The ‘100 Objects’ series from Pen & Sword has become a popular approach to presenting recent history, examining diverse aspects of a central theme that uncover some fascinating but obscure elements of well-known stories. The famous Battle of Britain fighter station is covered in the recently published (2025) RAF Tangmere in 100 Objects. This volume has a slightly lesser impact than some of the others, as it is reproduced in black and white. Many of the ‘objects’ reproduced here are contemporary black and white photographs, so this is not much of a handicap.

For those interested in the wider history of the RAF, not just the Battle of Britain, this is a welcome addition. The story of Tangmere stretches from the First World War, when Tangmere was designated as a Training Depot Station for the United States Army Air Service (USAAS) to the jet age of the 1960s. The following excerpts look at three individuals closely connected to Tangmere:

A Tangmere Military Cross

Flight Lieutenant Courtney Willey MBE, MC

The Military Cross was instituted in 1914 ‘ to recognise the distinguished service in time of war of Officers of certain ranks in our Army’. It is, therefore, unusual for a member of the RAF to be a recipient. Just how unusual is revealed by the research of Michael Maton who notes that of the 10,000 or more MCs awarded in the Second World War, just sixty-nine (including one Bar) were to RAF personnel. The German assault on Tangmere on 16 August 1940, led to one of these awards - that to Flying Officer Dr Courtney Beresford Ingor Willey.

Born into a medical family in Hendon, Middlesex, in 1912, Willey was educated at Balliol College, Oxford. He volunteered for service in the RAF in March 1940 and, having been granted a commission, was posted to RAF Tangmere, to take up the role of medical officer for 601 (County of London) Squadron, a few weeks later in May.

Willey was on duty when the station’s tannoy system announced the impending arrival of the Luftwaffe bombers. One of his first actions was to move ten of his patients from the sick quarters to a nearby air raid shelter. As the bombs rained down, the sick quarters took a direct hit. The citation for Willeys award of the MC reveals a little of his subsequent actions:

‘Flying Officer Willey was buried in the debris of a building which received a direct hit during an intensive air raid on an aerodrome. In spite of slight injuries and shock, this medical officer extricated himself and immediately rendered first aid to other injured personnel. He displayed a fine example of calm behaviour and efficiency.’

It is said that many of Willeys injuries were caused when the buildings chimney breast collapsed on him - interviewed in 20131 he declared that he had been saved by his tin helmet.

That he had narrowly escaped a worse fate was revealed by Air Vice-Marshal Sandy Johnstone, then a squadron leader in command of 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron. I drove over to Tangmere in the evening,’ he wrote, ... Already stories are going around of how the fellows reacted during the aerial onslaught - some patently numbed by the force of it, whilst others seem to have become spurred to greater action by the terrifying enormity of the moment. And the heroes were often those whom one would least expect to stand out among their fellow men. Such a man has been our medical officer, Doc Willey, who apparently was doing great deeds throughout the blitz.’

During the months following the raid Willey served at a number of other Fighter Command stations before being posted, in April 1941, to the Far East. As the Japanese moved to capture Singapore, Willey was evacuated to Sumatra and Java. It was there that he was eventually captured, marking the start of more than three years’ incarceration as a prisoner of war, during which time he was one of the many forced to labour on the infamous Death Railway in Burma and Thailand.

Having survived, on his return to the UK Willey was made a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for his work in the PoW camps. Post-war he was to become a consultant physician at West Cumberland Hospital and lived at Woodend, near Egremont. He passed away in December 2004 aged 90.

Like so many of the items in this book, Willey’s Military Cross is on display at Tangmere Military Aviation Museum.

Stained Glass Window, Boxgrove Church

Commemorating Pilot Officer William Meade Lindsley ‘Billy’ Fiske III

Despite the best efforts of the staff at Chichester, Pilot Officer Fiske did not survive [after crash landing during the raid on 16th August]. As Willey had feared , Fiske succumbed to his wounds the following day. He was 29 years old.

Pilot Officer William Meade Lindsley Fiske III was one of only two Americans who died in the Battle of Britain. Having won gold medals with the US Olympic bobsleigh teams in the 1928 and 1932 Olympics, Fiske was no ordinary American. He was also an exceptional driver and had taken part in the Le Mans 24-hour races.

Having learnt to fly pre-war, he took the decision to risk losing his American citizenship to enlist in the RAF. After completing his flying training, Fiske was posted to 601 (County of London) Squadron, otherwise known as ‘The Millionaires Squadron’.

On the morning of 16 August, twenty-nine Stukas of l/StG2 targeted RAF Tangmere. Already airborne, 601 Squadron was ordered to patrol base at 20,000 feet and soon saw the incoming Ju 87s which they dived on to engage.

It was during this dogfight that Fiske is believed to have been hit by return fire, forcing him, badly burned, to make the emergency landing back at Tangmere.

One member of 601 Squadron who had fond recollections of Fiske was Squadron Leader Hugh ‘Jack’ Riddle: ‘My memories of Billy as a pilot was that he was quite exceptional. His Flight Commander, Sir Archibald Hope, having assessed Billy’s flying ability on arrival with the squadron, said

“In all my flying experience I have never come across a pilot with such completely natural flying ability, and quick reactions. He made his aircraft become part of him.” Archie was definitely impressed!

‘Billy liked to talk with everyone around him, particularly the ground crews. He wanted to know them and all about their jobs, aircraft maintenance and where difficulties lay - always helpful. Very soon he managed to endear himself to the whole squadron - not just the officers, but the other ranks too.

There was club a few miles away from the airfield at Tangmere and this was made our unofficial Squadron Headquarters. It was somewhere pleasant, overlooking the waters of Chichester Harbour, where our wives and friends could meet and be with each other, and wait together until we could be free from Tangmere. Billy always seemed to get there before I did - maybe his motor car was faster than mine - I’m sure it was!

...

Billy was aware and caring, a very nice aspect of his character.’

Fiske was laid to rest a short distance from RAF Tangmere, in the grounds of the Priory Church of St Mary and St Blaise at Boxgrove, on 20 August 1940. His coffin was draped with both the Union Flag and the Stars and Stripes.

The 601 Squadron Old Comrades Association had originally considered commemorating Fiske with a memorial table, but in conjunction with the Priory, who wanted to enhance the aesthetics during a restoration of the Church, the suggestion of a stained-glass window was made and adopted. Designed by Mel Howse, it was unveiled on 17 September 2008.

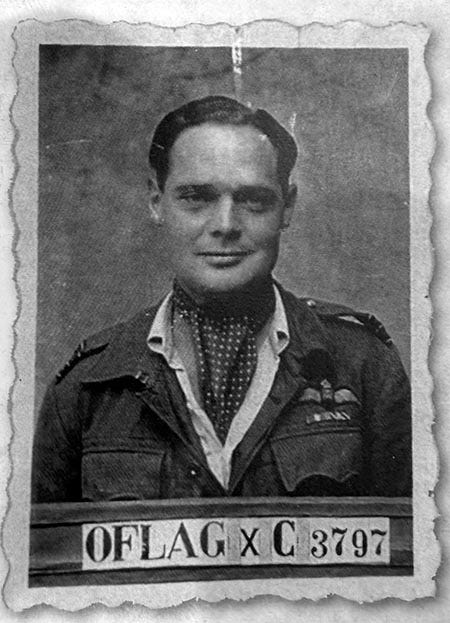

Douglas Bader’s PoW Photograph.

The Tangmere Wing Loses its Famous Leader

An early casualty of the RAF’s increasingly offensive stance in 1941 wasalso one of the most famous pilots to be associated with RAF Tangmere - Douglas Bader.

On 9 August 1941, Bader led the Tangmere Wing which had been tasked with providing an escort for Circus 68, a bombing raid on Gosnay, near St Omer. Sergeant Geoff West was flying in place of Bader’s normal wingman, Sergeant Alan Smith. As two of the Wing’s three squadrons crossed the French coast, they soon became embroiled in combat with numerous Bf 109s. In the ensuing melee Bader was ‘downed’ , though exactly what happened cannot be said with complete certainty; some say he was shot down, others that it was the result of a mid-air collision, with a friendly aircraft or otherwise.

Regardless of the circumstances, the Tangmere Wing’s leader was forced to abandon his Spitfire. Back at Tangmere, the indomitable pilot was duly posted as missing. Then, on 14 August the German authorities notified the British, via the Red Cross, that Bader had in fact survived, albeit that he was now a prisoner of war. Group Captain Woodhall broadcast the welcome news over Tangmere’s tannoy system.

It transpired that in abandoning his aircraft, Bader had lost one of his false legs. The Germans took the unusual step of guaranteeing free passage for an RAF aircraft to deliver a replacement to Oberst Adolf Galland’s JG 26 airfield at Audembert. The British declined the offer, but, instead, dropped a spare leg by parachute from a Blenheim during a Circus operation to Longuenesse on 19 August.

Smith, who had just been commissioned, was one of the pilots who escorted the bombers that day: ‘I can still remember seeing the box dropping under the parachute; it was one hell of a day, low broken cloud and rain. We had six Blenheims, the weather was appalling, and the bombers could not drop their bombs on the target at Lille, but the leg was dropped over St Omer.’

Following his capture, Bader was initially taken to hospital in St Omer. His missing right leg was then found near the Spitfire’s crash site. Repaired, it was returned to him by his captors. Seizing the moment, Bader made his first attempt to escape using a rope made of bed sheets to climb down from a window. His liberty, though, was short lived.

Eventually, incarnated in the infamous Colditz Castle, Oflag IVC, it would be years before Bader would see Tangmere again.

Sir Alan Smith later recalled the effect that Bader’s loss had:

‘Morale was affected; we thought we would get our revenge as they had aken Bader away. A real loss to the Wing. He had such a strong personality and was a good leader. I can’t say that had I been flying that day things would have been different, but I often wonder if I had been there, if I could have made a difference at all. Maybe I would not have come back?’

© Mark Hillier and Martin Mace 2025, ‘RAF Tangmere in 100 Objects’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

Probably 2003 as he died in 2004. The Royal College of Physicians has a brief biography of Willey.