'Soviet Infantryman on the Eastern Front'

Another highly illustrated study of the ordinary soldier at war

A complement to last week’s excerpt about the German Infantryman is Simon Forty’s The Soviet Infantryman on the Eastern Front.

The scale of the suffering of the people of the Soviet Republics - not just the Russians - during the war is hard to comprehend. Many ethnic groups had already suffered under Stalin’s paranoic rule - now they were to face unspeakable crimes at the hands of Hitler. The barbarism and hatred towards them turned them into a formidable enemy. The Red Army infantry proved capable of enduring extraordinary hardships, brutal discipline and often incompetent leadership in battle - yet emerged victorious.

The following excerpt looks at some of their motivations:

How Did the Soviets Turn It Round?

The Soviet defense stiffened at the end of 1942. Bravery, throwing millions of troops—often with insufficient training or weapons—into battle, assistance from the West, and the ability of the state to impose a total war footing that saw everyone heavily involved from the start: all these things contributed as did the phlegmatic character of the Soviet soldiers who were prepared to accept the many inherent privations.

However, alone, these factors may not have been enough to turn the tide. Many of the territories the Germans conquered could have been turned against the Soviets - the recently annexed Baltic states had historically always fought against Russia. In general there were strong anti-communist feelings throughout the Soviet Union, particularly among those who had been affected by dekulakization—the redistribution of farmland that saw nearly two million peasant farmers deported in 1930–31—and collectivization, the move to state control of farms that had led to famines killing at least 10 million. As many as half of these deaths were in Ukraine, recently ravaged by the Holodomor famine that may have been part of the repression of Ukrainian independence or a result of the policies of industrialization and collectivization promoted by the Soviet state. Either way, the 1932–33 famine killed conservatively between three and a half and five million Ukrainians.

However, there was a big “but” - the genocidal views of Hitler and the Nazis that permeated every level of the German army, ensured that only a small percentage of the population under their control accepted their rule. This isn’t to say that there weren’t collaborators- some of whom were motivated by politics, such as the Vlasov’s Russian Liberation Army, or those who joined the Ostlegionen - but many were coerced into collaborating, or chose to collaborate out of an instinct for self preservation by becoming Hilfswillige or Hiwis, “voluntary” auxiliaries. The number of Hiwis reached 600,000 by 1944. Many were captured Red Army soldiers who otherwise faced death as POWs.

Hitler, his generals, and many of his armed forces had a straightforward attitude towards the attack on the Soviet Union, as comments in Generaloberst Franz Halder’s diary show. He identifies the German reasons for war as discussed in the Führer’s office: the clash of the two ideologies.

[Hitler gave] a crushing denunciation of Bolshevism, identified with a social criminality. Communism is an enormous danger for our future. We must forget the concept of comradeship between soldiers. A Communist is no comrade before nor after the battle. This is a war of extermination. If we do not grasp this, we shall still beat the enemy, but 30 years later we shall again have to fight the Communist foe. We do not wage war to preserve the enemy. ...

Extermination of the Bolshevist commissars and of the communist intelligentsia. The new states must be socialist, but without intellectual classes of their own. Creation of a new intellectual class must be prevented. A primitive socialist intelligentsia is all that is needed. We must fight against the poison of disintegration. This is no job for military courts. The individual troop commanders must know the issues at stake. They must be leaders in this fight. The troops must fight back with the methods with which they are attacked. Commissars and GPU men are criminal and must be dealt with as such. This need not mean that the troops should get out of hand. Rather, the commander must give orders which express the common feelings of his men.

This war will be very different from the war in the West. Harshness today means lenience in the future. ... Commanders must make the sacrifice of overcoming their personal scruples.

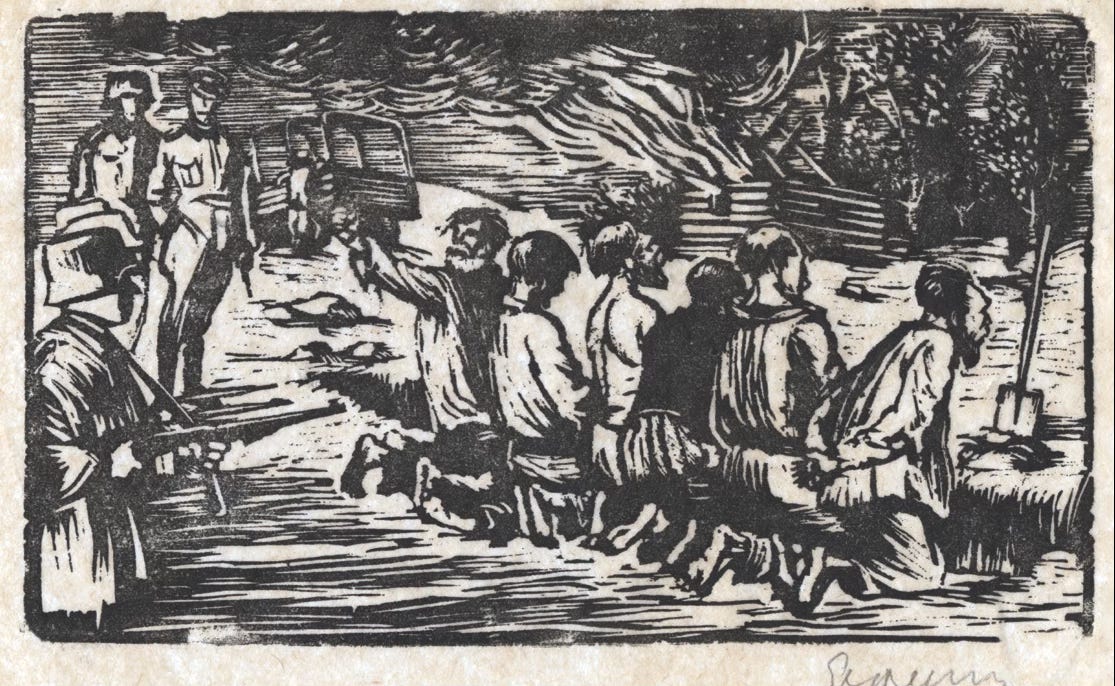

It is quite obvious what Hitler expected of his men: ruthless extermination. This was to be a war of annihilation with the exploitation of the resources - including slave labor - and, ultimately, the resettlement of the lands conquered by Germans. Civilians, POWs, and, of course, Jews were killed in their millions. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that 17 million people were murdered by the Nazi regime and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945. Of these, over 10 million were Soviet, including at least 5.7 million non-Jewish civilians and 3 million POWs. The German Army was complicit in these murders from the start - right down to the infantrymen who either did the killing or handed prisoners to the SS-Einsatzgruppen behind the front lines.

These mass murders - unsurprisingly - did have a negative effect effect, convincing the Soviet population to support the Bolsheviks although many were distinctly unfavorable toward the Communist regime. “What was Stalin unable to achieve in twenty years [that] Hitler achieved within one year? That we started to like Soviet rule,” ran a joke in the Ukraine. Gerts Rogovoy expressed his feelings:

I did not mention the hatred I felt toward the Germans. There is a town there called Kalach. Near Kalach we saw what had been a camp for Soviet POWs. The dead lay frozen in dugouts. Nearby stood stacks of railroad ties that they had placed there. Ties, corpses on top, then ties again ... some were burning, some were not. I had this urge, this sense of hatred toward the Germans ... In the sixties as a coin collector, I made contact with some Germans ... Only in the sixties did I begin to see them as people. Before that the very sound of the German language would make my insides churn, especially after I found out about Babiy Yar in which I lost my aunt and my cousin and the aunt’s grandson. (BA)

The war in the east was brutal: “You want justice? You want fair play and decency? When you burn thousands of villages and bury children and old people alive in mass graves - then you don’t think of justice, do you?” - a captured German officer was told by a partisan, after the former protested his rough handling.

Another result of the treatment of Soviet civilians by the Germans was the reciprocal treatment meted out by the Soviets as they advanced into German territory, raping and pillaging as they went. “Rage was a powerful incentive to kill - both on the field of battle and between engagements,” Ilya Kobylyanskiy stated, explaining his hatred of the Germans. “As I fought on, I tried to take revenge on them for all of their monstrous offenses.”

Having been under the cosh from the invasion and having suffered larger defeats than those that caused Western powers to surrender in 1940, the Soviet forces around Moscow were at the last moment helped by the extreme weather conditions at the end of 1941 and the arrival of reserves, many from the far east. With the enemy at the capital’s gates, the Soviet counterattack halted the Germans in their tracks and allowed a regrouping. German logistical problems - partly a result of overconfidence and the arrogant belief that they would roll over the Soviet forces before the onset of winter - helped the defenders and dealt the German attack a mortal blow. The German successes in 1942 into the Caucasus masked their strategic failure in 1941, but the writing was on the wall. 1942 saw the Soviets grow stronger as the Germans followed Hitler’s urgings to secure the oilfields in the Caucasus rather than push towards Moscow. The key battles on the Eastern Front took place at Stalingrad at the end of 1942 and then at Kursk in 1943 as Hitler’s final Blitzkrieg campaign foundered against the minefields and prepared defenses of the Red Army. The Soviet infantryman played a crucial role in both battles and although losses were high, morale soared as the invaders were thrown back. Kurt Rogovoy was in Stalingrad:

The time spent at Stalingrad was the most difficult in my life. ... There was a huge number of casualties: both ours and the Germans. Frozen. Despite the freeze, the smell was terrible. ... One time 45 of us were organized around three medium machine guns. ... I was in the vicinity of the Stalingrad Tractor Factory. There was a semi-destroyed building; we were told to take up positions there and not to retreat. The Germans were attempting to break out of encirclement in that area. We hung on for seven or ten days, I do not remember for sure.

Only one of our three machine guns remained operational after that. The water coolers were damaged by mortar fire and the guns could no longer operate. We ran out of ammunition, then we ran out of food. The only thing we had left to do was die. When we ran out of ammunition for our last machine gun, we noticed an escape route. A shell had fallen nearby and blown an entrance into a basement. We climbed through the opening into the basement, and then another shell hit the same spot. We were covered in rubble. We were buried alive, and only had enough room to breathe. It was frightening: to be buried alive. How long was I there ... maybe a day, maybe three, I am not certain. They say that a shell never hits the same place twice, but nevertheless, another shell hit the same place and made an opening. However, I was wounded; a piece of shrapnel hit me just under my left shoulder blade. (BA)

Defeated at Stalingrad, Hitler went back on the offensive at Kursk and launched his panzer divisions at the defenses the Red Army had prepared in depth. Mark Yankelevich was a gun layer for a 45mm antitank gun:

We called [the guns] “Goodbye, Motherland”; they were placed in front of the infantry. I took part in battles on the Kursk–Orel Bulge, [operating] along dangerous tank paths ... where for the first time the Germans began to use heavy Tiger tanks and Ferdinands. I was lucky. I knocked out a tank and was awarded the medal “For Courage.” ... We received instructions: only shoot at the mechanism that moves the caterpillar tracks. You needed to hit the mechanism that turned the caterpillar tracks. It so happened that at one point, four of us were still alive with two guns; we were carrying the shells ourselves. Armor-piercing shells did not work as the armor was very thick. ... When I was in Kharkov, there were rumors of what was happening in Babi Yar. Anger made me act the way I acted. (BA)

Arkadiy Dayel was also on the 45mm guns. His graphic description of the action gives a taste of the dangers of being an antitank gunner in an infantry division:

The tank approaching my trench was maybe 50 meters away, maybe less, coming toward me. I looked around and thought, well that’s it, I am about to be crushed. One of my comrades was wounded in the arm; he was lying there all covered in blood. There were just two of us left. Who was manning the antitank gun? No one was there anymore, only the gun survived. I managed to grab it, and with two or three bullets we managed to take out that tank. Then we followed up with our machine gun. I received my first award for that battle, the Order of the Red Star. That was my most difficult battle.

I and one of my fellow machine gunners survived. There had been three of us. One was hurt badly. He was lying right beside us. I don’t even remember where or how he was wounded. He was taken away later. And there were two dead soldiers lying behind this long gun that I told you about, the antitank gun. My comrade and I, we grabbed this antitank gun together, and with two or three shots hit the tank. And later ... It was hard to be fully aware of what we were doing, how ... We tried to both shoot down the tank and stay alive. Then we fired the machine gun to finish them off. How many did we kill? No one fighting in the war could count who killed whom. Only a sniper could count that. They used to write: so-and-so killed two hundred Germans, another killed this many Germans ... It’s possible ... I didn’t keep track. (BA)

The Germans were held at Kursk and the story of the next two years was one of retreat for the Ostheer and increasing confidence for the Red Army in general and the Soviet infantryman in particular.

© Simon Forty 202, The Soviet Infantryman on the Eastern Front. Reproduced courtesy of Casemate Publishers.