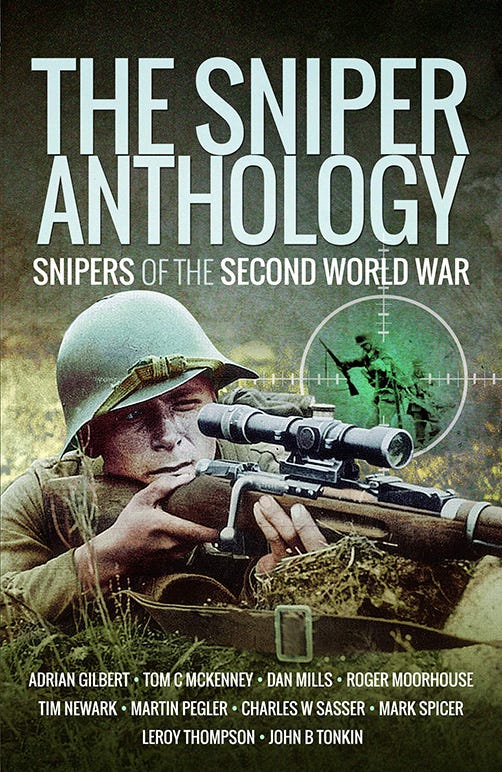

The Sniper Anthology

This week's excerpt comes from a popular title on the Snipers of the Second World War

Recently re-issued is The Sniper Anthology - Snipers of the Second World War. This is a collection of essays by noted military historians examining the role of the sniper in the war - through the lives of different individuals who made a name for themselves. The careers of top snipers from the ranks of the American, British, Finnish, German and Russian armies are featured here, each with some detail on how they became snipers and rather more on their methods of operation.

The following excerpt is from a chapter by Adrian Gilbert on Josef ‘Sepp’ Allerberger, who began his career on the Eastern Front in 1943:

February 1943 Allerberger was inducted into the Gebirgsjager - whose Austrian headquarters was in the Tyrolean town of Kufstein - before being despatched to Mittenwald to begin his basic training, which in the German Army was hard and thorough. While at Mittenwald he was assigned as a machine gunner, and it was with this speciality that he was sent with other reinforcements to join his regiment on the Eastern Front in the summer of 1943.

The 144th Mountain Regiment was part of the 3rd Mountain Division, deployed in the southern Ukraine on the west bank of the River Donets near Voroshilovgrad. Almost immediately on arrival at the front, Allerberger found himself in the thick of a Soviet offensive, launched in July 1943 and designed to force the Germans back to the River Dnieper. It was a fearsome intro duction to the war on the Eastern Front, where the outnumbered German forces were subjected to massive artillery bombardments from the Red Army, followed by wave after wave of infantry assaults that almost inevitably forced the Germans to retreat.

During the Soviet offensive it soon became obvious to Allerberger that machine gunners were a focus for Soviet fire, especially from the many Red Army sharpshooters who helped ensure that casualties among German machine-gun teams were disproportionately high. After five days of fighting, Allerberger was hit - not, in fact, by a sniper’s rifle bullet but by a shell splinter that cut into his left hand. Although this was a minor wound, he was sent to the regimental headquarters to convalesce while performing light duties.

One of his tasks was to repair damaged German weapons and to sort the piles of captured Soviet small arms. While sifting through some Soviet weapons he came across a sniper rifle, a Mosin-Nagant 91/30 with a 3.5-power PU telescopic sight. This rugged, reliable and accurate bolt-action rifle, fitted with a five-round box magazine, intrigued Allerberger; he sought and was given permission to try it out, using the copious supplies of captured Soviet ammunition for target practice.

This was essentially the same weapon that proved so deadly in the hands of both Vassili Zaitsev and Simo Hayha. Allerberger also proved a natural with the rifle, and was encouraged by the Weapons NCO to develop his shooting prowess. Soon he was capable of hitting a matchbox out to a range of 100 metres. Allerberger’s regiment took sniping seriously, and it was no coincidence that among its ranks was Matthias Hetzenauer from the Tyrol, who was to achieve an incredible score of 345 certified kills, making him Nazi Germany’s top sniper. When news of Allerberger’s skill with a rifle reached his company commander, he was released from his duties as a machine gunner and reassigned as the sniper for his company. Although a daunting prospect, this change of role provided the independently-minded Allerberger with new challenges.

During the remainder of 1943 the Germans were relentlessly pushed backwards by the Red Army, in a series of cataclysmic attacks that could not be held for long. Between the offensives, the Germans withdrew to new defensive lines, which they would hold until the next Soviet assault. These withdrawal and defensive phases gave great scope for German snipers to deliver telling blows against Soviet targets.

By mid-September the Germans had fallen back to a new defensive line in front of the Dnieper. It was clear to the Germans that the Soviets were planning to resume their offensive, if only from the number of reconnaissance patrols that were being sent out to probe German positions. Allerberger was given wide latitude by his superiors to wage his sniper war in the way he thought best. During this period he would often slip out into no man’s land during darkness, establish a good firing position and await events. On one clear morning he observed a Soviet patrol pushing forward out of a small stand of trees, entering his field of fire only 150 metres away.

Officers were a priority target for snipers, and on this morning Allerberger was in luck: leading the patrol was an extremely well-dressed officer, the smartness of his uniform giving him away. Looking through his telescopic sight, Allerberger could see the fine detail of the man’s polished leather boots as he paused to look around. It was an easy shot, aimed at the torso. As the muzzle-blast smoke disappeared, Allerberger saw the officer sink to his knees and then fall to the ground. The other Soviet soldiers initially scattered in panic, unaware of the source of the shot. Normally, Allerberger would have slipped away unobserved, but on this occasion he could see that his position was uncompromised and he quickly despatched two more enemy soldiers who were bravely but foolishly attempting to recover the body of their now dead officer.

After the war, Allerberger, Hetzenauer and another sniper from the 3rd Mountain Division, Helmut Wimsberger, were inter viewed about their sniping techniques and tactics, and all three made the point that eliminating officers could stall an enemy attack, and one even laconically noted: ‘Shot the respective leaders of enemy’s attack eight times in one day!’

This excerpt from The Sniper Anthology - Snipers of the Second World War appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.