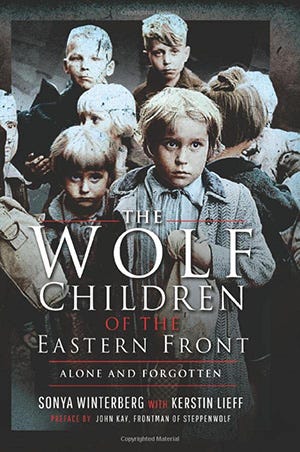

The Wolf Children of the Eastern Front

A new study of the fate of children caught up in the death march out of Prussia

This week’s excerpt looks at the fate of German children caught up in the mass evacuation of Prussia as the war drew to a close. In The Wolf Children of the Eastern Front - Alone and Forgotten Sonya Winterburg and Kerstin Lieff have gathered together dozens of accounts of survivors from the invasion of East Germany by the Red Army in 1945.

In the ensuing chaos, it is estimated 20,000 children lost their families, children who watched helplessly as their siblings starved to death or their mothers died from illness or simply from exhaustion. These children, suddenly finding themselves alone, formed bands that wandered the countryside of East Prussia and Lithuania for months and even years.

The true impact of this episode cannot be understood in numbers - only by the experiences recorded here. Some are short, some quite a bit longer, some have a happy ending, many do not. By the nature of the fact that these are survivors’ tales, we may take some comfort. But so many of them contain the stories of family and siblings who did not survive.

From the preface by John Kay, the frontman of Steppenwolf, :

I've always considered myself to be fortunate but, after reading this gripping I book of horrific and terrifying tales about the lost children and orphans left behind in East Prussia in 1945, I now know how truly lucky I am.

Had it not been for the death of the father I never knew, my mother and I would have remained in Tilsit and been forced to flee East Prussia to escape the advancing Russian army, like thousands of refugees who died of hunger and cold or worse during their desperate trek in pursuit of safety. It’s doubtful that I, as an infant, would have survived such a deadly ordeal.

….

My father, who was in the German army, was killed on the Russian front a month before my birth. Because she was now a ‘war widow’, the Nazi authorities permitted my mother to take me and travel by train to ‘visit’ my paternal grandmother.

…

It is difficult to put into words this bizarre, unnatural feeling that my father’s premature death is why my mother and I survived and were spared the horrors of the death march out of East Prussia in 1945.

During the final months of the war, thousands fled East Prussia to escape the advancing Red Army. Some in horse-drawn wagons piled with people and scant possessions, others on foot with just a suitcase and their children in tow, struggling to keep up.

Through freezing temperatures and blowing snow they trudged endlessly in a frantic attempt to reach safety. The escape route soon became a highway of horrors: women throwing babies onto vehicles; dead horses lying frozen in the road; human corpses in the roadside trenches. All this with pounding artillery filling the air.

In the ensuing chaos, it is estimated 20,000 children lost their families, children who watched helplessly as their siblings starved to death or their mothers died from illness or simply from exhaustion. These children, suddenly finding themselves alone, formed bands that wandered the countryside of East Prussia and Lithuania for months and even years.

They lived in forests and fields, hid in bullet-riddled farmhouses, and begged for, or stole, what food they could find, some no older than 4, often carrying a younger sibling on their hips. Those who managed to survive were mostly saved by Lithuanian farmers. Today they are known as the Wolfskinder or Wolf Children. This is their story, a story which has touched me like no other I’ve read in years. If it doesn’t move you, I suggest you check your pulse.

John Kay (born Joachim Fritz Krauledat, 12 April 1944) is a German-born Canadian rock singer, songwriter and guitarist known as the frontman of Steppenwolf, whose signature hit is ‘Born to be Wild'.

The following are just two short recorded experiences from this collection:

Ursula Hundrieser was born in Konigsberg in 1933. Memories of her father fade fast after he left for the war, and her older brothers were all killed. Who’s left of the family is Ursula, her mother and her younger brother.

When the Red Army invades East Prussia, soldiers burst into her home and rape her mother in front of the children’s eyes. Life becomes unbearable; the family is plagued by typhus and famine.

When her mother continues to decline, Ursula decides to bring her, a now fully incapacitated woman, to the army hospital. But the doctors don’t give her much hope. Six days after she is admitted, her mother dies. Ursula is not even able to say goodbye. The doctors won’t allow her into the room as they fear she could become infected.

Ursula’s little brother, just turned one, also soon dies of starvation. His dying is torturous, and it nearly drives Ursula mad. His little stomach is bloated from malnutrition, and the baby cries incessantly and fusses without end. When he’s finally dead, Ursula is relieved. She buries the little one in a mass grave, and only then does it dawn on her that she’s now all alone in the world.

Barely 12 years old, Ursula flees to the nearby forests of Lithuania, where she begs and, when necessary, steals. One day she’s taken in by a farmer’s family and she hopes that now everything will become better once again. Even though the work in the household is hard and cattle herding is difficult, she endures her new life without complaint.

Life feels whole again, and she’s nearly forgotten what brought her to this land where she’s a foreigner, when one day out in the pasture a horse rears up in front of her and kicks her hard with his hoof. Ursula is badly injured. In the hospital, she’s not regarded as a member of the Lithuanian family that brought her there, but rather as a German.

Despite the farmer’s ardent pleading, the Soviet military doctor refuses to treat this ‘fascist child’. He even forbids the nurses, who are otherwise compassionate, to bandage her bleeding wound.

Because the scared farmer fears repercussions for his own family, he leaves Ursula by herself in the hospital. Even though she’s in tremendous pain, she tries to find her way back to the farm, but she gets hopelessly lost. Her wound stays infected for many more months and does not heal well — Ursula still bears a deep scar that is visible to this day.

Only because she’s taken in by a group of Wolf Children does she survive. She gets to the point where she’s lost all faith in mankind when, out of the blue, a family takes her in as a milkmaid in the summer of 1947. Here she is well cared for — and here she will stay.

One night, 12-year-old Dora [Muller] climbs up onto the roof of a stationed freight train. The cars’ sliding doors are locked, and at least on the roof she’s safe from wandering animals and freeloading tramps who could do her harm. She finds a narrow depression where she makes herself as comfortable as possible and, exhausted, she falls asleep. When she awakes, the train is moving.

An icy wind blows into her face. Nevertheless, she clings to an iron bar and holds on for dear life. Her only hope is that the train will bring her to a safe place. But the journey turns into a nightmare. Dora cannot hold on much longer; she becomes nauseous and dizzy from fatigue. At the very next station, she jumps off.

She doesn’t know where she is. People are conversing in a foreign language, and she surmises that the train has taken her far into the east, to Lithuania. It’s been only a week since Dora’s mother died, and only two days since she was chased off by the cruel farm woman, in whose family Dora was just an extra mouth to feed.

Since then, she’s been living in the woods, abandoned barns, or in graveyards. One day she meets other children who, like her, wander through the forests, and through life, on their own. Together they camp at night and go begging or steal feed from troughs during the day.

When, one day by chance, Dora sees her reflection in a mirror shard that she finds in the hayloft, she’s shocked. She’s become a wild looking little thing. Her long hair hangs straggly in her face, her eyes have sunk deep into their sockets. She looks down at herself and sees how tattered her clothes have become, the holes in her torn shoes that she had stuffed with straw.

Dora breaks down and cries bitterly. ‘What have I done?’ she asks herself over and over, and blames herself for the death of her grandparents, who had raised her as a child while her mother was gone working on the farm. ‘I allowed them to starve to death, and now the dear Lord is punishing me.’

In her hysteria, she becomes a risk to the other children in the little gang. They finally walk away, leaving her behind in the farmyard. The next morning, a farmwoman finds her. The kind-hearted woman first bathes her in warm water, and then she gives her warm milk to drink and nurses her back to health. But Dora is not allowed to stay.

And so, she must make her way, once again, into the Nowhere.

This excerpt from The Wolf Children of the Eastern Front - Alone and Forgotten appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.