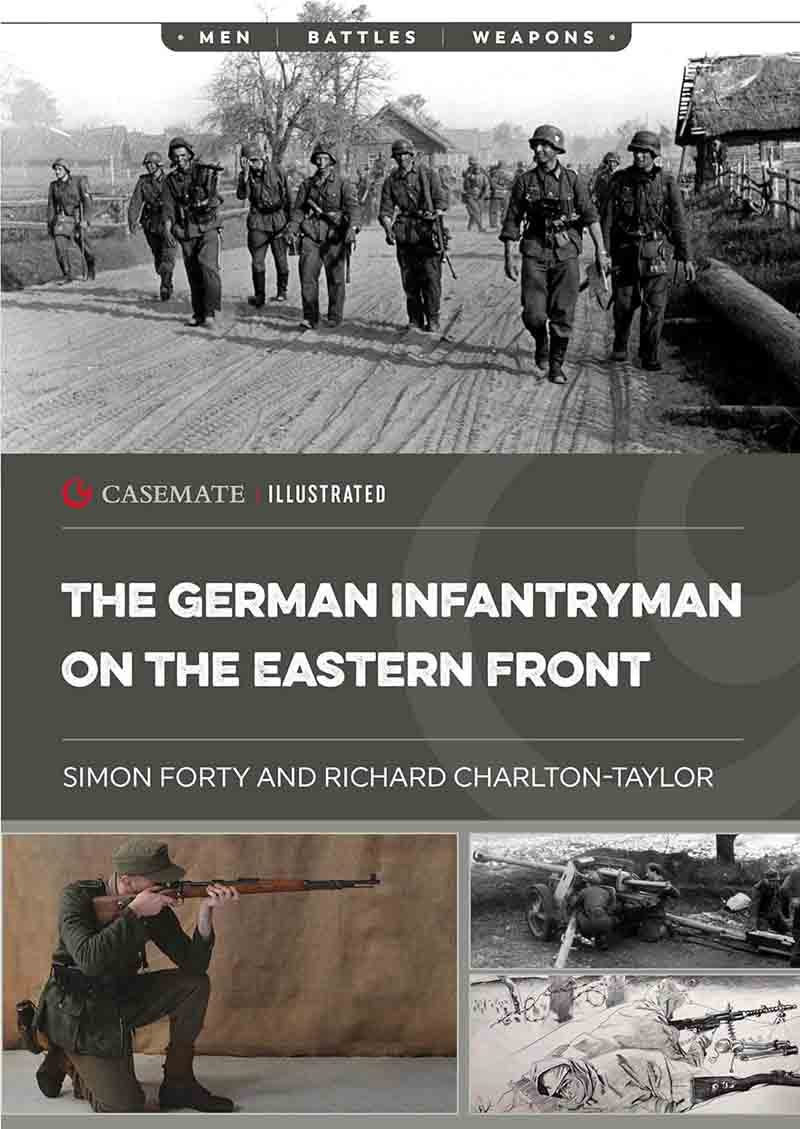

'The German Infantryman on the Eastern Front'

A richly illustrated study of the life of the ordinary soldier

Recently published in the Casemate Illustrated series is The German Infantryman on the Eastern Front. The books in this series draw from a wide variety of sources to tell their stories, with a huge variety of contemporary images.

This volume paints a full picture of the life of the ordinary German soldier in the East, mainly Russia. This was where the most significant part of the war was fought - and where the Landser fought, suffered and died. Over three million men took part in Operation Barbarossa invasion in 1941. The early optimism lasted only months. Soon, they were plunged into a nightmare war of vast distances and an inhospitable climate against an implacable foe. By 1945, nearly four million German troops had died here - 80% of their losses.

The following excerpt looks at the German military organisation that nevertheless maintained its discipline and integrity for those years:

The Soldier

The German soldiers who crossed into the Soviet Union in June 1941 could never have anticipated what they were letting themselves in for. They expected to be victorious. In two and a half remarkable years they had defeated every foe they had come up against, and this gave them huge belief in their weapons, their leaders and their training. They had been indoctrinated to believe in Nazism and their Führer and would do everything asked of them to defeat the enemy and eradicate the world of Jews, Bolsheviks and any Untermenschen (subhumans) who stood in the way of their Aryan destiny.

The Germans of 1939 lived in a militarized society whose young men under the Nazis had been schooled with war in mind. Toughened up by stints in the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth)—which had eight million members in 1939—and the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD— Reich Labor Service), they were then carefully trained for war during their period of conscripted service. Hitler reintroduced this in 1935 when the period of active service was fixed at one year. This was extended to two years in August 1936 for all men aged 18–45.

When German youths were inducted for military service, most of them had already had the equivalent of basic military training, were in excellent physical condition, and had been indoctrinated both with Nazi ideology and military attitudes. As a result, their training period as conscripts could move very rapidly through the preliminary stages; in two or three months the conscripts could take part in maneuvers involving divisions or armies.

Because of the work done by the Hitlerjugend and the RAD, the two-year (prewar) training in the army could advance much more rapidly and effectively. Furthermore, German boys had received good opportunities to practice and develop qualities of leadership, and officer material was already clearly marked out by the time they reached military age.

The training took place in the Ersatzheer (Replacement Army) before recruits moved on to the Feldheer (Field Army). The emphasis was on physical fitness; weapons training with marksmanship was an important component. The training lasted 16 weeks and included fire and movement, command, ballistics, heavy weapons, and tactical field training, map reading, fieldcraft, and camouflage.

Undoubtedly, the German Army of 1939 was well trained, well equipped and well motivated, its young men having been schooled under the Nazis; many of its officers were experienced soldiers. In the interwar period the Germans had embraced new technology and learned lessons from World War I in a way that the Allies - particularly the British - had not. The exigencies of war, however, meant that this level of training couldn’t be kept up and later in the war the standards weren’t as high.

The German Army itself had a very strong ésprit de corps that continued to the bitter end.

On March 15, 1945, the U.S. War Department produced a handbook on the Wehrmacht. Its opening section on the German soldier discusses their continued defiance in the face of defeat:

After five and a half years of ever-growing battle against ever-stronger enemies, the German Army in 1945 looks, at first glance, much the worse for wear. It is beset on all sides and is short of everything. It has suffered appalling casualties and must resort to old men, boys, invalids, and unreliable foreigners for its cannon fodder. Its weapons and tactics seem not to have kept pace with those of the armies opposing it; its supply system in the field frequently breaks down. Its position is obviously hopeless, and it can only be a question of time until the last German soldier is disarmed, and the once proud German Army of the great Frederick and of Scharnhorst, of Ludendorff and of Hitler, exists no more as a factor to be reckoned with.

Yet this shabby, war-weary machine has struggled on in a desperate effort to postpone its inevitable demise. ... Despite the supposed chronic disunity at the top, disaffection among the officer corps, and disloyalty in the rank and file, despite the acute lack of weapons, ammunition, fuel, transport, and human reserves, the German Army seems to function with its old precision and to overcome what appear to be insuperable difficulties with remarkable speed. Only by patient and incessant hammering from all sides can its collapse be brought about.

The cause of this toughness, even in defeat, is not generally appreciated. It goes much deeper than the quality of weapons, the excellence of training and leadership, the soundness of tactical and strategic doctrine, or the efficiency of control at all echelons. It is to be found in the military tradition which is so deeply ingrained n the whole character of the German nation and which alone makes possible the interplay of these various factors of strength to their full effectiveness.

The Germans, themselves, remember the morale of the last years of the war despite the propaganda aimed at them by the Soviets. General von Senger und Etterlin said:

I can only say the morale, in spite of these terrible losses and terrible times which we had to endure, was high. Which means we always felt superior to the Soviets. We always thought we were much better than they were. Our command and control was much better. Also, the single private soldier felt immensely superior to them as long as unit coherence existed and as long as the man was not completely isolated, lonely or something. It happened occasionally that these people lost their confidence, but very few were like that. Actually, there was absolutely no problem at all.

Truppenführung (Leading Troops)

This manual was published in two parts (in 1933 and 1934) and is often cited as a major contributor to German military success. It shows remarkable foresight, having sections on tanks and aircraft at a time when other countries hadn’t taken on board the lessons of World War I—in particular, the shock tactics used in the Michael offensive of March 1918. It isn’t an instruction manual per se, but a manual aimed at the NCO and junior officer that stresses the need for versatility; that the infantry officer must familiarize himself with the capacities of other arms than his own—a combined-arms view of fighting that certainly assisted the elements of Kampfgruppen (ad hoc formations of troops often collected from different services, or battle groups) to work together. It stresses that subordinates should use their initiative and provides a mission-oriented approach to leadership tactics— Auftragstaktik. There is little about strategy—something at which the German high command did not excel—or what to do when your command structure is compromised by heavy losses. It is important also to note that Hitler’s continuous meddling with low-level command decisions did much to negate the precepts of Truppenführung. These excerpts give a flavor of the work:

The conduct of war is based on continuous development. New means of warfare call forth ever changing employment. Their use must be anticipated, their influence must be correctly estimated and quickly utilized. Situations in war are of unlimited variety. Friction and mistakes are of everyday occurrence.

The teaching of the conduct of war cannot be concentrated exhaustively in regulations. The principles so enunciated must be employed dependent upon the situation. Simplicity of conduct, logically carried through, will most surely attain the objective.

The example and personal conduct of officers and non commissioned officers are of decisive influence on the troops. The officer who in the face of the enemy is cold-blooded, decisive, and courageous inspires his troops onward. Mutual trust is the surest basis of discipline in necessity and danger. The leaders must live with their troops, participate in their dangers, their wants, their joys, their sorrows. Only in this way can they estimate the battle worth and the requirements of the troops.

Superior battle worth can equalize numerical inferiority. The higher the battle worth, the more vigorous and versatile can war be executed. Superior leadership and superior troop battle readiness are reliable portents of victory. Troops only superficially welded together, and not through long training and experience, more easily fail under severe conditions and under unexpected crises.

The first demand in war is decisive action. Everyone, the highest commander and the most junior soldier, must be aware that omissions and neglects incriminate him more severely than the mistake of choice of means. Great successes presume boldness and daring preceded by good judgment.We never have at our disposal all the desired forces for the decisive action. The weaker force, through speed, mobility, great march accomplishments, utilization of darkness and the terrain to the fullest, surprise and deception, can be the stronger at the decisive area.

Time and space must be correctly estimated, favorable situations quickly recognized and decisively exploited. Every advantage over the enemy increases our own freedom of action. Rapidity of action in the displacement of troops can be assisted greatly or retarded by the roads and street nets and by the terrain conditions. The season, the weather, the condition of the troops, are also of influence.

The duration of strategical and tactical operations cannot always be foreseen. Successful engagements often proceed slowly. Often the success of today’s battle is first recognized tomorrow. Surprising the enemy is a decisive factor in a success.

The mission and the situation form the basis of the action. The mission designates the objective. The leader must never forget his mission. A mission which indicates several tasks easily diverts from the main objective. Obscurity of the situation is the rule. Seldom can one have exact information of the enemy. Clarification of the hostile situation is a self-evident demand. However, to wait in tense situations for information is seldom a token of strong leadership, more often of weakness.

The decision arises from the mission and the situation. Should the mission no longer suffice as the fundamental of conduct or if it is changed by events, the decision must take these considerations into account. Timely recognition of the conditions and the time which call for a new decision is an attribute of the art of leadership. The commander must permit freedom of action to his subordinates insofar as this does not endanger the whole scheme. He must not surrender to them those decisions for which he alone is responsible.

© Simon Forty and Richard Charlton-Taylor 2024, The German Infantryman on the Eastern Front (Casemate Illustrated). Reproduced courtesy of Casemate Publishers.

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

The WWII German Soldier has my utmost respect and admiration. Despite having sworn allegiance to a Depraved Maniac and his clique. He was a Soldier of the Highest Caliber, all we had were greenhorns who didn’t know how to fight.