The Battle of Empress Augusta Bay

An excerpt from a new book that summarises all the 'Naval Battles' in the Pacific and Far East

The complex interactions of opposing ships during naval actions can be difficult to reconstruct. The perceptions of those involved at the time and reported in the subsequent action reports must be checked against the different charts of the ships’ movements. So summarising all the Naval Battles of the Second World War - Pacific and Far East in a format accessible to the layman is no small achievement. The following excerpt provides a sample of how this book approaches the task:

Battle of Empress Augusta Bay

BACKGROUND:

As American forces slowly fought their way up the chain of the Solomon Islands, the next target was Bougainville. Empress Augusta Bay, on the western side of the island, was selected as the landing point and the III Amphibious Force (TE31) was given the task of landing 14,000 men of the I Marine Amphibious Corps on 1 November. Carried in twelve transports escorted by destroyers and minesweepers, the landing operation went ahead smoothly against only light opposition.

However, Japanese aircraft from Rabaul were quickly on the scene with raids of up 100 aircraft continuing throughout the day. Although none were sunk, the transports were forced to withdraw that evening after unloading almost all the troops and supplies. The Japanese Navy was also quick to react and a scratch force of four cruisers and six destroyers set out from Rabaul with the intention of disrupting the landings before the marines could properly establish themselves ashore.

The task of guarding against this expected reaction fell to Rear Admiral ‘Tip’ Merrill with a force of four light cruisers and eight destroyers, the latter organised into two divisions led by Captain Arleigh Burke and Commander B.L. Austin.

THE ACTION:

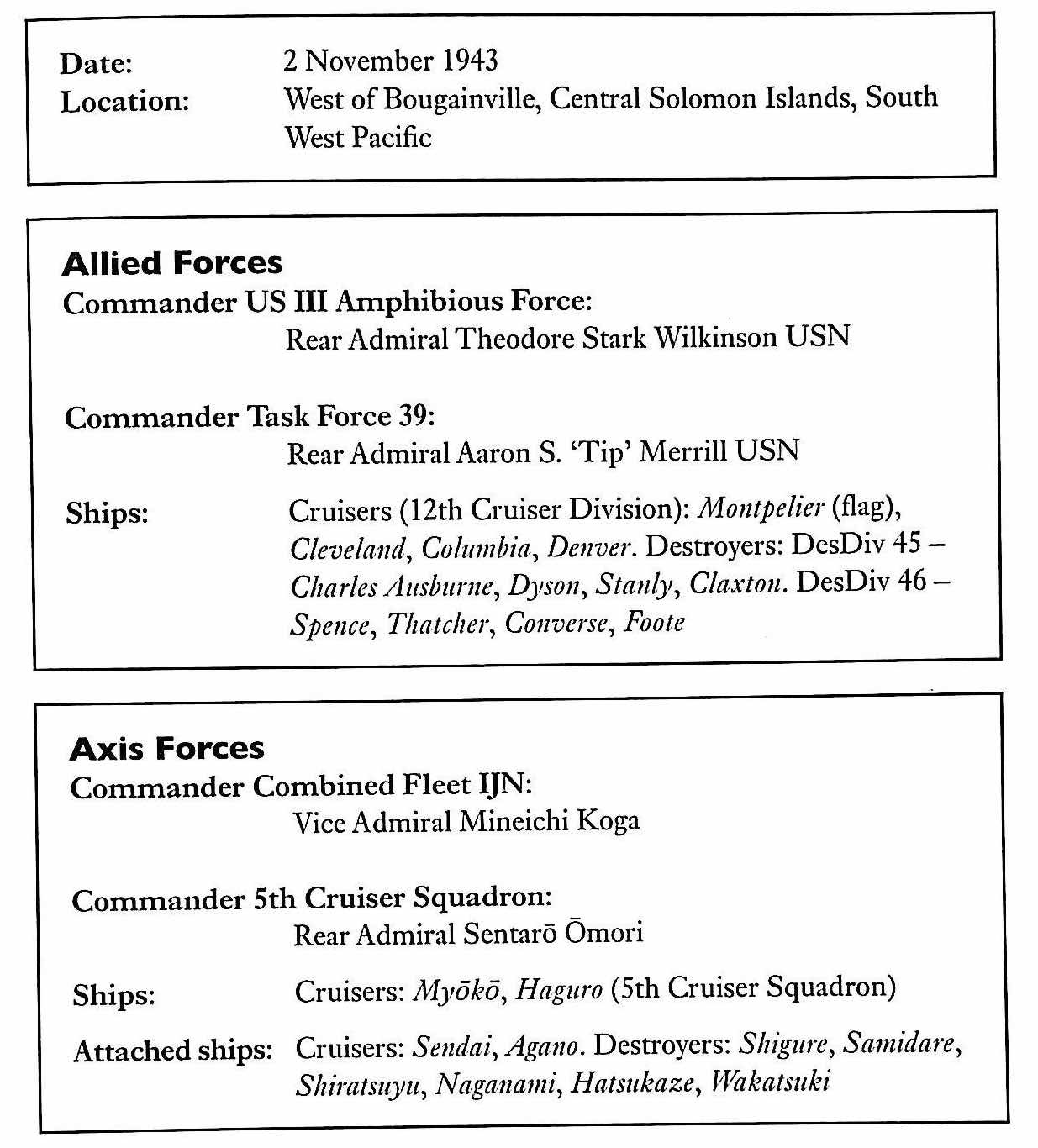

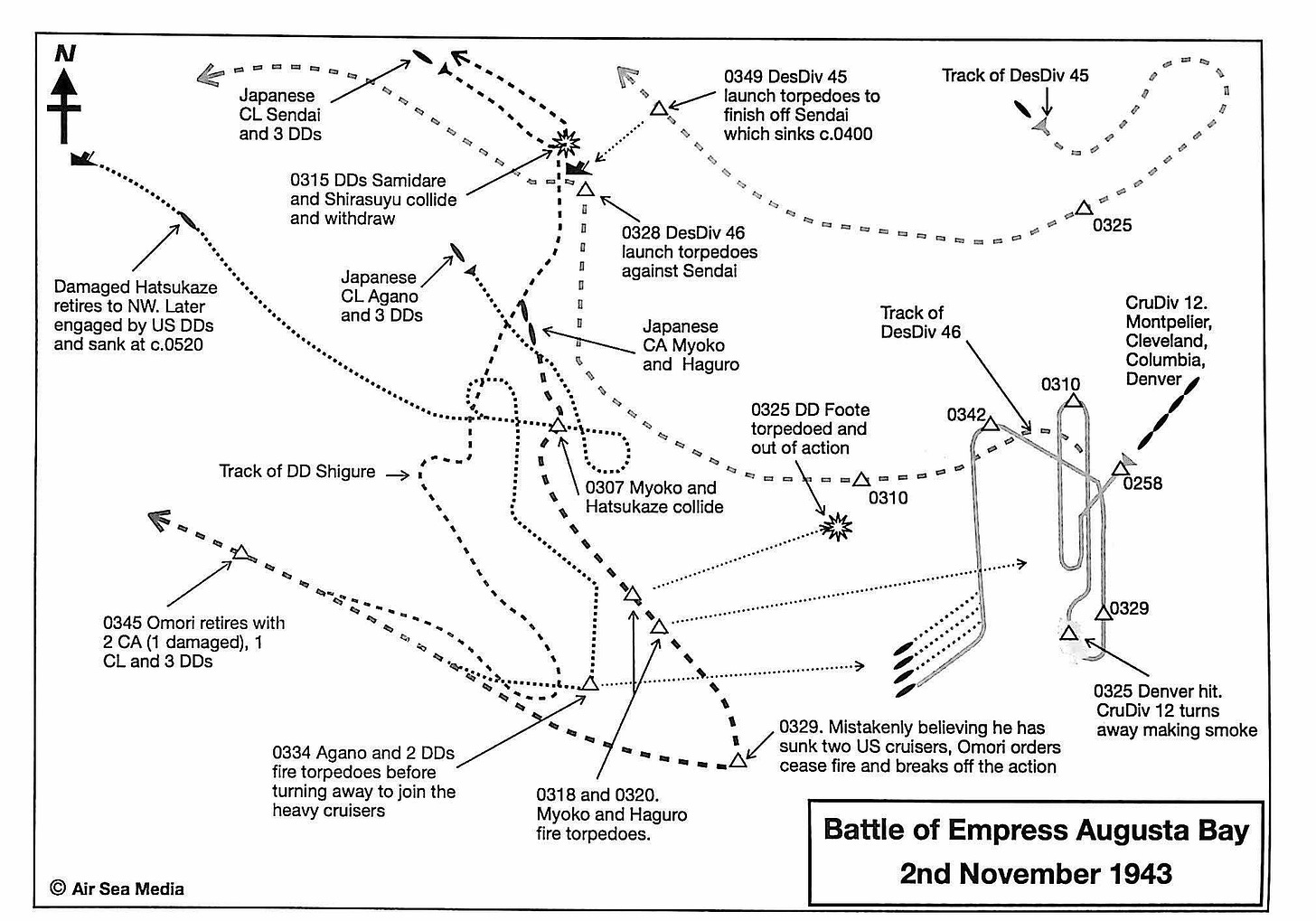

Merrill deployed his ships to the west of the landing beaches and at 0200 he was patrolling on a north-south axis. As they turned onto a northerly course, the Japanese force was detected on radar approaching from the north-west. Rear Admiral Omori had his ships deployed in three columns with his two heavy cruisers (Myoko, Haguro) in the centre. The port column consisted of three destroyers led by the light cruiser Sendai (Rear Admiral Ijuin) and three more destroyers led by the light cruiser Agano (Rear Admiral Osugi) to starboard.

Being now aware of the potentialities of the Long Lance torpedo, Merrill planned to push his destroyers ahead to attack while keeping his cruisers at long range to avoid the missiles. Both destroyer divisions accordingly attacked but their torpedoes all missed so Merrill now ordered the cruisers to open fire. These were all brand-new radar-equipped Cleveland-class cruisers, each armed with twelve 6in guns, and were capable of a high rate of fire. Throughout the engagement they manoeuvred as a single well-drilled team, despite running at 30 knots, and their concentrated fire was too much for the Sendai, which took several hits and was left with her steering disabled.

In manoeuvring to avoid the American gunfire, the destroyers Samidare and Sliiratsuyn collided, although damage was light. On the other hand, the heavy cruiser Myoko sliced into the unfortunate Hatsukaze and the destroyer was barely able to make her way off to the north-west. Eventually, Omori got his heavy cruisers back into line and they began to return fire but, although their fire was accurate, they achieved little against the fast-moving American cruisers.

Only Denver was hit and fortunately the shells did not explode. Merrill kept the range open by' tracing a figure-of- eight pattern through the calm waters and was not bothered by torpedoes fired by Myoko and Haguro at 0318. At one stage, the battle area was starkly illuminated by flares dropped from Japanese aircraft but these did not greatly assist Omori, who, convinced that he had sunk two of the American cruisers, ceased firing at 0329 and turned away to the west with the Agano and two destroyers in company.

After the first attack, Burke’s destroyers became widely separated and it took some time for him to round them up; by the time he had done so, the action moved on so that there was little left to do except put a couple of torpedoes into the damaged Sendai to finish her off.

Austin’s destroyers had initially been in company with the cruisers and as the battle hotted up, the Foote took a torpedo in the stern while Spence and Thatcher also came together in a glancing collision as they tried to avoid being run down by their own ships. At this moment the Japanese heavy cruisers passed by only 4,000 yards away but no torpedoes were fired as they were misidentified as friendly ships, a mistake soon realised as Spence was hit several times by shells from the passing cruisers.

By 0330, as Omori was breaking off the action, the American destroyers had the bit between their teeth and were pounding away to the north-west chasing Shiratsuyu and Samidare. However, Merrill was concerned that they would be caught well within range ofJapanese airbases at dawn if they continued on that course and ordered them to break off the pursuit. As they turned back, they came across the damaged Hatsukaze, which was finished off and sunk.

Merrill’s caution was well justified. As TF39 headed south in the early morning, they were attacked by over 100 aircraft from Rabaul but these only managed to put two bombs into Montpelier, causing relatively little damage.

In a good night’s work, Merrill’s ships had sunk a light cruiser and two destroyers while only Foote had sustained serious damage and she was successfully towed to safety. In stark contrast to many earlier night actions, Merrill had kept his cruisers under tight control and dictated the course of the battle, his tactics preventing effective torpedo attacks by the Japanese. He had, of course, fully achieved his objective of keeping the Japanese ships away from the landing force. As it transpired, this was the last major naval action in the Solomons campaign.

© Leo Marriot. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

For those wanting a succinct summary of the naval battles in the Pacific it would be hard to beat this volume. There are many narrative histories available - Naval Battles of the Second World War - Pacific and Far East would be an excellent companion volume to get a thorough understanding of each action. From Pearl Harbor and the sinking of the Prince of Wales, through Midway to the Leyte battles right through to the sinking of the Haguro in May 1945: each battle gets the same treatment - an exposition of what happened, a clear chart and a range of images.

This excerpt from Naval Battles of the Second World War - Pacific and Far East appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

N.B. Links to Amazon are affiliate links when accessed from the web (but not from the newsletter).