The Long Range Desert Group in North Africa

A new book bringing together numerous photographs, documents and reminiscences from the personal collections of LRDG veterans

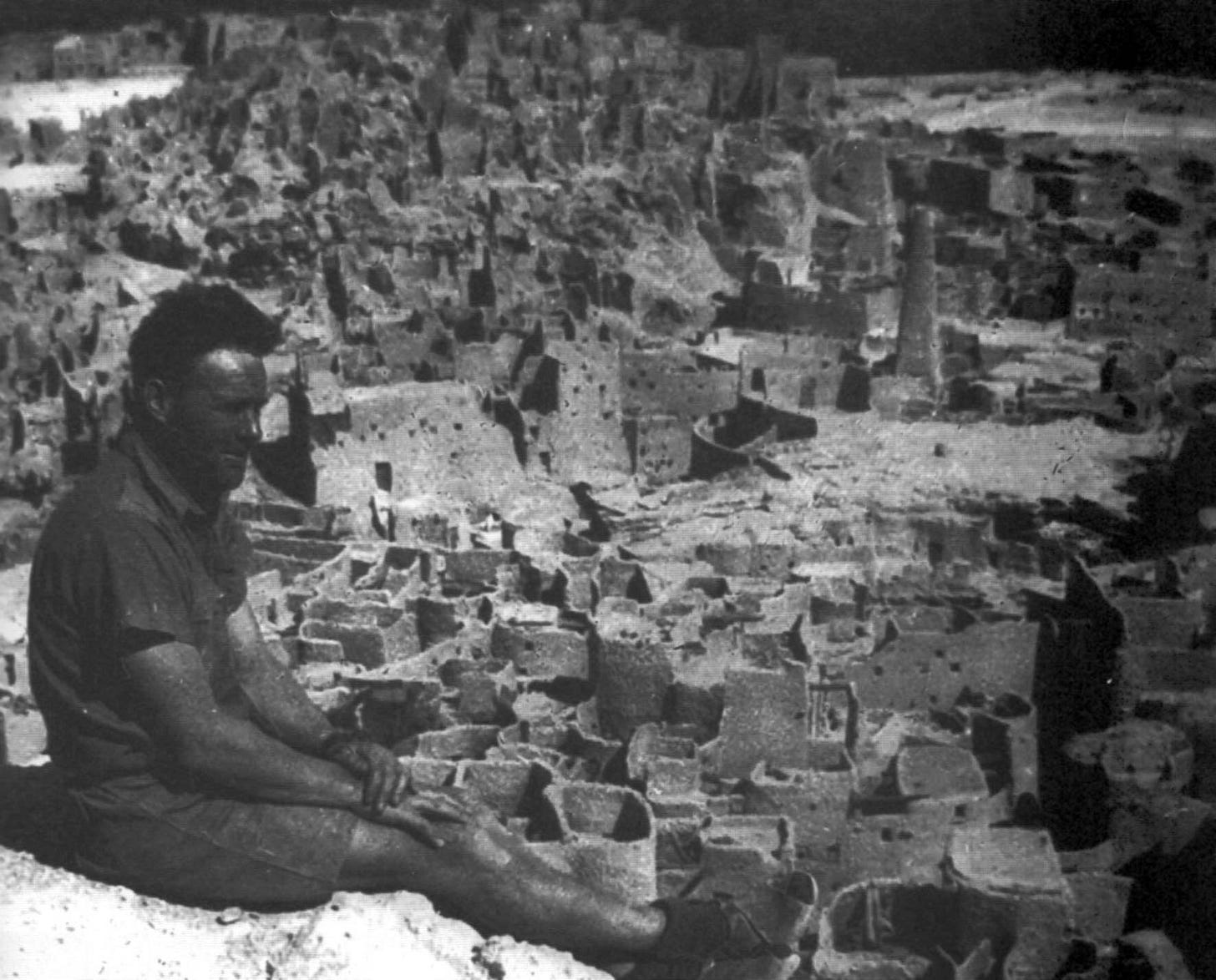

The legendary Long Range Desert Group began life as a reconnaissance and intelligence gathering unit in the desert of North Africa. Operating far behind the ‘front line’ they would soon prove themselves invaluable to the Army commanders in this role alone. Notably Montgomery was only able to launch his ‘left hook’ around the formidable Mareth Line defences in March 1943 because a deep penetration reconnaissance by the LRDG had established that there was a viable route through the difficult terrain suitable for a large force.

But the LDRG also took on offensive tasks, even before they took on the role of guiding the SAS into the desert for their opertaions.

In The Long Range Desert Group in North Africa Brendan O’Carroll has put together a splendid overview of their work. As the author of several books on the LRDG he has interviewed many former members - now he uses their personal material to provide a complete picture of how they operated. He includes many previously unpublished images of the men on patrol, their vehicles, weapons and living conditions, both on and off patrol. Absolutely indispensable to those interested in the LRDG and the origins of Britain’s Special Forces.

The following excerpt comes from early in the LRDG’s operations, in October 1940. Gunner C.O. ‘Blue’ Grimsey, a member of ‘R’ patrol, recorded the following events in his diary:

On Thursday, after a hurried breakfast of porridge and curried fish, we set out at 0630 hrs on our patrolling duties, looking for fresh track sand suitable places to lay our mines. We had little real success until just before noon whilst coasting along in 'air' formation, when our skipper in front gave the halt signal and we all stopped. Still in scattered formation, we watched him dismount and proceed to investigate two innocent - looking petrol drums and then start to dig round in the sand with his hands.

We, in our Bofors gun truck, were immediately behind Captain Steele, and soon saw him run back to his truck for his shovel which he used to excavate a box from beneath the slight mound near the drums, then another and another. Opening one, we found it neatly packed with bombs wrapped like eggs, their detonators and firing mechanisms similarly packed in separate compartments. Soon the squad had unearthed a whole dump of aerial bombs of various calibres, along with 44 gallons of aero petrol.

While a few trucks kept a lookout from a distance, the cases of bombs were all excavated and placed atop of the petrol, with detonators exposed in such a position that they could be made a target for the Vickers guns. One was mounted on the skipper's Ford, the idea being to ignite and blow up the dump with tracer fire from a safe distance.

We retreated some 800 yards. Captain Steele sent a burst of fire towards the exposed boxes. Woomph! Flame belched 400ft skyward, followed by dense black smoke. We turned tail and made for the hills.

Some of the bombs which were falling all around, filled with TNT, might explode too near to be healthy, so we took no chances. As we sped to the rocks, I watched the black smoke curling 1,000ft into the still hot air. There was another explosion and a colossal mushroom of flame seethed skyward, sending out rockets of flame.

After lunch we again struck south towards where we knew there should be a landing ground. Away in the distance could be seen dancing mirages so common at that time of day in the flat country. Huge lakes appeared and floating islands apparently suspended by invisible sky hooks gradually came down to connect with the earth as we approached.

Then there was another strange mirage, not unlike a spout of water reflecting the rays of the sun. We all gazed at this and wondered what our skipper proposed to do. As we approached, it slowly took shape as some shiny object reflecting the sun. Soon we could see it was some type of aircraft on the ground. We stopped within 1,000 yards and Captain Steele sent a burst from the Vickers gun in the direction of the plane.

There was no movement or sign of life, so we cautiously advanced. We had come across a Savoia [Savoia-Marchetti SM.79] Italian plane of the heavy bomber type, quite modern, but with a damaged undercarriage and probably awaiting repairs. Those responsible were little dreaming that enemy troops would make it necessary for them to put a guard on the machine so many hundreds of miles from enemy territory.

We fired Verey lights into the petrol tanks and the plane became a hot, molten mess. After searching the landing ground, we found four 44-gallon drums of aero petrol which we promptly fired by sending tracer shells into them. In less than an hour we had rendered useless about £15,000 worth of enemy material.

Altogether that day we reckoned we had inflicted £30,000 worth of damage to the enemy. Although it was reported shots had been fired from the hills while we were destroying the landing ground, there were no casualties.

That evening we carefully laid some of our land mines along the transport routes, the tracks of which we could plainly see in the sand. Having refilled some tins of water we found in the Italian landing ground, we set course north-west and camped for the night some 80 kilometres from the scene of operations.

On Friday 1 November while having a break after crossing some rough country, someone yelled 'Look, there's a plane!' Like lightning, we ran to our vehicles and made for the low hills covered with loose rocks which we considered would give us some protection. We got there without a hitch and no sooner had we done so than three enemy planes appeared: two heavy machines and a smaller one of the Ghibli type.

At first they circled overhead at 1,000 to 1,500ft and some of us thought we were so well concealed by our natural camouflage of the rock, but such was evidently not the case as for the second time they circled and descended to 1,000ft.

The first big plane let loose a stick of bombs which fell all around the trucks without hitting one. Captain Steele fired a burst from his Vickers gun which immediately had the desired result of making the plane climb higher. Perceiving that they intended to bomb us at a fairly high altitude and having regard for our natural camouflage, our only hope was to lie quite still away from our trucks and wait for the worst, knowing that a movement would only reveal our positions and realising that our fire would have little effect at such range.

Four times they circled, each plane dropping many small anti personnel bombs while we lay flat, still availing ourselves of such cover as the rocks would allow.

Little bits of rock and splinters came ricocheting and whining all around us and for the best part of an hour we lay there helpless as the minutes dragged by. Then another plane passed, unloading its deathly hail and another's engines grew louder as it approached to attack. At last they circled for the last time, still keeping high and headed back towards Uweinat.

One by one, we came out from behind our rocks and breathed a sigh of relief when we realised no one had been hit. By a miracle our trucks also were intact, although I am sure the enemy must have thought they had destroyed them, with such a shower of dust and smoke that the bombs had put up all around them. Apart from puncturing a few of our water tins and embedding pieces of shrapnel in our tyres, we were able to proceed, which we did at a hot pace.

This excerpt from The Long Range Desert Group in North Africa appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.