The Brookwood Memorial, situated within the Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey England, commemorates nearly 3,500 land based servicemen and women from 1939-1945 who have no known grave. The Brookwood Killers examines the cases of nineteen of these men who did not die serving their country but who were executed while servicemen - and then buried in unconsecrated ground. Paul Johnson has gathered considerable detail - in every case painting a picture of the assailant, their victim and the circumstances of the crime.

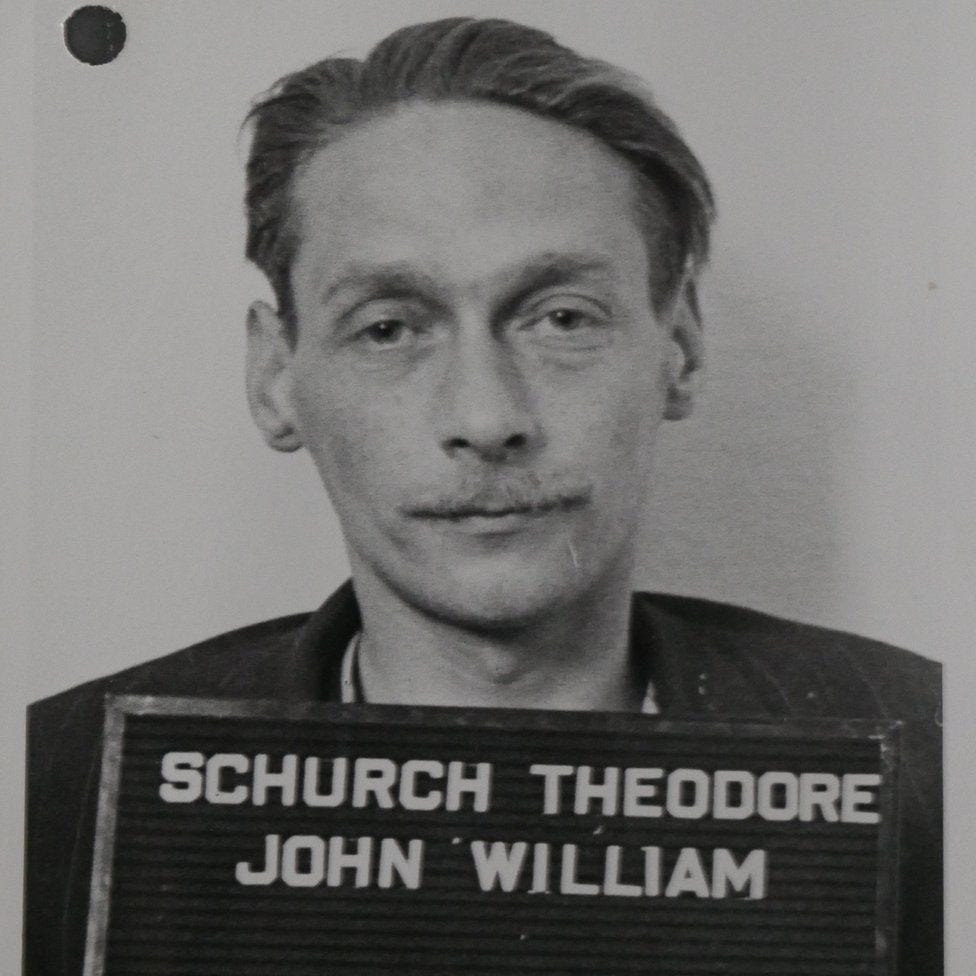

One man’s crimes stand out. Theodore Schurch was born in London, son of a Swiss national working at the Savoy Hotel. At the age of 17 Schurch was working as an accounts clerk when he became involved in the British fascist movement, which flourished in London before the war.

The following excerpt gives just a small part of the Schurch story which Johnson has reconstructed:

He always claimed that he never wore a black shirt, due to the fact his parents, who objected strenuously to the teenager’s late-night absences, were unaware of his political activities. Eventually, he was approached about becoming a member of the fascist secret service, which Schurch initially thought was a joke given his age and his limited educational achievements.

However, he was soon persuaded that intelligence gathering was simply a question of being in a position to gain information and that his scholastic abilities were of little importance. It seems that, after this, he readily agreed to undertake ‘missions’ on behalf of the party, firmly believing that his activities were accomplishing nothing more than supporting the movement in achieving its political aims, as opposed to any subversive activity.

He also claimed that, apart from senior members of the movement in his area, he had met Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of the English fascist movement, but this has never been verified.

Schurch claimed that a man named Bianchi, a member of the fascist intelligence service, suggested he would be in a good position to obtain information regarding military movements if he joined the British army. So, on Wednesday, 8 July 1936, he walked into the recruiting office in Whitehall, London, and enlisted in the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC), signing up for six years with the colours and six years with the reserves.

Initially, he was posted to Buller Barracks, Aidershot, where he spent three months learning basic soldiering, followed by an eight-week RASC driver training course at Feltham, Middlesex. During the time he was undergoing basic training he was contacted by Bianchi who arranged to meet him at Frascati’s Restaurant, Oxford Street, London, a venue celebrated for its cosmopolitanism, luxury and excellent cuisine.

This was a sumptuous and elegant setting for the instigation of international espionage, where Schurch was to be offered money for the first time. He was apparently given £5 to pay for his dress uniform, and so began his career asa paid member of the fascist intelligence service.

More details emerged about his treachery emerged at his trial, when Schurch was confronted with several witnesses who knew him when he was a Prisoner of War. During this time, acting as a 'stool pigeon' for the Italians, he pretended to be a Captain in the RASC:

Amongst these were Lieutenant John Henry Bromage, the Commanding Officer of the British submarine HMS Sahib, who had been taken prisoner by the Italians on Saturday, 24 April 1943 after being depth-charged in the Mediterranean. Bromage identified Schurch as the man he knew as Captain John Richards of the RASC, but also stated that on Monday, 3 May 1943, the treacherous soldier had asked for a private meeting with him in which he confessed who he was.

He claimed that the Italians had become aware of his German ancestry and had threatened to ‘frame’ his parents if he did not co-operate with them. Upon asking advice from Bromage about what he should do, he was told to apply for a court martial in which he could then state his case. Schurch did no such thing.

Lieutenant G.G. Hardy, RNVR, was another witness who had unwittingly helped Schurch a great deal whilst he was masquerading as Captain John Richards. They were together all day, every day, and Hardy would start arguments as to whose submarine was the best, his or Bromage’s.

It was claimed that he was gifted with an innate shrewdness and natural intelligence which compensated for his obvious lack of education.

These arguments brought forth information that Schurch required, such as the details of supply ships for the Mediterranean area. They also discussed officers of other submarines in which the German and Italian naval commands were very much interested. Schurch was able to give the Italians a complete list of‘S’ squadron submarines operating in the Mediterranean area because of his work.

The defence was headed by Lieutenant Alexander Brands KC, who stressed that Schurch had suffered a persecution complex from an early age, and it was this that caused him to be so treacherous. He was, they claimed, ‘a poor, uneducated fool who was caught young when he knew no better and jockeyed into a position from which he could not recover’.

It was clearly demonstrated that his main objective was his own personal comfort, rather than any political cause. Schurch did not call anywitnesses in his defence.

After being found guilty of all charges he received the only sentence available under the Treachery Act, death.

He appealed twice, and petitioned the King for a reprieve, but all to no end. Major Edward James Patrick Cussen of MI5 made this comment regarding Schurch’s last grasp for a reprieve, ‘This man’s history shows that he has no loyalties to anyone, and I do not feel that I am justified in suggesting that the information which he gave was of such value as to affect any recommendation which may be made to the King regarding confirmation’.

It was claimed that he was gifted with an innate shrewdness and natural intelligence which compensated for his obvious lack of education. Undoubtedly, the renumeration and the easy living were mainly responsible for his activities with the various intelligence services for whom he worked.

Theodore Schurch was hung on Friday, 4 January 1946 at Pentonville Prison by Albert Pierrepoint, assisted by Alex Riley. He was the last person to be executed in the United Kingdom for a crime other than murder, and his body was buried on the same day within the prison grounds.

He was the only British soldier to be executed for treachery during the Second World War.

This excerpt from The Brookwood Killers appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.