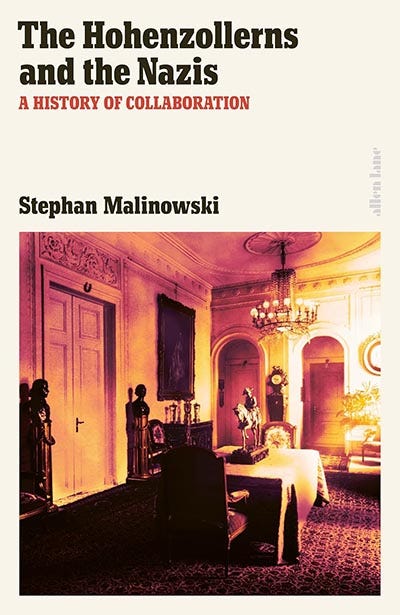

'The Hohenzollerns and the Nazis'

How the German Royal Family collaborated with the Nazis throughout the 1930s and into the war years

Legions of historians have pored over German history in the years following the First World War, seeking to understand every aspect of the rise of the Nazis. A new study, just published in 2025, reveals that there are still aspects to uncover. 'The Hohenzollerns and the Nazis: A History of Collaboration’ traces the history of the Royal Family and the German aristocracy as it manoeuvred for relevance and a chance to regain power after the First War.

Kaiser Wilhelm had been exiled to the Netherlands in 1918 and forced to renounce his throne. Yet his family remained intimately connected to the German aristocracy and the German military. They were as adept as any Royal Family in the modern age at managing their public image. In private, they were at best ambivalent about the Nazi’s anti-semitic policies. They were valuable to the Nazis in giving them legitimacy. Yet, as Hitler consolidated his grip on power, there was no room for any rival power base.

The following excerpt looks at events in 1940 and reflects that popular support for the Royal Family was not a sign that they opposed the Nazis:

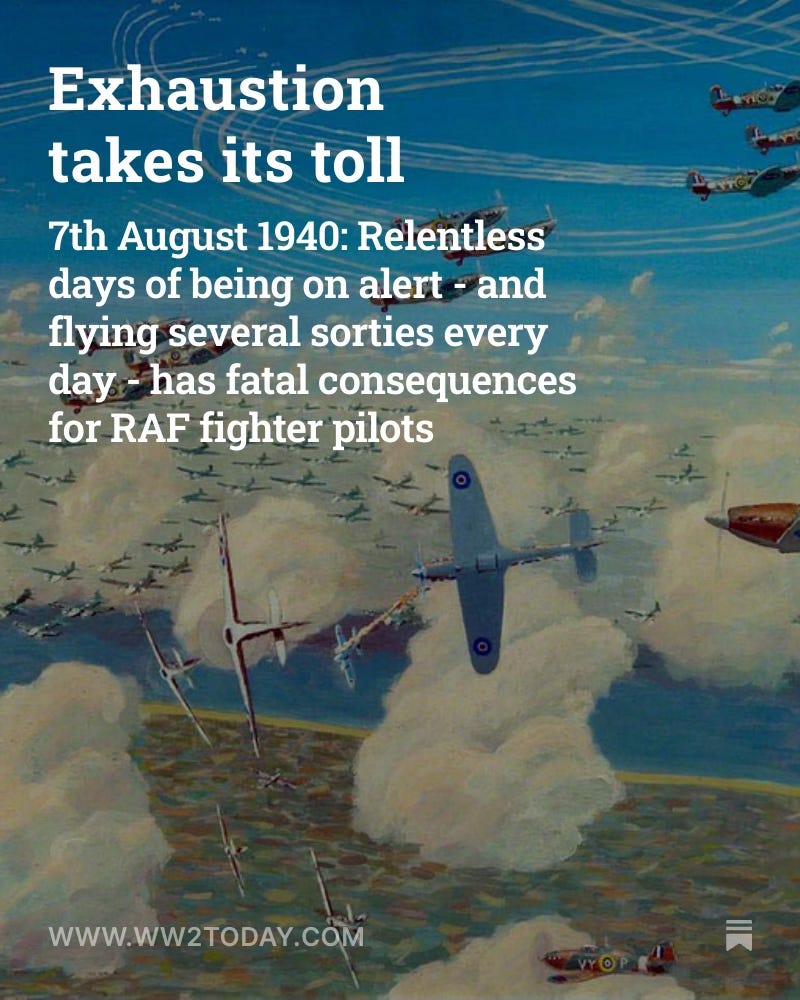

Many historians have tried to associate the Hohenzollerns with the thinking of traditional German conservatives, including the military circles that actively resisted Hitler. But when Germany provoked the Second World War in September 1939, the male members of the royal family offered no opposition at all to that act of aggression. Instead, they were content to occupy lower positions of leadership in the Wehrmacht and were among those who most loudly applauded the Nazi’s early military triumphs.

All the way back in October 1934, the crown prince’s son Hubertus had joined the military, and when Germany launched its aerial attack on Poland, Louis Ferdinand was a member of the Luftwaffe. This was noted in the international press. The New York Times listed eight actively fighting Hohenzollern princes in September 1939, but the list was incomplete. In fact, 'all able-bodied Hohenzollern princes’ had been drafted, and at the onset of hostilities thirteen family members were 'directly serving at the front’ . One newspaper report, in which Prince Oskar declared his family’s loyalty to the regime after Georg Elser’s attempted assassination of Hitler, named twenty-two Hohenzollerns at the front.

Six weeks after the attack on Poland, the crown prince’s eldest son, Wilhelm, reported that things were calm at the front with 'plenty of milk, eggs, butter and poultry’ . The campaign had been 'instructive’ , he added, writing to an old friend with considerable experience of battle:

‘Here in Poland, there is fighting again, but of a completely different sort than we learned.’

Considering the extreme brutality of Germany’s war in Poland, it would have been interesting to learn more about the differences contained in this missive.

A bit earlier on, Prince Wilhelm revealed:

‘We are already mentally preparing ourselves for the west, where fundamentally different methods of fighting will have to be used.’

Ironically, Wilhelm - the most military-minded of all the crown prince's sons - wouldn’t survive the first two weeks of fighting in the west. On 23 May 1940, three days before Germany opened its major offensive, the 33-year-old was badly wounded in the Battle of Valenciennes just behind the Belgian border. The heroization of the prince that commenced immediately after his death included vivid, stylized descriptions of his end, evoking the fighting spirit, leadership, selflessness and sacrifice that were allegedly typical of Prussian military clans.

‘Tempestuously’ First Lieutenant Wilhelm, the radiant idol of his company, led the charge, taking bullets to the lungs and stomach. But while lying wounded in the line of fire he maintained an overview and continued to give commands to his men, rescuing German victory and saving the lives of many comrades, before succumbing to his injuries the following day in a field hospital.

Wilhelm’s cousin Oskar, the son of the crown prince’s brother of the same name, had already fallen while leading a company in Poland in mid-September 1939. But it was the death of Prince Wilhelm that would open a further gap between the Hohenzollerns and the Nazi regime.

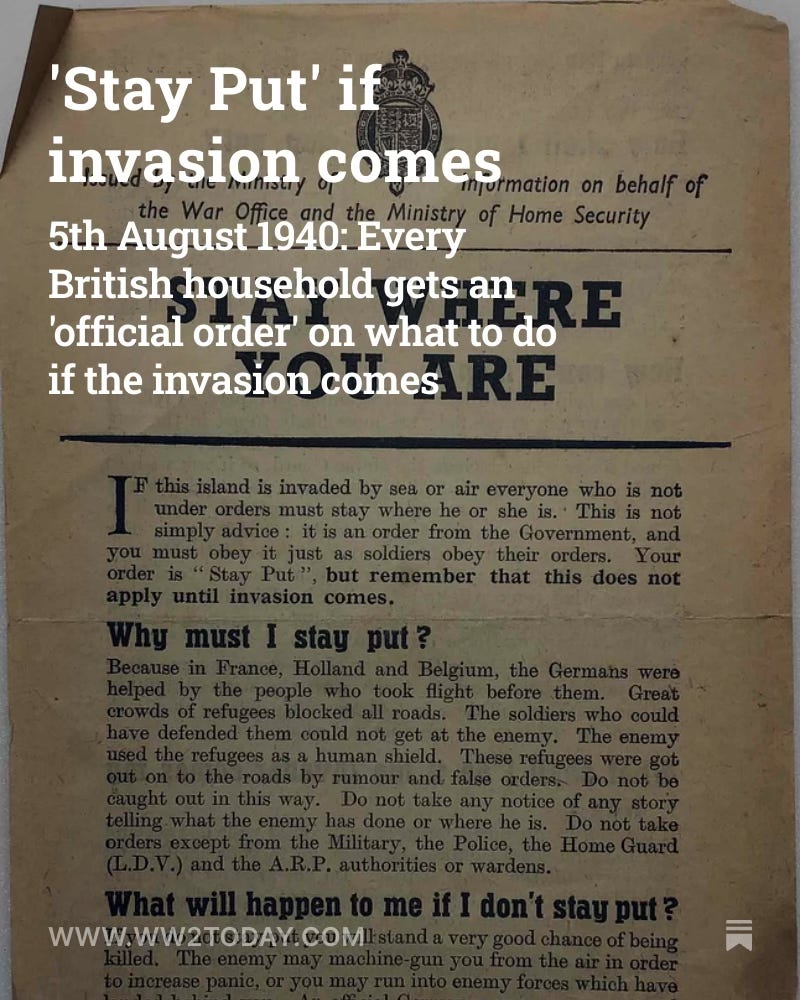

The military funeral for the popular prince, who had caused a nationwide stir in 1926 merely by appearing at Reichswehr manoeuvres, turned into the sort of event that didn’t sit well with the Nazi regime, and it continues to this day to be interpreted as evidence of the royal family's opposition to Hitler.

On 29 May 1940, some 50,000 people turned out to form a guard of honour between Potsdam's Church of Peace and the Antique Temple in Sanssouci Park. As had also been the case with the 1921 funeral of the former empress Augusta Victoria, the massive turnout could hardly be interpreted as anything other than a public display of connection with the royal family. But the funeral-goers didn’t necessarily see monarchy as a preferred alternative to the existing regime. Their engagement was prompted by a charismatic officer who had fought on the frontlines against Poland and France and whose 'hero’s death’ came about as part of Germany’s successful conquest of Europe: France had been defeated, and the British military expedition was surrounded near Dunkirk. The masses who turned out in Potsdam most likely also wanted to mourn the first 50,000 young Germans who had lost their lives in the Wehrmacht.

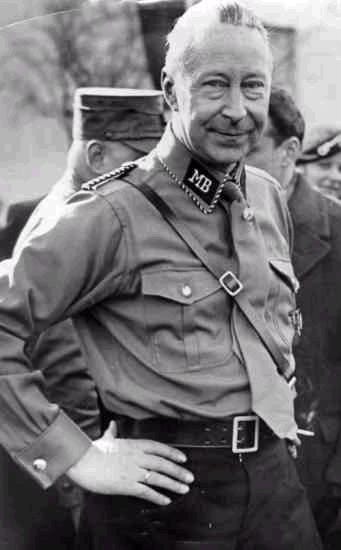

Thus, there was just as little reason to interpret the event as a symbolic stand taken by conservativism against the Nazi regime as there had been with the Day of Potsdam seven years previously. Even the appearance of military grandees such as the omnipresent Mackensen, wearing their old medals and imperial hussars' uniforms with fur caps and short tiger-skin coats, needs to be seen for what it was.

In 1935, Mackensen himself had accepted as an endowment from Hitler his 1,250-hectare Brussow estate and, a bit later, a one-off payment of 350,000 Reichmarks. By 1940, one of his sons was a decorated Wehrmacht lieutenant general, and another would become an SS Gruppenführer.

‘As long as God grants me life, I will remain loyal and grateful to Adolf Hitler, the leader and rescuer of my German fatherland,’

the 93-year-old field marshal would proclaim in late 1942.

‘He is the German man I have looked for in my fatherland since 1919.’

Nonetheless, the Nazi leadership felt that a potential rival power had shown its face in Potsdam. Hitler’s reflexive aversion to anyone who might in any sense be considered a successor and the great energy he invested in suppressing any forms of emotional or political affinity beyond the regime's control made further distance between the monarchy and the dictatorship inevitable.

The Nazi regime had long desired clearer borders between the military leadership and the Hohenzollerns. For this reason, the Crown Prince's son had been denied a post as an active Wehrmacht officer, and Crown Prince Wilhelm’s brother Oskar, who had been a regimental commander at the start of the war, was nominally promoted to major general and transferred to the reserves.

Following the funeral for Prince Wilhelm, the regime issued the 'prince decree’ , which prohibited members of the former ruling family from being deployed in battle. The decree was enhanced in May 1943 when all members of the former 'ruling houses’ were technically excluded from the Wehrmacht, although a few exceptions to the rule were allowed.

©Ullstein Buchverlage 2021, © Translation Jefferson Chase 2025, 'The Hohenzollerns and the Nazis: A History of Collaboration'. Reproduced courtesy of Penguin Random House UK.