Enduring the Unendurable: Japan in the First Weeks After Defeat

A guest post looking the experiences of the Japanese as they came to terms with the end of the war - and American plans for their future

As we bid farewell to 1945 (for another five years) I am very pleased to be able to conclude with a piece by fellow Substack author and podcaster Christopher Harding. This picks up where my last post from 1945 - The end of the war in the Pacific - ended.

Harding published the bestselling The Japanese: A History in Twenty Lives in 2023, just one of his insightful and revelatory books about the people of Japan. Here he examines the many conflicting influences on the Japanese people as they struggled to survive the end of the war and build a new future - ‘a daily encounter with dislocation, hunger, shame, and the frightening unknown’.

Enduring the Unendurable: Japan in the First Weeks After Defeat

At noon on 15 August 1945, millions of Japanese gathered around crackling radios to hear a voice few had ever heard before. It was the Emperor’s. In archaic Japanese, which few of his listeners could fully understand, he told his people they must ‘endure the unendurable, suffer the insufferable.’ The war was over.

And yet, in the days and weeks that followed, ‘over’ was hardly the right word. For ordinary Japanese, defeat was not a single moment but a daily encounter with dislocation, hunger, shame, and the frightening unknown.

The surrender itself was nearly sabotaged. A group of young officers tried to storm the Imperial Palace to steal or destroy the recording of the Emperor’s broadcast, so desperate were they to prevent capitulation. The record had to be smuggled out in a laundry basket.

Even after the broadcast, rumours spread of last-ditch attacks being planned against the approaching American fleet. Remaining Japanese aircraft had to be disarmed, their fuel tanks emptied, lest rogue pilots take off on final kamikaze missions. Senior officers of the Imperial Japanese Army, including Arisue Seizō, stockpiled weapons and hundreds of millions of yen in cash, preparing for a guerilla movement against the incoming Allied forces.

Like most of those postwar kamikaze missions, resistance plans never got off the ground. Army stores, set aside for a prolonged battle to defend the homeland, were quickly looted and the proceeds – carried away in convoys of trucks – fed onto the black market: the foundation of many a postwar fortune for Japanese gangsters.

Meanwhile, millions of ordinary people poured daily out of Tokyo on overloaded trains, clinging to rooftops and hanging off the sides, heading into the countryside for search for food. Most of Japan’s cities had been devastated by American napalm and few Japanese yet knew quite what had transpired at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Rationing had broken down and people did what they could to eat. While some tried trains, others smuggled: young women wrapping up sacks of rice to look like babies, strapping them to their backs and cooing at them whenever they had to walk past a police officer.

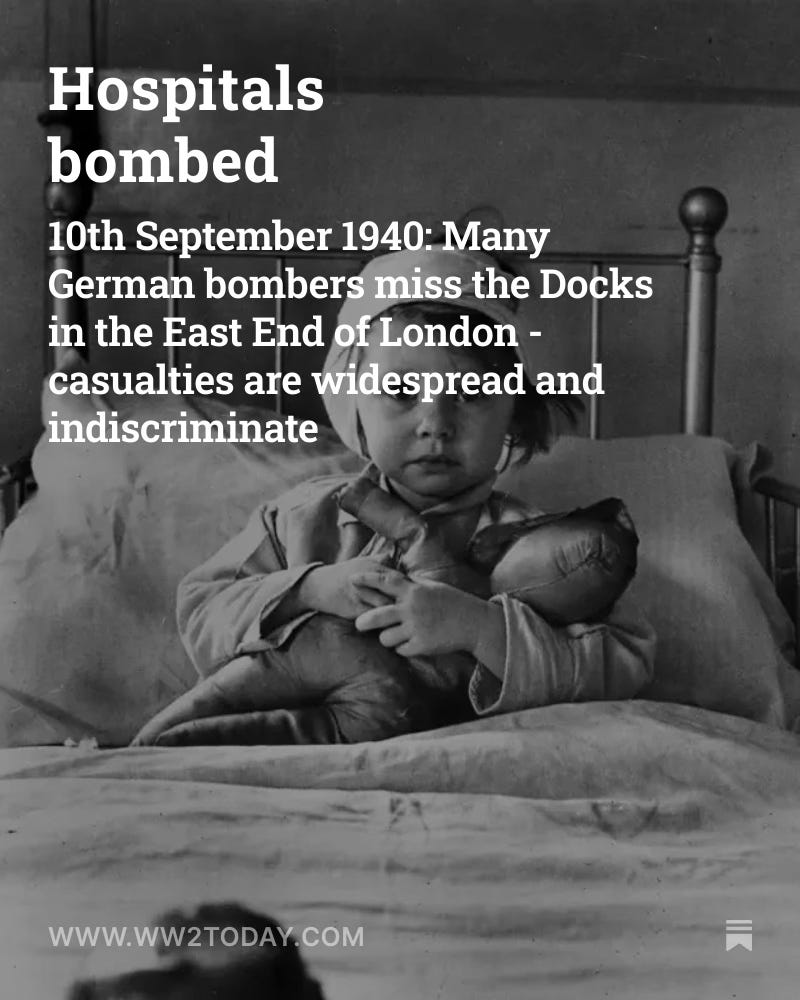

As August turned into September, eighty years ago, a mood of bewilderment deepened into disgust. Two million soldiers and nearly 700,000 civilians were dead; nine million were homeless. Malnourishment and disease spread, but so too did news of atrocities committed by Japanese forces abroad, the first of whom began arriving home in the autumn.

Anger turned inward: at soldiers and at Japan’s militarists, who had first lied about the need for war and then failed to defend civilians against its consequences. American bombers had met little resistance from fighters or anti-aircraft guns when they flew low over Japan’s cities in the spring and summer of 1945. All the most valuable equipment and most precious personnel had been thrown into the fight abroad.

Alongside anger ran fear. People in Japan had been told to expect that should Allied soldiers make it to the Japanese home islands, the consequences would be grim – not least for Japan’s women and girls. This was largely propaganda, but there was an element of real concern. In the weeks after surrender, the Japanese authorities set up a ‘Recreation and Amusement Association’, recruiting women with few other options to provide sexual services to incoming foreign troops. This was better, so the reasoning went, than subjecting more respectable Japanese women to violence.

‘We go forward with culture.’

Amidst all this, there was still room for a fragile sense of optimism. One of the standout moments from that otherwise grim autumn was the release of a film called Soyokaze (‘Soft Breeze’). A wartime project resurrected immediately after surrender and produced in an extraordinary seven or eight weeks, the film was a classic of cinema in almost no one’s estimation. Its main song, Ringo no Uta (‘Apple Song’), was insultingly basic: ‘the apple’s lovable, lovable’s the apple.’ And yet there was something about the glowing young actress who starred in it, Namiki Michiko, skipping through an orchard and singing about the simple goodness of blue skies and luscious fruit, which resonated with an exhausted population. There was a sense that at some point the sun might really break through the clouds.

Alongside film ran music. Jazz had been big in Japan before the war, but people had been forced to hand in their records or else hide them somewhere at home when the authorities decided that anything that smelled of European or American culture was to be banned. Now, incoming American soldiers brought with them the latest in jazz and other musical styles. Some of them were musicians themselves, including the pianist Hampton Hawes. Others were enthusiasts, who helped to drive a demand for Japanese musicians to play at live venues across the country.

Japan’s Education Minister put it well in September 1945, all but offering a manifesto for the country in the second half of the twentieth century: ‘We go forward with culture.’

Into all this came the Americans, led by General Douglas MacArthur and intent on achieving three core aims. First, Japan was to be demilitarized. The army disbanded, the empire dismantled and war forever to be renounced as a way of serving Japan's interests abroad. Second, decentralization. The Americans believed that big conglomerates, known as zaibatsu, were partly responsible for militarism in Japan, such were their close relationships with senior figures in the government and the armed forces. These conglomerates, like Mitsubishi, were to be broken up. Thirdly, democratization. MacArthur and his young team had a deep faith in the idea that democracy is the best means for human beings to flourish. They believed that if the Japanese were given a true, functioning democracy, their creative energies would be released to rebuild the country.

Quite how all this would go, no one could say in early September 1945. At this point in time there was still the chance that either an armed resistance movement against the Occupation or the anger of ordinary civilians would derail plans for occupying and reforming Japan – which had begun to be laid not long after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Emperor had simply asked the people of Japan to ‘endure.’ And endure they mostly did, waiting to see what this latest turn in their country’s long and tumultuous history would bring.

© Christopher Harding 2025, cultural historian & broadcaster based at the University of Edinburgh. Christopher Harding is on Substack as well as being the author of several books, including the bestselling The Japanese: A History in Twenty Lives.