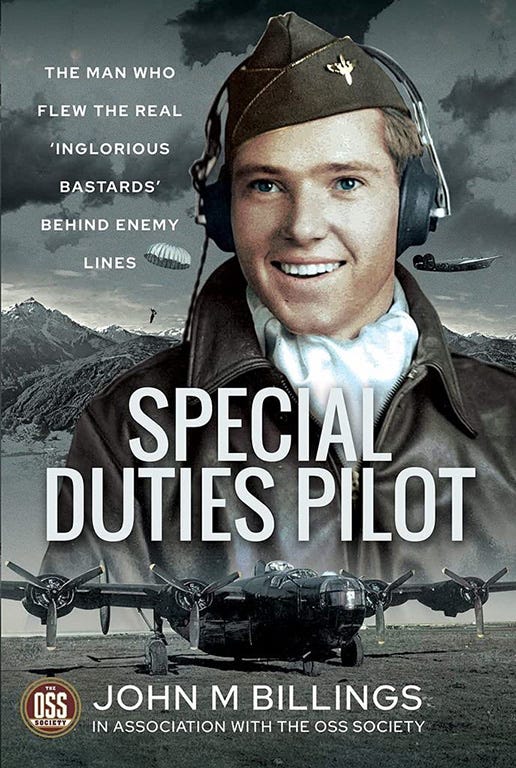

'Special Duties Pilot'

An episode from the life of an airman who found himself transferred from bombing to 'special duties' in a B-24 Liberator

The British had established the Special Operations Executive early in the war - as described in ‘Secret War’ - but the US intelligence gathering was spread across a number of agencies. President Roosevelt was concerned that they needed a more coordinated approach, and it was on the advice of William J. Donovan that the Office of Strategic Services was established in June 1942. The OSS rapidly expanded and was soon operating across a wide area of occupied Europe.

Inserting agents into the field required specialist aircraft and skilled pilots. They came from the US Army Air Force, with both aircraft and crew adapted for the purpose, learning from experience as they went

Special Duties Pilot: The Man who Flew the Real 'Inglorious Bastards' Behind Enemy Lines is very much the autobiography of a pilot and a natural storyteller. John M Billings describes a life of flying experiences that began in the seaside town of Scituate, Massachusetts. It was here that he got a three-year-old’s birthday treat in 1926, getting a ten-minute Air Ride in a small plane from a rough field. His destiny was set from this moment.

By November 1944 Billings had trained as a pilot with the USAAF, and had completed fifteen bombing missions in a B-24 from a base near Foggia, Italy. He and his crew were then mysteriously transferred to the “885th Heavy Special Bombardment Squadron” of the Fifteenth Air Force in Brindisi.

The following excerpt describes the extent of his “specialist training”:

It was only much later that we learned the 885th was a front for the OSS – Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. What we did know was that we wouldn’t be releasing bombs but supplies and agents dropped at low altitudes behind enemy lines. With people, we dropped to 600 feet. With materiel (military equipment and supplies), 300 feet. We didn’t rely on paper-documented altitude elevations. We relied on the radar altimeter on board to show us accurately how high we were off the ground. The device was very advanced for its time and is still used on some airplanes today.

Besides myself, there were my co-pilot, Roland; the navigator, Smitty; the bombardier, Dick; the flight engineer, Warren; and the radio operator, George. We rode in the back of a truck and arrived at the airfield in Brindisi (code name “Arise”) four hours later. Brindisi, located on the Adriatic coast of Italy almost to the heel, was about sixty-six miles south of the OSS headquarters in Bari, also on the coast. After settling into our new billets, we were assigned a side gunner named Daniel Halperin and a tail gunner, Jim O’Flarity. We were then briefed on the nature of our missions – to make strategic drops beyond the front to support resistance and Allied espionage efforts. Every mission had a code name, like “Slipway Yellow,” “Watermelon,” and “Pappy.”

To improve the success of our trips, we flew at night in the valleys of the Alps, with targets in Austria, North Italy, Yugoslavia, and Romania. We went on 100 percent oxygen at the start of each mission, even though we were flying low. This was because the oxygen improved our vision. We could see where we were going, and our navigation was excellent. Once, flying along in pitch-black darkness, we saw someone on the ground light a cigarette, and suddenly the entire compound below was illuminated by a single match.

We dropped parachute containers with food, leaflets, medical supplies, explosives, gold coins, and small arms. We dropped non-parachute items like clothing, tenting, and bedding that was bundled up and tossed out of the plane. And we dropped OSS agents.

The B-24 Liberator was modified for these clandestine operations. The olive drab was painted gloss black, then polished. Our crew even held Simoniz (wax) parties every month to polish the big bird. Because we were flying at night, we needed to be invisible to enemy searchlights, and the black paint did a good job of it, unlike the irregular texture of the flat olive drab that caught every point of light in every part of the plane. Another alteration was removal of the ball turret, making a well where the agents sat – in our case, no more than three per mission – until they were tapped to go. The space was walled in with smooth metal to avoid any snags.

After arriving in Brindisi, we had only two days of training. On the first day, November 27, we were sent on a practice run with a bombardier from another crew who was considered the expert, with more missions logged than us. He gave us pointers on how to get parachutes and free drops to their intended destinations. Standing behind Dick, who was riding in the front turret, the bombardier in charge gave instructions over the intercom, saying, “The first time, we’ll just do a low pass.”

OSS agents were called “Joes,” except for a “Josephine” who flew with us once, and we never saw their faces. These measures to conceal their identities were taken in case we were captured by the Germans and ordered to reveal their names.

He gave me right and left cues to position the airplane where he wanted it and set the distance for parachutes at 300 feet. “A little lower, a little lower,” he said, relying on visual recognition instead of an altimeter reading. When he said, “Okay, this is a good place. Let’s go around and do a dry run,” I made a big racetrack pattern to lose altitude and went back to reposition.

Dick, who would be giving the drop command during an actual mission, nodded his head and said, “Now!” The timing and positioning satisfied our expert trainer. “Very good,” he said. “Let’s do it for real this time.” By “real,” he didn’t mean we’d be dropping anyone or anything, but just simulating an actual mission.

Dick gave the okay for the trainer to open the bomb doors. On an authentic mission, Dick would have done the job, but because he was inside the front turret, he didn’t have access to the bombardier’s controls. “Make a racetrack pattern,” Dick said, so I peeled off to the left, bringing us out over the Brindisi harbor. This was a highly active seaport where materiel was coming in for the British.

We had descended to about 250 feet over the water when suddenly I heard a loud “wham!” and looked back to see the bomb doors flapping. The load was gone – the small arms munitions intended for the underground on our next mission, which was to be that very night! The “experienced” bombardier had accidentally yanked the emergency salvo lever, releasing the explosives that landed on a British warship!

Fortunately, no one was injured, but it created an international incident and drew a profuse apology from the bombardier, who should have known his right from his left. Needless to say, we didn’t fly that night.

Two days later we had another practice drop. This one went smoothly. That was the extent of our training, the sum of our preparation for the dangerous and critical missions ahead.

OSS agents were called “Joes,” except for a “Josephine” who flew with us once, and we never saw their faces. These measures to conceal their identities were taken in case we were captured by the Germans and ordered to reveal their names.

During the approach to the drop zone, the dispatcher, Jim O’Flarity, who was also my tail gunner, would stand behind the agents sitting around the “Joe Hole,” as it was called, and discuss the order they’d be going in. On the bombardier’s signal, Jim removed the plywood covering the hole and tapped the agents to exit as quickly as possible so they’d get ahead of the supply parachutes we would be dropping in the next pass to avoid any entanglement.

We flew away, then returned, watching for the signal that told us the “Joes” had made it down safely. Then we released the supply parachutes.

This excerpt from Special Duties Pilot: The Man Who Flew the Real 'Inglorious Bastards' Behind Enemy Lines appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

Thank you for reading World War II Today — your support allows me to keep doing this work.

If you enjoy World War II Today, it would mean the world to me if you invited friends to subscribe and read with us. If you refer friends, you will receive benefits that give you special access to World War II Today.

How to participate

1. Share World War II Today. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

2. Earn benefits. When more friends use your referral link to subscribe (free or paid), you’ll receive special benefits.

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 15 referrals

To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.

Thank you for helping get the word out about World War II Today!