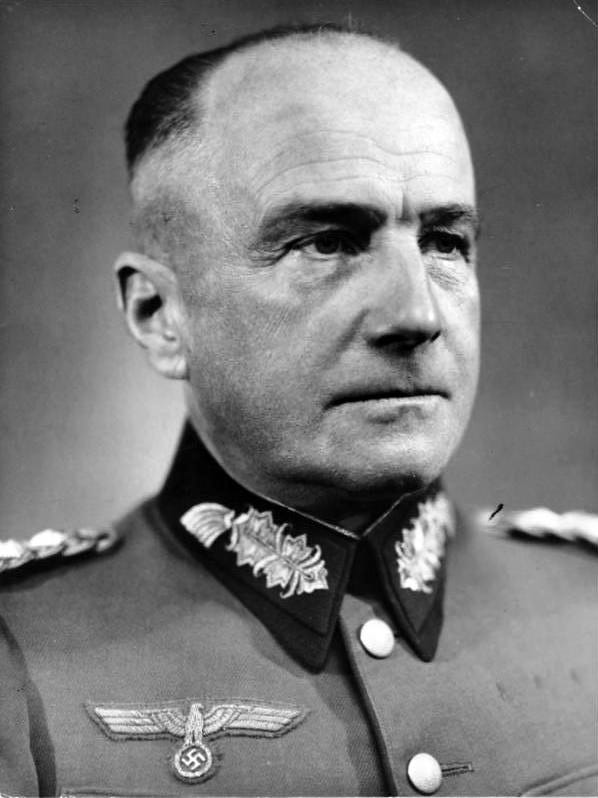

The three Army Group commanders in the west, Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, Gerd von Rundstedt and Fedor von Bock protested in the strongest terms saying that their forces were nowhere near ready to take on the Western armies. Fearing a catastrophe if Hitler went ahead with his plan, Halder kept two armoured divisions in reserve and ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Grosscurth to formulate a plan for a coup.

Lieutenant-General Karl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel and Oster, with whom he had plotted in the 1938 conspiracy, met Beck who, in turn, kept closely in touch with Goerdeler and the diplomats Ernst Heinrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker and Ulrich von Hassel. At the Auswärtiges Amt Erich Kordt drew up a memorandum outlining the ‘threatening catastrophe’ that would follow at attack in the West. ‘Never was Germany closer to chaos’, he wrote, and ‘once the furore of war is let loose, it cannot be coaxed back by reason’.

Oster was again at the heart of planning. Beck and Goerdeler were kept informed. On 5 November 1939 Brauchitsch and Halder tried to dissuade Hitler from issuing an attack order timed for seven days hence but Hitler dismissed them furiously with an insult aimed at the ‘defeatist’ OKW. Brauchitsch was subdued by Hitler’s rant and seemed to lose heart for insurrection. Beck remained committed and Oster made arrangements to procure explosives for a bomb but fate stepped in three days later when another, quite separate bomb plot almost took Hitler’s life at the Bürgerbräukellar in Munich.

… appalled by Nazi’s attack on human dignity and the mesmeric hold Hitler had over his audience.

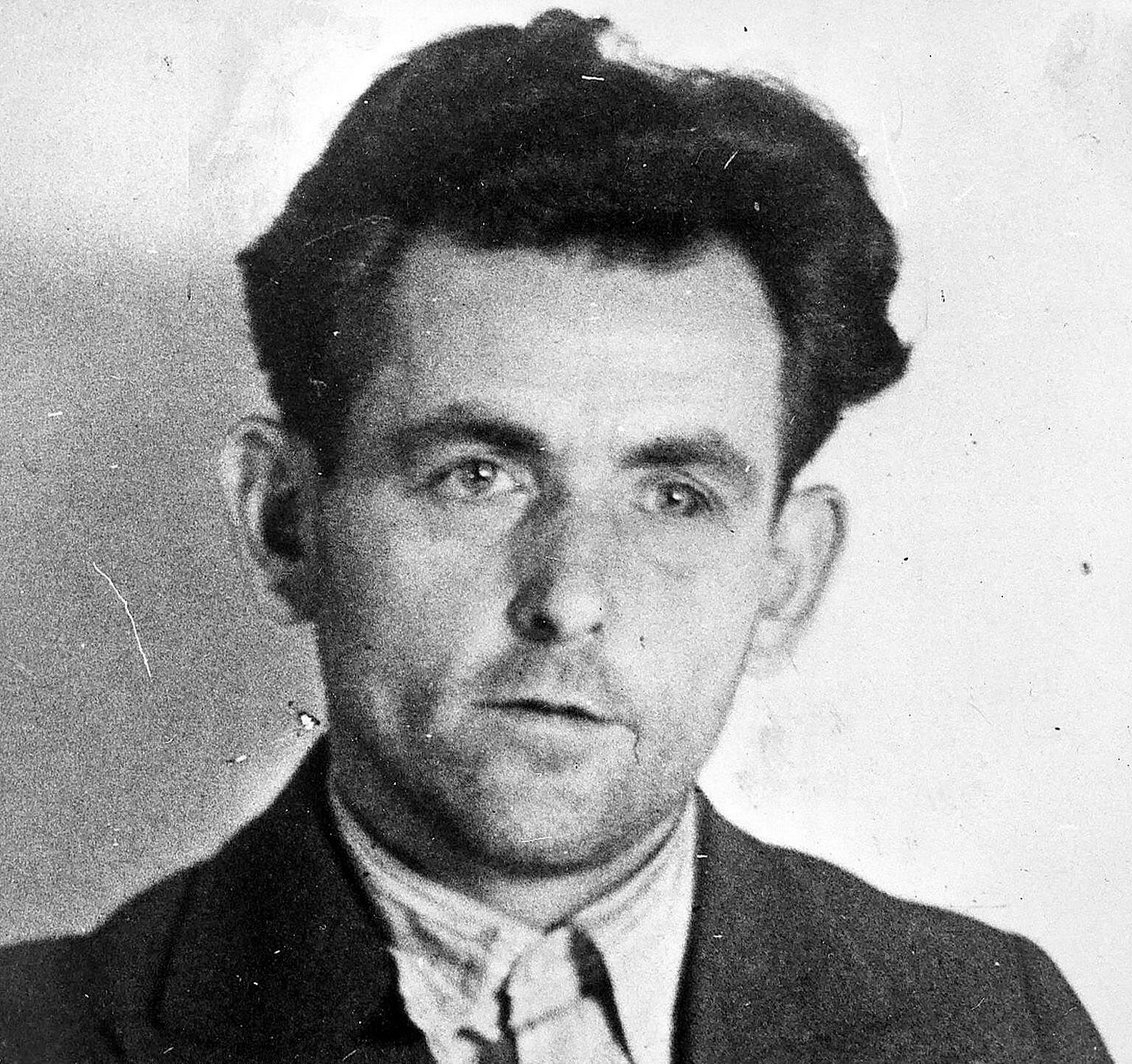

Johann Georg Elser had long been hostile to Nazism and plotted all alone to put an end to Hitler’s rule. An Einzelgänger or ‘lone wolf’ with no known friends, he had witnessed Hitler’s speech on the previous year’s anniversary of the 1923 coup attempt and was appalled by Nazi’s attack on human dignity and the mesmeric hold Hitler had over his audience. Along with many Germans he feared that war was coming closer with Hitler’s every reckless gamble and throw of the political dice and the increasing persecution of vulnerable minorities within Germany filled him with disgust. There grew within him a conviction that he must act somehow to give expression to his opposition to all that he saw around him. Right behind where Hitler made his annual speech was a load-bearing support for the balcony and heavy roof above. It did not take much imagination to see what would happen if that pillar was suddenly removed. It was not necessary to smash through Hitler’s formidable security cordon that accompanied him everywhere on his now infrequent public engagements.

Elser collected material to construct a time-bomb and moved to live in Munich permanently in August 1939. He started visiting the bierkeller every day for his evening meal and hid in a cloakroom when the place was locked up for the night. Each night he would work on excavating a hole in the main columns holding up the roof where he planned to place the bomb then in the morning he would sneak out again when the building was opened up. He installed the bomb on the night of 2/3 November and activated the timing mechanism to detonate three days later. Then he left Munich to go to Konstanz with a view to crossing the border into Switzerland.

A mere thirteen minutes …

On the evening of 8 November, there were some 1,500 people in the bierkeller to hear Hitler make his annual speech. The audience consisted mostly of many veterans of the original Putsch dressed in their old uniforms, fuelled by Bavarian ale and roused by martial music. Hitler was deep into planning for the invasion of France and had wanted to avoid the trip to Munich altogether but had been persuaded that it would be seen as disrespectful not only to the audience but to the Nazi movement as a whole if he did not go. He went but insisted on having his personal train ready for a swift overnight return to Berlin immediately afterwards.

Eager to get back to Berlin as soon as possible, Hitler started his speech half an hour early and finished at 21.07 hrs, a whole hour before it would have finished had it followed precedent. A mere thirteen minutes after he had stood down from the podium and left the room the bomb exploded bringing down the whole roof.

The pillar had been torn apart by the blast, and where Hitler had stood the entire ceiling had crashed onto the lectern and onto the surrounding rows of chairs and beer tables. The falling masonry, roof girders and wooden beams killed three people instantly and buried dozens, five of whom died after being admitted to hospital.

Elser was arrested on the Swiss border. He spent the war in various prisons and was eventually executed in the Dachau concentration camp at some time in April 1945.

The bomb inevitably banished any thought of attacking France, which was a relief for the generals but for the Oster conspirators it was a major setback. They were further disheartened and chastened on 23 November when Hitler addressed the General Staff and roundly condemned his critics over a period of several hours.

He called his audience an ‘antiquated upper class’, that had failed the German people in 1918 and was failing them again with its prophecies of catastrophe. All who stood against him would be destroyed, Hitler vowed. Only one member of the General Staff, Heinz Guderian, protested at the insults. Brauchitsch tendered his resignation which was contemptuously brushed aside.

By January 1940, Beck was again broaching the subject of a coup with Halder. More attempts were made to re-establish contact with British government officials who seemed a little more interested in what the German dissidents had to say but that was too little too late to encourage Halder who now stood firmly against any coup attempt believing that it would take a significant military defeat for Germany before the rank and file would support it.

Brauchitsch had been cowed and humiliated by Hitler’s criticism and was now in no mood to entertain any talk of insurrection. He even cloaked his loss of self-esteem by threatening to expose the plotters as traitors. When Fall Gelb was launched on 10 May 1940 and succeeded beyond all expectations, it dealt a body blow to the conspirators.

© Norman Ridley 2025, ‘Standing Up To Hitler: Resistance in Nazi Germany ’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.