'The Blackout Murders'

A survey of many different crimes committed during the war looks at how some people were pushed over the edge by the Blitz

This week’s excerpt comes, unusually, from the Pen & Sword ‘True Crime’ series. Neil R. Story has written extensively about crime over the years and has published many books on the subject. The Blackout Murders: Homicide in WW2 describes a wide variety of crimes committed during the war years. Some were direct consequences of the ‘blackout’ itself, when criminals took advantage of the unusual circumstances. Others were a consequence of the destruction and trauma caused by the bombing. A few were the work of notorious men like ‘Reg’ Christie, the serial killer who served as a Wartime Reserve Police Constable, through which he gained the trust of many women. His crimes were not discovered until years after the war.

The background to these crimes tells us much about how people lived at the time and how they were affected by the war. This is especially apparent from one sad case from late 1940:

The increasing intensity of air raids began to take its toll in the war years; the combination of air raids, false alarms, blackouts, lack of sleep, shortages and rationing strained some families to the limit. Occasionally, morals fell by the wayside and for others life became cheap. There were outbursts of frustration and violence. For some it was too much, and they simply snapped.

‘It was for the best’ (Hackney, London 1940)

At the very start of the shows that may well have inspired our interest in the darker pathways of humanity, be it ‘Alfred Hitchcock Presents’, Rod Serling and ‘The Twilight Zone’, Roald Dahl’s ‘Tales of the Unexpected’ or my own personal favourite, Edward Woodward’s introductions for the precious eleven episodes of ‘In Suspicious Circumstances’, the opening monologues would often ask the viewers to consider a poignant question such as what would you have done under die circumstances presented in the programme you were about to be shown.

In that same spirit I pose two questions to ponder when reading the stories in this chapter.

Consider if it were you and your home city that were being subjected to bombing by enemy aircraft, not just for one night but night after night, and you don’t have the benefit of hindsight to know when it will end. Nights when you would hear the warning sirens and make your way to your little corrugated iron Anderson shelter down the garden. There you would sit and wait until you heard the unmistakable drone of the engines of enemy bombers, the crump of distant bombs and then explosion after explosion as they get closer, and you are left in that horrible limbo of will you be next, or will it pass over and you get to live another day? Add into that mix the day-to-day issues of life and work, love and relationships, especially if something drastically upsets that difficult balance - could you weather it all with stoicism? How much could you take before you snapped? And perhaps darker still, do you dare contemplate what you could be capable of after you snapped?

Before the days of a National Health Service, when there was far less public awareness and adoption of healthy eating habits, and more people smoked than not, many people in their sixties and seventies looked and felt old and were quite happy to see these as the twilight years of their lives. Even though there were old age pensions, many still had to work to make ends meet and often ended their years living hand to mouth just managing to ‘get by’ .

One such couple were Ida Ethel Rodway (61), who worked as a boot and shoe machinist for A & H Meltzers at their Pretoria Shoe Works in Tottenham, north London, and her husband Joseph (71) who was a retired horse-drawn delivery driver. They had been married for nearly forty years and relatives would recall that they always seemed happy and not a cross word passed between them.

On 21 September 1940, the house where they were living in rented rooms at 11 Martello Street, Hackney, was bombed. Fortunately, the couple were already in the Anderson shelter in the garden when the bomb detonated and destroyed much of their home and possessions, although they still caught some of the force of the blast. Neither suffered any serious physical injuries but Joseph was taken to Hackney Hospital in a badly distressed state. He had to leave less than a week later when the hospital required his bed for other casualties. Mrs Rodway had not been hospitalised but, as a family friend would comment, it was believed she had been receiving treatment for neurasthenia, a kinder and less stigmatised word for a condition commonly known as shell shock.

Life had not been kind to Joseph. He had been one of the last generation of men to work as drivers of horse-drawn transport, but times had moved on - steam and petrol vehicles used instead - and Joseph had not been in regular employment for ten years. He had also been losing his sight for years and became totally blind in April 1939; consequently, he was entirely reliant on Ida. She had to take more and more time off work to look after him and lost her job as a result, so they were living on Joseph’s meagre pension and dole money.

Having lost their home and nearly all their possessions, the couple had been reduced to sleeping on a floor at the home of Ida’s sister, Florence Clapp, at 39 Kingshold Road, Hackney Wick.

Joseph’s mental health had also deteriorated and he was often confused and disorientated. Ida confided in her sister that she wished the bomb that destroyed their home had killed them both. Shortly after her sister left for work at about 7.40am on 1 October 1940 Ida Rodway snapped. What happened next was written up in a statement she gave to police shortly after 11.00am the same morning:

I thought to myself, ‘What shall I do? Here am I stranded with nowhere to go. Whatever shall I do?’ I know my sister would not keep me there forever. My husband was in bed on the floor. I had been up since about seven o’clock. I was dressed. I was going to take him in a cup of tea, but I never gave him the tea. I got hold of the chopper from under the dresser in the kitchen and the carving knife. I went into the bedroom and he was sitting up in bed. I hit him on the head with the chopper. The head of the chopper fell off. He said ‘What are you doing this for?’ I said ‘I am led to desperation.’ and took hold of the knife and finished him off. I was worried to death with no one to help me.

In fact Ida Rodway had not only cleaved her husband’s skull with a hatchet, she had also cut into his throat so vigorously she had nearly detached his head from his body. She then covered his head with two pillows, cleaned herself up and went to alert the authorities. She encountered their upstairs neighbour, Lily Beauchamp, on the street, to whom she said, quite calmly and in a matter-of-fact way: ‘I have murdered my husband. I want to find a policeman. Will you get one of the wardens?’

When questioned about why she had killed her husband Mrs Rodway took pains to point out they had not quarrelled, explaining that:

‘He was my husband. I was worried about him. He was blind. We were bombed out of our home and I had nowhere to go and nobody to help me. I was worried to death. I don’t know what made me do it.’

In much the same way that thousands of beloved pets had been destroyed in September 1939, when many feared severe food shortages and the air raid regulations did not permit dogs or cats to be taken into public air raid shelters, Mrs Rodway appeared, in later police interviews, absolutely convinced she had done the kindest thing for her husband under the circumstances and that it had ‘been for the best’ . She had even taken the knife and chopper to a local knife grinder shortly before the day of the murder.

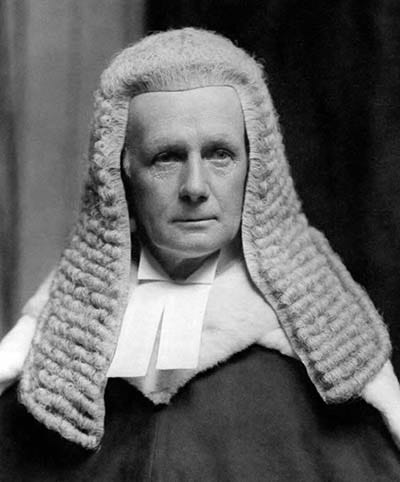

Arraigned at the Central Criminal Court on 14 November, Ida Rodway was brought before Mr Justice Wrottesley. A psychological assessment had been carried out by the medical officer of Holloway Prison who said Mrs Rodway had told him she ‘intended to plead guilty, as that would get everything settled.’ She reiterated that she believed what she had done was right and that she was ‘entirely unconcerned about the result of the trial’.

The medical officer expressed his opinion that she was unfit to plead. Mr Justice Wrottesley ordered her to be ‘detained until His Majesty’s pleasure be known’. Ida Rodway was committed to Broadmoor, where she died on 25 April 1946.

© Neil R. Story 2023, ‘The Blackout Murders: Homicide in 6th June 1944.’ Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.