'Dowdings Eagles'

Accounts of Twenty-five Battle of Britain Veterans, telling the story of their flying experiences, including operations before and after the battle

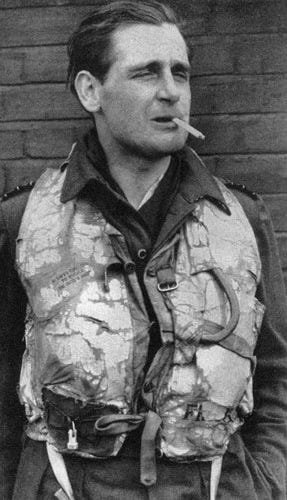

There are many accounts of the Battle of Britain, each with its own approach to the narrative. In 2015, Norman Franks, an experienced aviation historian, sought out some of the last remaining survivors; in long first-person accounts, he tells the story of RAF fighter pilots throughout a long war. Everyone fighting in 1940 had to contend with some rudimentary, even experimental, technology. By the end of the war, it had been completely transformed, and a new aviation era was dawning. It was more due to luck than judgement that many of Dowding’s Eagles were lucky to survive those early days, much less the whole war.

This is part of the story of Myles Duke-Woolley DFC, describing his experiences flying a Blenheim night fighter in the days before radar:

When the war started all the lights went out so we’d be flying over a totally blacked out countryside, except when there was some sort of moon. All we had on the airfield then were the shaded glim-lamps, which couldn’t be seen until you were down to about 2,000 feet and pretty close (hopefully) to the airfield. That was why so many pilots were killed in the early part of the war. Fortunately, some of us had started thinking about these problems before the war began. My flight commander, “Spike” O’Brian [Flight Lieutenant J S O’Brien. Later Squadron Leader, DFC, killed in action leading 234 Squadron on 7 September 1940.] and I talked this over and had started to plan what we should do and how we might do it. We imagined we were somewhere over the Wash in a jet black sky and worked out course and distances to get us back to base.

‘We hadn’t, of course, the slightest idea how we were going to find a target. It wasn’t until well into 1940 that Spike said to me that we had some electronics expert and new instrumentation to see and he volunteered me to fly it around. It was fitted into a Blenheim and it so happened that the “expert” had been at Marlborough with me, and had been working on the first A.I. gear [Airborne Interception radar]. It was very heavy and I recall that no air gunner wanted to come with us!

‘We took off and climbed to 6-7,000 feet and he got ready to switch the “gubbins” on. He said, OK, and switched it on. There was the biggest blue flash I’d ever seen which seemed to zip past me and shoot out in front. I said, “Wow! If there had been an aircraft in front of us we’d have burned him up!” He said he was awfully sorry but the thing had blown up! The insulation had broken down completely, but it was a spectacular flash – just like a ray gun.

‘He reappeared about a month later with the Mark 2 version and we flew this about quite a lot, and we did in fact make an interception one night. It was very difficult as each time I turned, the enemy aircraft turned the other way and we lost it. Then we picked up another one and he said it was flying away from us, so I increased speed but still it was going away from us. Eventually I had to throttle back. Then it transpired that this early A.I. worked just as well backwards as forwards, so in fact, what we’d been doing, was not chasing a German, but running away from one. So the A.I. disappeared for the second time whilst they got it to work just forwards.’

Eventually Duke-Woolley shot down a night raider. This came on the night of 18/19 June 1940, six miles north-east of King’s Lynn, by which time he had become a flight commander. Just thirty seconds earlier on this same night, Flight Lieutenant A G ‘Sailor’ Malan DFC of 74 Squadron had shot down a Heinkel 111 flying a Spitfire, so Myles’ kill was the second night victory for the RAF, although he was in a Blenheim 1f.

In fact British defences claimed four raiders down this night, the luckless German unit being KG4 operating from Merville, France. Malan shot down the bomber piloted by Leutnant Erich Simon, the sole survivor of his four- man crew, and he himself had baled out wounded, as his aircraft crashed in Chelmsford, Essex. Myles’ victim crashed at Cley-next-the-Sea, Norfolk. The pilot had to ditch just off shore and the crew swam ashore. Among Oberleutnant Ulrich Jordan’s crew was the Gruppenkommandeur, Major Dietrich Fr. Von Massenbach. RAF fighters downed three more He111s this night – a rare success for Fighter Command.

… we’d never had any real briefing on how to actually shoot down an aircraft.

Myles recalled the night for me:

‘ I have never been so frightened before in my life and was never so frightened again. I was on patrol off the East Coast, over the Wash, on a gin-clear night, and Control called up to say that some German aircraft had been raiding the Midlands and some of them were coming our way. I looked to the west and could see a number of searchlights criss-crossing about, and called back to say that it looked as if the searchlights had somebody and should I investigate? They said no, it’s being dealt with so I just watched. ‘Then, about 10-12 miles away I saw a very small yellowy light going down, then it went out, then I thought I saw a parachute, and realised that one of our aircraft had intercepted it and it had been shot down.

The yellowy thing had indeed been a Blenheim on fire. I called Control again and said I was going to engage. After a short silence I was told to engage in my own time. I then realised we’d never had any real briefing on how to actually shoot down an aircraft. The only instruction we had had was by some chap who’d shot something down in 1918, and that the thing to do was to rush up behind the bomber, close to 100 yards and with our outstanding armament, blow it apart!

‘So as I closed in I began to realise I should also soon be fired at myself, that I had no armour protection in front of me, my fuel tanks were not self-sealing, and the more I thought about it, the more I realised that I was going to live just long enough to get tangled with this German aircraft – in about four minutes. I had been married just over nine months (31 August 1939), and my wife had just given birth to our first child and I knew I was never going to see it. I was convinced of it, I just could not see any hope.

‘I was thinking furiously on how I might attack and get away with it and then a plan occurred to me, which I then imparted to my gunner. Fear was growing inside me and it came up to my throat and I realised I wasn’t able to talk. Then, an extraordinary thing, I began to hear my voice speak and it was absolutely calm. I told Control I was in touch with the bandit and would engage it shortly.

Then, this same calm voice spoke to my gunner: “Have you got your parachute on?” He said no, so this voice then said: “They’ve still got a searchlight on him, and what we are going to do is this. I’m going to keep to port until the light goes out, then I’m going to come up in line astern of him at 100 yards, and open fire with a 5-second burst. If that doesn’t work I’ll come up under his wing and I shall want you to put bursts up into him. If that doesn’t work, we’ll have to go back and start again.” So that’s what we did.

I let my gunner have a go but we still didn’t appear to be doing any damage.

‘I flew alongside the bomber, about 500 yards away, until the last light flicked out, came up behind it, put the sight on it and counted out five seconds as I pressed the gun button. I then broke off and looking where I’d just been could see all these red flashes, which I later realised was return fire from the German gunners. I then went in again but after another long burst the bomber was still flying along. I then flew underneath it and let my gunner have a go but we still didn’t appear to be doing any damage.

All the time something kept nagging in my brain that I was doing something wrong. Then I suddenly realised that our guns were harmonised at 250 yards. This meant that at 100 yards, the range I’d been told to fire from, I was hardly hitting him at all, so I deduced I had to fly at least four feet higher for it to be more or less right. ‘I slid in again, aimed high up on the German’s tail-fin, fired and broke to port, but this time the return fire was less. I then pulled in again, fired once more with a 7-second burst and as we broke, we were hit. There was a smell of cordite, and a scream from my gunner. As I turned, the bomber disappeared. My gunner said he’d been hit.’

In the event, the air gunner had not been hit. A couple of bullets had come up under him and hit his chest-type parachute, which had knocked it upwards and it had hit his chin. Myles then asked the gunner if he could see the German, and he replied, “Oh, yes, he’s on fire.”

Coming back over the coast, Myles’ starboard engine stopped. A bullet had hit one tank, and fuel had drained out. However, he got home and landed safely.

© Norman Franks 2015, ‘Dowdings Eagles. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.