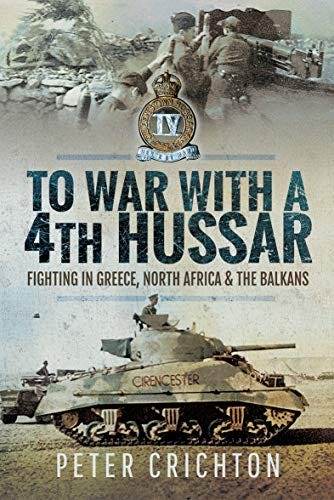

To War with a 4th Hussar

An excerpt from a recent new memoir, covering the armoured pursuit of Rommel's forces in North Africa following the breakthrough at El Alamein

Personal perspectives on the war continue to emerge. Peter Crichton did not begin writing his memoir To War with a 4th Hussar until 1969. He completed a typescript but then went no further. It was left to his son, Robert Crichton, to arrange publication in 2019. This is a vividly written account of four and a half years overseas, despite being written from memory.

As the subtitle suggests - Fighting in Greece, North Africa & The Balkans - Crichton had an eventful war. When war broke out he immediately volunteered for the Northamptonshire Yeomanry - but transferred to the 4th Hussars when he learnt that they were bound for the Middle East. He had a lucky escape from the British Army’s short lived adventure in Greece before participating in the major battles in North Africa. Written with the benefit of hindsight he intersperses his personal memories with a good degree of context - the capabilities of the Army at the time and the strategic objectives - which makes this a particularly accessible study.

As one of the few surviving officers from 1940 in his regiment he appears to have fallen out with a new commanding officer in 1944. He then found himself advising the partisans in Yugoslavia on armoured warfare. The ‘armoured’ part of this did not last long - but he became fully engaged in partisan warfare.

The following excerpt covers the period in November 1942 when the British Eighth Army began their pursuit of the Germans in North Africa following the breakthrough at El Alamein:

On 7 November there was a heavy rainstorm which slowed down the infantry and our own echelons, and we pushed on alone. We reached the tarmac coastal road, which enabled our tanks to reach their maximum speed, and tve now tore along to the west in hot pursuit.

We ran straight into the German rearguard at Sidi Barrani.

The Colonel’s voice, distorted by the crackling headphones of the wireless, gave us the order to attack. Archer and I had agreed that we would hunt like a pack of hounds, closed up and as fast as we could, to exploit the speed of our tanks and to concentrate the firepower of our small calibre guns.

We swung off the tarmac road into the dunes to the south and turned west, heading straight for the enemy. Anti-tank gun shells smacked into the sand as we drove over one crest after another. Within minutes we were right into the enemy’s position, all guns firing. German infantry were running hither and thither, some with their hands up, some still resisting. It was the confusion of close battle.

What were we to do, kill them all? It was impossible from a tank to select one man over another for execution. I could scarcely answer the Colonel as I heard his voice on the wireless, and shouted for my pistol as Ramcke parachutists, many with their hands up, came within yards of my tank.

We were now right behind the enemy position and turned to attack their rear. Less than a hundred yards away, an anti-tank gun crew were desperately trying to turn their weapon to fire. They had almost carried the trail round and were dropping it. One of our troop leaders was just in front of Archer’s tank and mine, and he was standing high up in his turret laying his gunner’s aim as if on a practice shoot. My brain froze in fascination at the spectacle. Who would fire first? Then the small solid shot from the 37mm seemed to spit into the sand close to the gun trail, and the gunners’ hands went high above their heads in surrender.

I called to the Colonel to bring ‘M’ Battery RHA into action, and within minutes their 25-pounders were laying a barrage of gunfire upon the defenders. However, by now we were isolated behind the enemy, and I was uncertain of the position of one of our troops and had to ask the RHA to hold their fire.

But the enemy rearguard were now broken, and those who had not surrendered were pulling out with their vehicles on to the road. ‘M’ Battery opened up again, but within minutes, or so it seemed, the battle was over.

Squadron Sergeant Major Hoyle appeared, his tank festooned with prisoners, some clinging to his gun barrel, excellent insurance against a sneaky hand grenade. In this action we had suffered only relatively light casualties thanks to the speed of our attack and our concentration, but sadly we lost one of our best troop leaders, Lieutenant Tony Cartmell, who was killed; his crew were killed or wounded.

We continued the pursuit towards Sollum at high speed but we were getting short of petrol. The Colonel called a halt on the road, but Mark Roddick, the Brigadier of the 4th Light Armoured Brigade, turned up with a Royal Air Force tanker full of high octane fuel. He asked if our tanks would S° on this super stuff, and we were able to assure him they would go all the faster.

Contrary to all custom, Archer and I were leading the squadron with one headquarters tank in front as in the late evening we arrived at the bottom of Halfaya Pass.

Without a pause the Colonel ordered us to go straight up. had got half way when there was a terrific explosion, which I thought at first was shellfire, and I wondered how we should fare if the enemy had such heavy guns on top of the escarpment; but it was a double Teller mine, which had blown the bottom out of the leading tank under the driver’s feet. The man was badly wounded, and the crew carried him to put him on top e engine cover of my own tank, crying out with the pain of his damaged legs.

Though I have always had a horror of injections, I was forced to the jab needle of the morphine capsule into his arm which almost immediately quietened him.

Douglas Nicoll, always somewhere close to hand, trudged up the pass in the dark over the mines with a stretcher party to collect the casualty.

I could scarcely believe I was alive; only the back of my left hand was bleeding. The spot where the mine had been buried was the exact position where I had slept.

We were now well and truly stuck, since we could not go forward or back. We knew not if the enemy were waiting for us on top of the escarpment, but there was no action we could take until the mines were cleared, so we attempted to sleep by the side of the tanks on the gravel of the road.

Some time during the night, I was woken from my uneasy slumber by a New Zealander sapper who prodded the ground where I had lain and passed with his bayonet, shoving it in at an oblique angle rapidly in front of him as we walked.I would not be a sapper for a million pounds, and I have always thought they must have nerves like steel. We had undergone a course in the defusing of mines, and I had always prayed that I would not be called upon to put my lessons into practice.

With the dawn, Hell Fire Pass was apparently cleared of mines, and the New Zealand gunners hastened to climb the escarpment, passing the damaged tank which was blocking our way by using a narrow lane marked, as was the custom, by white tape. There was scarcely room to squeeze by, and as the first portee approached I stood in front of my tank to prevent the driver from fouling my tank tracks with the nearside wheel of his gun.

As the hub narrowly scraped against the track, and I was furiously shouting at the driver, who had pressed away from the dangers marked by the tape, there was a terrific explosion. The wheel of the gun disappeared as a double mine blew it off.

I was almost completely deafened. My driver, who had been standing at the rear, was wounded in the face by the sharp gravel blown sideways by the blast. I could scarcely believe I was alive; only the back of my left hand was bleeding. The spot where the mine had been buried was the exact position where I had slept.

Archer asked me how I was after my narrow escape, to which I replied that I was white and shaking. It was a standard joke between us, but in point of fact not far from the truth on this occasion. I have been deaf in my left ear ever since.

This excerpt from To War with a 4th Hussar appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author. The above images are not from this book - it does have a good selection of contemporary images and maps but they do not reproduce well here.