'Naval Eyewitnesses'

The experience of men who served on the Cruisers of the Royal Navy - an excerpt from this wide ranging new survey of the Senior Service at war

Life in the Royal Navy was hugely varied during the war. From the battleships and aircraft carriers down to the submarines and smaller ships, trawlers and motor boats - each branch of the Senior Senior had its own character, and each of the many specialisms had its own outlook and character as well. This is reflected in James Goulty's comprehensive and rounded picture of the wartime navy - a rich and varied collection of personal stories.

Drawing on a huge variety of sources, he focuses on the experiences of individuals at every level of the service. Anyone with an interest in the Royal Navy will enjoy 'Naval Eyewitnesses: The Experience of War at Sea, 1939–1945', especially those with relatives who served in it during the war.

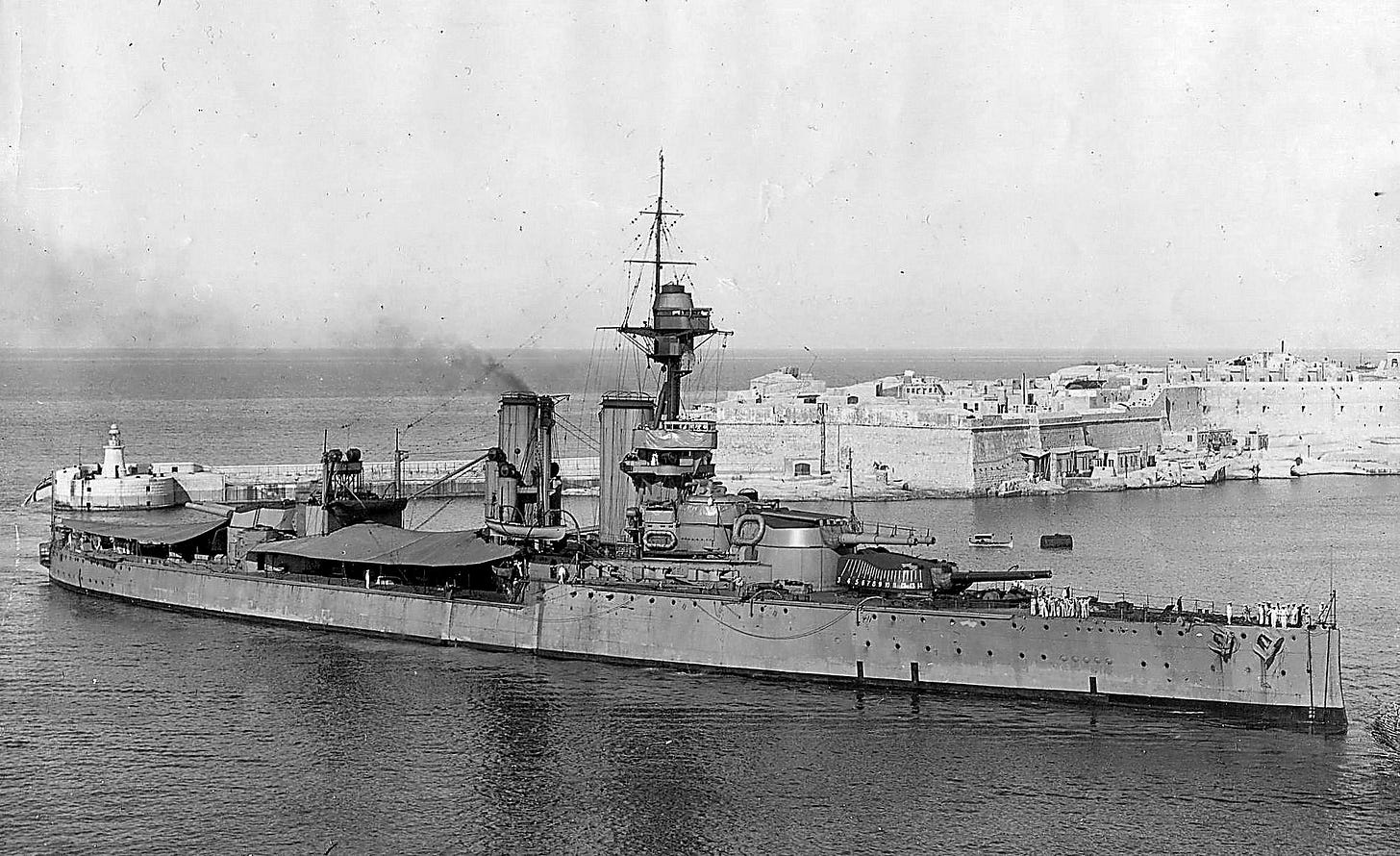

The following excerpt is from a section devoted to the Royal Navy cruisers, a relatively new class of ship at the beginning of the war:

As a result of the London Naval Conference of 1930, and in order to save money, governments made new treaty arrangements concerning warships. Accordingly, Britain changed from building heavy cruisers to developing smaller, cheaper ones armed with 6-inch guns, dubbed light cruisers. As war approached, a new series of light cruisers was introduced, and with the war - time additions of fire control systems and radar, these proved to be extremely capable, versatile warships, and served in all the major theatres: the Arctic, Atlantic, Mediterranean, Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Eric Hills was drafted to HMS Manchester as a young stoker in March 1941. She belonged to one of three groups of Southampton class cruisers built during the late 1930s, and saw action in the Mediterranean, where she was eventually lost. At the time Eric joined her, she was moored at Hebburn, and as he stood on the bank of the River Tyne and gazed up at her, he was in awe of the twelve 6-inch guns, plus an array of anti-aircraft weaponry. She was ‘the biggest ship I’d ever seen’ and ‘looked terrific with all those guns on it’.

According to one former officer who had served on HMS Hood and the light cruiser HMS Fiji, there was a difference in the atmosphere experienced aboard a cruiser compared with a battleship. ‘Life in a cruiser was much more informal. There were only, I think, six midshipmen in the wardroom, instead of about twenty-five or more in a battleship or battlecruiser, so we all knew each other pretty well.’

The Leander class cruiser HMS Ajax that famously took part in the Battle of the River Plate, when Graf Spee was scuttled, was ‘manned entirely by long service regular engagement officers and ratings; it would not experience any dilution of the ship’s company by reservist and hostility only officers and ratings’ until several months after the start of the war and after this famous naval victory.

Likewise, other cruisers gradually had more mixed crews. HMS Edinburgh, one of the third group of Southampton class cruisers, was a comparatively large ship with a complement of 850 men. As a young regular rating, specialising in radar, Commander William Grenfell was drafted to her in 1940, just after she had undergone a major refit in North Shields:

And she had been fitted out with the most highly developed long range warning RDF. That was my first ship. She was a 6-inch cruiser. I believe the largest cruiser type we had in the navy, there were only two of them built. One was the Edinburgh the other was the Belfast [now preserved on the River Thames] . . . The first thing that struck me was the discipline, and I liked it. I like discipline, I realise it is necessary, and I discovered that I had in fact by sheer accident, in a way I’ve the war to thank for this, that I had landed in the way of life that I really enjoyed most of all. A disciplined, clean way of life, with every opportunity for learning, we had instructor officers on board and even the higher ranked ratings, they all had an interest in the junior people, the PO and CPOs, you had every opportunity of learning as much as you wanted to. And I liked it.

A year later Colin Kitching joined HMS Edinburgh as one of the first draft of HO [Hostilities Only] ratings to serve aboard her:

About two dozen of us [joined] and we were the objects of enormous curiosity amongst these time-served professional sailors, and it’s interesting because to think I had just come down from Oxford, and expect I thought myself as quite a chap you know, but suddenly I found my real level there and I was a total nobody. I knew practically nothing. I mean the basic training was to get you disciplined and march properly and not look scruffy and so on, and you were taught a bit about knots and all that, but there was so much to learn and I was, well, the six months I spent on board Edinburgh were most remarkable, and yes, the remarkable experience of my life, and there is absolutely no doubt.

The professionalism of the whole thing was unbelievable, and I was so impressed with it, and I was so taken with the way I was treated and the rest of the draft. They regarded us as strange beings who knew absolutely nothing, which was true, and we had the mickey taken out of us, but they weren’t cruel and they weren’t horrible. They just regarded us as slightly half-witted young men who had to be taken in hand and make sure that we didn’t let the side down by doing something stupid when it mattered.

The one-time anarchist, connoisseur of surrealist art, jazz/blues singer, writer and critic George Melly spent part of his naval service as a rating aboard the cruiser HMS Dido, and captured the crew dynamic and the outlook of the different branches of personnel on such warships:

everybody in the ship’s company held a different if partial view. For the stokers and engineers it was the engine-rooms and propellers which signified; for the gunnery officers and ratings, the neatly stacked shells and turrets; for electricians, the ship was a nervous system of cables and power points; for the writers, a list of names, each entitled to different rates of pay; for the cooks, the galleys and store rooms; for the Master at Arms, rebellious stirrings and acts prejudicial to naval discipline; for the Captain and senior officers a view of the whole, detailed or vague according to their competence ... there were tensions, tolerance, fierce vendettas fought out with the aid of King’s Regulations or the sympathetic bending of the rules . . . [It was] a steel village. At first enormous and confusing, it soon became cosy, not as intimidating as a battleship, not as cramped as a destroyer.

Even so, not all ratings found the conditions favourable aboard cruisers. One who went to war with HMS Southampton commented that: ‘Food was awful, with very little of it fresh due to sea time. And each man’s living space became even smaller due to increased wartime complements and the need to pack in stores and new types of equipment.’

John Keller spent several years on HMS Glasgow as an artificer, and found that in cramped wartime conditions using a hammock was tedious owing to the amount of preparation needed to set one up, and then roll it up in the morning. Also the ship’s company had to be prepared to always carry gas masks and anti-flash gear [protective clothing] wherever they went, and the need to routinely be at action stations half an hour before dawn was draining. This was because ‘visibility suddenly increases at dawn, and you could be subject to surprise attack’.

As with a battleship, crews aboard cruisers had their own action stations. On HMS Fiji, Commander Owen, then a youthful midshipman, ‘was in charge of the anti-aircraft lookouts’, but changed positions when she came under a series of heavy air attacks that would lead to her sinking south-east of Crete on 22 May 1941. The navigation officer:

enlisted the midshipmen in turn; he called us there, I left my lookout and went to the bridge with him, and he said ‘I want you to tell me the instant the dive-bomber opens his bomb doors, because that means that the bomb will leave the aircraft, and I know that if I give the order, hard a-starboard, the ship will have swung sufficiently when the bomb hits the sea [that] it won’t hit us.’ Unfortunately, the first planes that attacked were not Ju-88s, which have bomb doors, but the Stuka Ju-87, which had a fixed undercarriage with the bombs carried under the wings. So the midshipman had to watch and see as soon as the bomb was clear of the aircraft and say ‘Bombs Away!’ whereupon Peter Norton [navigation officer] would give his orders and try to dodge it, dodge the bombs.

There were several near-misses, and then we were hit by a small bomb, and the effect of this is a terrific jolt, and you feel the ship shaking and vibrating, and you hear splinters from the bomb and bits of metal that have been blown off the ship rattling about, and of course, if these hit you, you could be killed or wounded instantly.

And after about two hours . . . we were firing the guns all the time. Great anxiety that we would run out of ammunition, which indeed we eventually did – I think we had something like 20,000 rounds of ammunition for the 4-inch guns. And all of that was expended in about eight hours, so you can imagine that continuous noise, continuous firing; all the time we were getting further away from Crete.

But eventually, sometime in the afternoon, we were hit – a very near miss, which caused one of the boiler rooms to flood. The ship stopped, all power was lost, and the ship started to list over to port, and then, looking up, I saw – I was back in the lookout position by then – I saw one plane approaching. I think it was a different sort of plane; it was a fighter-bomber, and I could see it had one large bomb underneath the belly, and he let it go, and there was no doubt that it was coming absolutely straight for us.

So all I could do, and anyone near me, was to fling ourselves on the deck with our heads down – we had steel helmets, of course – and the bomb hit somewhere aft in the ship. I didn’t actually see it hit the ship, as I was down on the deck, but we then heeled over even further, and the captain gave the order to abandon ship.

© James Goulty 2022, 'Naval Eyewitnesses: The Experience of War at Sea, 1939–1945'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd. The above images are not from this book - it does have a good selection of contemporary images - but they do not reproduce well here.

Recently on World War II Today …

'Big Week' hits Germany

Just as the Luftwaffe launched their final bombing campaign on London, the 8th Air Force began an intense series of raids on Germany. The sequence of raids from 20th-25th February in ‘Operation Argument’ were designed to attack not just the aircraft industry on the ground but to lure Luftwaffe fighters into engagements with the Allied fighters escorting the bombers.

Londoners adjust to a nightly 'Blitz'

The ‘ Baby Blitz’ now established itself as a regular nightly event in London. People had to re-accustom themselves to the business of air raid shelters, both indoors and outdoors. The Morrison shelter had been introduced in 1941, and despite its discomforts, had proven itself as a lifesaver. Considered rather more secure but less comfortable were the public shelters, in some places available on every street.