Wartime lives revealed in letters home

This excerpt features a 'typical' GI in Italy and France 'wounded nine times'.

Clement Horvath became interested in the war when, as a child in France, he met a badly wounded former member of the resistance. The realisation of the lasting effects of war on ordinary men led to a long term project collecting the letters of servicemen writing home. From hundreds of different servicemens’ letters he has selected a small percentage to represent every phase of the war in Europe from 1939 to 1945.

American, British, Canadian and French servicemen are all represented in ‘Till Victory - The Second World War By Those Who Were There’.

The following excerpt has been chosen almost at random and illustrates the way Horvath has set every letter within the context of the military action in which they were participating. It also shows the considerable research he has undertaken into the lives of these men - right through to the post war years.

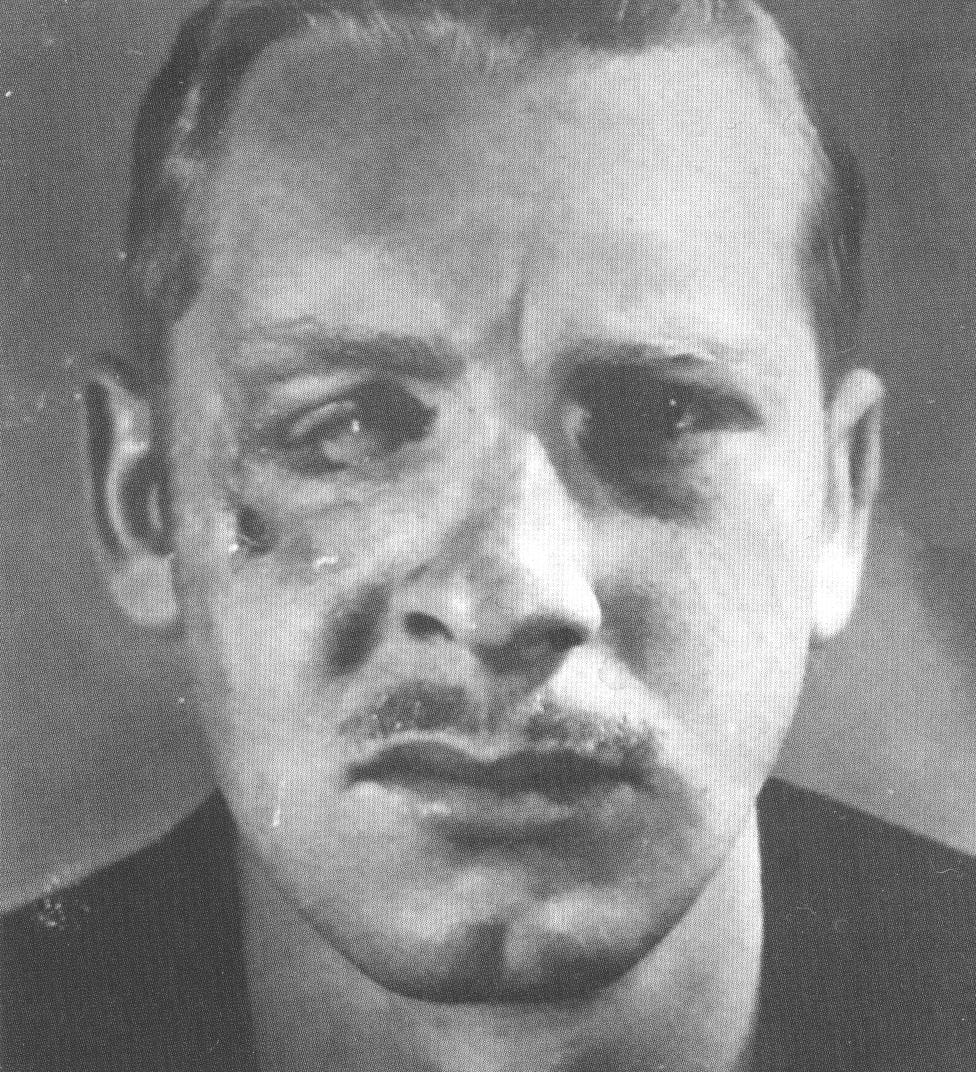

Joseph Charles Nemec Jr. was a 19-year-old New Yorker when he arrived in Italy as a replacement. His 7th 'Cottonbalers' Regiment (3rd Infantry Division) is already very experienced, having been among the spearheads of the landings in Africa (November 1942) and Sicily (July 1943).

Joe is a radio operator (a job he learned the basics of in high school) and carries the heavy communication equipment on his back, sometimes in the middle of the fighting. After a stopover in North Africa for a few days, passing through Gibraltar, Bizerte and Malta, the Mediterranean crossing wasn't easy as his convoy was attacked by the Luftwaffe and German submarines.

Two Allied ships were sunk, but Joseph's made it out alright, even shooting down two planes during the attack. Joe saw Naples and Mount Vesuvius, but couldn’t taste the famous 'pizza pies' he’d heard so much about (and which aren’t yet known to many Americans): the Italians no longer make them because flour and oil have become too rare.

Joe suffered from dysentery anyway, and was hospitalized for two weeks at the end of 1943. He's sent back to his company on December 28, just in time for his first action. Joe is about to experience his very first amphibious assault on January 22,1944, in Anzio.

…

OPERATION SHINGLE

Supported by Rangers of the 1st, 3rd and 4th Battalions, who invaded Anzio Harbor, and paratroopers of the 504th and 509th Parachute Infantry Regiments, the 1st British Infantry Division lands on Peter Beach, north of Anzio, while Joe's 3rd US Infantry Division sets foot on X-Ray Beach, east of Nettuno. The surprise is total and the opposition minimal. Of the 36,000 men who land, only 13 soldiers are killed and 97 wounded. But things won't go so well a few days later.

[The Allied troops at Anzio were soon surrounded by German troops on the higher ground lying inland all around them]

…

BACK IN THE HOSPITAL

On February 1, fighting intensifies in front of Cisterna, and Joe's regiment, alongside the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 4th Ranger Battalion, launches a failed assault. Joe is shot by a German machine gun through both buttocks. Two days later, he writes to his parents in three different V-mails:

“Dearest Mother & Dad, Well hello there, folks, how are you all? I do hope that you folks are alright and in the best of health and everything is okay at home. I hope you were not worried when you did not hearfrom me for a couple of weeks.

You see I didn't have a chance to write you and tell you that I wouldn't be able to write for a while. You see we had to go on the move again, as you read about the invasion recently made below Rome. Well I can say I saw my first invasion, maybe you wouldn't call it an invasion because we didn't get any German opposition. Although the British took prisoners as you read about It. What did you think when you received the newspapers and read the headlines?

Well I guess I might as well give you a little sad news, because the army will notify you anyway:

I’m in the hospital again, not the dysentery this time. I got hit by a Jerry machine gun bullet. I bet you can't guess where I got it. I got it right plump in the buttock, in other words the priddle. ha ha. But don't go worrying now, it's nothing serious and I'm coming along swell, only I can't sit down. I'll probably be good for a months rest anyway. [...]

The bullet hit both cheeks and just sliced it as it passed, it didn’t go in. What a feeling it was, as if somebody cracked a whip across my rear end and the first thing I hollered out was och you dirty S.O.B. Nazi!

Well no use wasting paper telling the details I'll tell after the war when I come home. Anyway, here I am back in a nice soft bed again, clean sheets instead of a dirty old slit trench to sleep in with a pack as a pillow. They're giving me a Purple Heart [Medal] for being wounded, but that doesn't do me any good as far as getting home. The only thing that's good for is to stick it in the drawer and keep it as a souvenir after this war. [...]

I'm continuing in letter no. three now. Gee, these 'V'mail are a pain in the neck no kidding. You just about start and then you are ready to sign off again. [...] Boy was I embarrassed last night when the nurse had to dress up my wound on my priddle. And then this morning she came around to wash my legs, feet and back because I couldn't bend down to get at them. Boy what service no kidding. That's something I didn't even let my Mother do, ha ha, I'm only kidding you Ma! [...] Well folks I hope you're all okay, and I probably write tomorrow. Love, Joe."

Joe will spend several more weeks in the hospital. On February 18. he receives his Purple Heart on his hospital bed: he thinks it's a beautiful medal. But he suspects that as soon as his wound has healed, he'll be sent back to the front. His roommate is able return to the United States, but he's no luckier: the poor 19-year-old man was shot by a German sniper who tore off part of his spine, making him lose the use of his legs.

For Joe, however, it's always preferable to the horror of combat: "I'd sure go through what he went through to get to go home. You probably don't agree do you?" Joe has to go back to the front in March.

He then writes in a V-mail to his father:

"Dad you said that they should send the fellows home to recuperate well they do sometimes, if he has a leg or an arm shot off or wounded bad enough. But they try to patch you up as fast as they can and send you back to duty. Just a piece of equipment or machinery. They don't think much of a man's life, as long as they win a battle!"

…

JOE’S RETURN

When Joe goes back to his comrades in Anzio, they hadn't moved an inch. The 150,000 Allied soldiers now in the area won t be able to leave the German encirclement until late May 1944, after the crossing of the Gustav Line in the south. Breaking through the pocket won't be without damage, though, and on May 23, the 3rd Division will number 955 casualties in a single day, a sad record for all US Army divisions during the Second World War. Cisterna, the city where Joe was wounded in early February, will finally fall into the hands of his division two days later, where it will destroy the 362 German Division that had refused to surrender.

Like tigers kept in cages for too long, the Americans will crush everything in their path. On the same day of the breakthrough, four men of the 3rd Infantry Division will be awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest American military distinction. The division will then reach the outskirts of Rome, and Joe, with his 1st Battalion of the 7th Regiment, will have the honor of being among the first liberators to enter the capital on June 4.

However, this is a very small reward for the Cottonbalers, who suffered more than 3,000 casualties during the Anzio-Rome Campaign, including 729 killed, or a complete turnover of the regiment. A total of 7,000 Americans and British died at Anzio and Nettuno, and 36,000 were wounded.

…

FRANCE

[Joe then took part in the landings in southern France in August 1944 and the subsequent rapid advance north through France.]

In mid-October. Joe completes four days of training in Eloyes, where his unit receives replacements to fill the gaps in the ranks. He takes this opportunity to write to his parents again on the 17th:

"About another week and I'll be with this outfit one year; gosh did that time go by fast. I'm the third oldest man in the radio section, so I can call myself an old man in the company. Because a few went home on rotation and some was [sic] killed or wounded. Naturally that dwindles them down to us year aiders. I sure would like to go home with this outfit, because I'm pretty proud of this division. I suppose though when we do come home the civilians will praise and cheer us, but shortly afterwards those who fought overseas will be forgotten; just like in the last world war. Half of them should come over here and just see what really is going on, and what we are going through to get this war over with."

Despite the fatigue, by October 20 Joe has to return to the front lines. The regiment leaves Grandvilliers for the Col du Haut Jacques, west of Saint-Die: a strategic crossroads for both sides, which the Germans really don't want to let go.

The American assault, part of Operation Dogface, is intended to help the VI US Corps break through the Vosges to Strasbourg. Men often fight at close range in difficult weather conditions and with almost no visibility. Joe, who carries the radio for Major Benjamin C. Boyd (the battalion commander), would play a crucial role in the battle, as communications are essential for the troops' progress in the rugged terrain of the Vosges.

As night attacks are common, good coordination between units is necessary to avoid the many traps laid by the German 120 mm mortars, artillery, 88 mm guns, camouflaged machine gun nests, anti-tank and anti-personnel mines, booby traps (explosive devices often triggered by an invisible wire), road blocks and ambushes, all lie in wait for the Allied forces.

Joseph is wounded again in the first days of the attack, somewhere between Les Rouges-Eaux and the Col du Haut Jacques. Sheltering in a small barn, his small group ol radio operators is about to cook a pasta meal when, suddenly, the German artillery scores a direct hit. A fragment of the wall fractures Joe's cheekbone and damages his right eye.

On October 29. as the fighting in the mountains continues (Le Haut Jacques wouldn't be secured until November 4), his sergeant writes to Joe's parents:

"I suppose you have heard by now that Joe was hit again. He will be OK but I sure miss him. He was one of my best radio operators and as a soldier he couldn't be best [sic]. That son of yours was the coolest kid I ever saw. He never got excited. One day he ran into some Jerries. He pulled out his .45 and shot him out of things. When he came back he wasn't excited at all. All he said was 'You should have been with me!'"

Joe also announces the sad news to his parents on November 8:

“I'm afraid I won't be too pretty a sight to look at when you do see me, as I got it pretty bad this time. This makes it nine times I've been hit and remember the old saying a cat has nine lives. I'll have a pretty bad scar on my right cheek and I'll probably lose the sight of my right eye and hearing of my right ear. Otherwise everything else will be okay. I was one of six that was wounded and I was hit the worse. Two of the other men that was [sic] hit were radio operators. I was lucky I didn't get it sooner as we had some days that were pretty hot. You'll notice the 'Sgt.'up there in front of my name. Yes, I made T4 the same day I was hit.

I met Major Boyd, my Battalion Commander, here in the same hospital. I was lying in bed and he comes walking up to me and he sure was surprised to see me here. He's really a swell man to know; I was with him quite often, as I carried the radio for him."

…

RECUPERATION AND POST SERVICE LIFE IN THE USA

While undergoing months of rehabilitation at William Beaumont Hospital in El Paso (Texas), he'll meet his future wife. Alice, who was a secretary in the hospital. They'll have three daughters and live in Elmhurst. New York, but Joe's life will never be the same again.

Mutilated, and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and alcoholism, he'll no longer be the funny young man he was before the war. These issues will cost him his marriage, and Joe will be in pain for a long time. The loss of his eye (replaced by a glass one), will prevent him from working as an engineer, as he had always wanted to. He'll become a repairman instead, and the asbestos contained in the appliances he services will lead to cancer that will take him away on October 28 2009.

Joe rests today at the Long Island National Cemetery in New York.

This excerpt appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author.

The strength of ‘Till Victory - The Second World War By Those Who Were There’ lies in the diverse range of experiences represented and the context in which they are presented. The extensive research undertaken into the lives of so many different men is a rare achievement and makes their stories all the more compelling. Clement Horvath has produced a fine memorial to a generation of men. It is worth quoting from his introduction:

The first family found was of Ray Alm, an elite American soldier from the 2nd Ranger Battalion, who landed on Omaha Beach. His son Rick, who unfortunately lost his battle with cancer on February 16.2017, was an extremely kind man and interested in my project. As a great journalist (and a Pulitzer Prize winner), he always had a good anecdote to tell about his father.

One of them was about the secret language that Ray and his wife Audrey had developed. Censorship didn’t allow Ray to reveal his location, so he used his signature in a clever way closing his letters with “With love" meant he was in England, "All my love’in Scotland and France was “Lovingly". Not knowing where he would go, they prepared many codes in advance for countries such as Italy, Japan, Russia, Australia, and even Guatemala or Somalia. As you've probably guessed, 'Till Victory’ was the signature for Germany.

His son's kindness and trust gave me the courage to find more than forty other families. Before Rick sadly passed away in 2017, I promised him that the title of the book would honor his father.

Beyond the anecdote, Till Victory represents optimism and determination, while carrying the uncertainty that this horrible war could bring to two young lovers' lives. The title perfectly sums up the content of the book: hope and fear, love and sacrifice, the home and the front, "until victory”.