The Battle of Berlin

This week's excerpt looks at the Flak towers built in the German capital

The Battle of Berlin did not begin in earnest until the end of 1943. Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, head of RAF Bomber Command, predicted that a sustained bombing campaign by both the RAF and the USAAF would bring an end to the war by itself. Harris did not achieve this - but it was not for want of trying.

The Battle of Berlin: Bomber Command Over the Third Reich, 1943–1945 brings together numerous stories of the RAF airmen involved - but also tells something of the story from the German perspective as well. Another title from the prolific Martin W. Bowman whose great strength is to bring together vivid first-person accounts from various aspects of the air war. A comprehensive account, with considerable detail on how the RAF approached the campaign and a great deal on what it meant to the men involved.

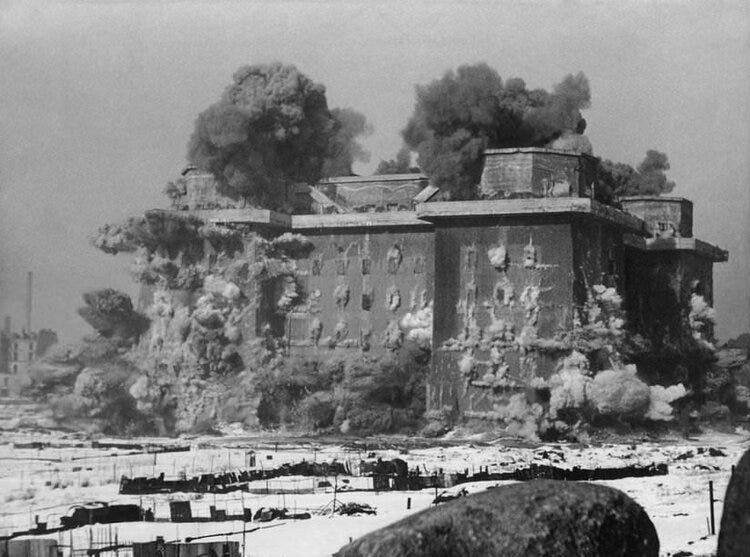

Thousands of Berliners died in the ‘battle’, but many more would have died without the extensive air defences built by the Nazis. Affronted by the first RAF raid on Berlin in 1940, Hitler had ordered the building of massive “flak towers”, which were completed in 1942:

From the outset the plan was to utilize the above-ground Hochbunker (blockhouse) bunkers as a civilian air-raid shelter with room for 10,000 civilians inside. There was also space to house the most priceless and irreplaceable holdings of fourteen museums from Berlin, while on the third floor was an eighty-five-bed hospital. The rooms were climate-controlled.

Joseph Goebbels said that they were ‘true wonders of defence’. The Fuhrer wanted six towers in Berlin but only three were built. The first of these, Flakturm I at the Bahn Zoo was in Hitler’s favoured Neo-Romantic style with some elements of medieval fortresses.

The flakturm site was flood-lit nightly despite the blackout, except during actual raids. By pouring cement around the clock, construction was completed in six months. Its location in the Tiergarten in a busy part of the city gave the tower its name and its presence would raise morale.

...

The four twin 128mm (5 inch) guns on the roof had effective range to defend against the RAF and USAAF heavy bombers. Crewed by 350 anti-aircraft personnel and assisted by the Hitler Youth, the flak towers were able to sustain a rate of fire of 8,000 rounds per minute from their multi-level guns with a range of up to 14 kilometres (8.7 miles) in a 360-degree field of fire.

From 1943 the lower platforms of the zoo facility had four twin mounts of 12.8cm Flak 40 As soon as Flakturm I was completed, contractors started on Flakturm II at Friedrichshain and Flakturm III in the Volkspark at Humboldthain on the outskirts of Berlin to create a triangle of anti-aircraft fire that covered the centre of the city

Building the towers was a serious diversion from Hitler’s primary war effort. Each day trains and barges needed to deliver 2,000 tonnes of concrete, steel and timber. Germany’s national rail timetable was adjusted to give the flak materials priority. By 1942 the five huge public shelters (Bahn Zoo; Anhalt Bahnhof close to the Potsdamer Platz-Vblkspark Humboldthain; the Turmpaar II in the Vblkspark Friedrichshain; and the Heinrich von Kleist Park) were complete, offering shelter to 65,000 people.

The lowest two floors of each tower pair were designed for up to 15,000 people, but had to cope with as many as 40,000. Crowds queued on suitcases outside during the day to get inside during night raids but the conditions became appalling with foul air, hospital corpses, vermin and concrete dust.

Armin Lehmann, a junior courier moving in and out of Hitler’s bunker, later related: ‘Men, women and children would exist for days on end, squashed side by side like sardines along every corridor and in every room. The lavatories would very quickly cease to function, clogged up by overuse and impossible to flush because of lack of running water. The passageways of the hospital units became make-do mortuaries for the dead - the nurses and doctors fearing death themselves if they dared venture out to bury the corpses. Buckets of severed limbs and other putrid body parts lined all the corridors.’

Harry Schweizer, a 17-year-old flak auxiliary with the Hitler Youth, wrote of his experiences at the Zoo Bunker which he considered the most comfortable of the three big flak towers in Berlin:

‘It was well equipped with the best available materials, whereas the interior fittings of the Friedrichshain and Humboldthain Bunkers had been skimped, only the military equipment being first rate. The Zoo Bunker’s fighting equipment consisted of four twin 128mm guns on the upper platform and a gallery about five metres lower down with a 37mm gun at each comer and a twin-barrelled 20mm gun in the centre of each side flanked by solo 20mm guns left and right.

The twin 128s were fired optically (by line of sight) whenever the weather was clear enough, otherwise electronically by remote control.

The settings came from the smaller flak bunker nearby, which only had light flak on its gallery for its defence, but was especially equipped with electronic devices. Long-range Blaupunkt radar was installed there and our firing settings came from ‘Giant Wurzburg’ radar as far away as Hanover. That bunker also contained the control room for air situation reports and was responsible for issuing air raid warnings.

‘Our training went along simultaneously with action with the heavy and light artillery pieces. We also received some basic training on radar and explosives. We suffered no casualties from air attacks, but comrades were killed by gun barrels exploding and recoils. The shells for the 128s relied on the radar readings for their fuse settings and were moved centrally on rubber rollers up to the breech. If there was only the slightest film of oil on the rollers, the already primed shell would not move fast enough into the breech and would explode....

The 128s were used mainly for firing at the leading aircraft of a group, as these were believed to be the controllers of the raid and this would cause the others to lose direction. Salvos were also fired, that is several twins firing together, when, according to the radar’s calculations, the circle of each explosion covered about fifty metres, giving the aircraft in a wide area little chance of survival.

When we were below on the gallery with the 37s or 20s driving off low-flying aircraft, we would hear the din and have to grimace to compensate for the pressure changes that came with the firing of the 128s. We were not allowed to fasten the chinstraps of our steel helmets so as to prevent injury from the blast. Later when we fired the 128s at clusters of tanks as far out as Tegel, the barrels were down to zero degrees and the shock waves were enough to break the cement of the 70cnt high and 50cm wide parapet of the gallery five metres below, exposing the steel rods beneath.

‘The 37s and 20s were seldom used against British and American aircraft as they flew above the range ofthose guns and low-flying aircraft seldom came within range. The fighting bunker had been built with an elastic foundation to take the shock of the discharge ofthe 128s. Two twin 128s firing alone would have been sufficient to break a rigid foundation.

The bunker had its own water and power supplies along with an up-to-date and well-equipped hospital in which, among others, prominent people like Hans-Ulrich Rudel, the famous Stuka pilot, could be cared for. Rudel had a 37mm cannon mounted in his aircraft, but we had later versions of the gun on the tower and he often came up to the platform to see the weapons in action during our time there. Normally only the gun crews were allowed on to the platform, but our superiors made an exception in his case.’

The smoke and shock waves produced by the large-calibre multi-level guns on the ‘G-towers’ meant the ‘Gustav’s’ aiming data had to be generated off-site using radar and detection equipment so each ‘G-tower’ had a more compact structure called the ‘L’ (Leitturm or ‘leadership’) or ‘Lower’ tower within half a kilometre, connected by underground cables.

This tower rose to roughly the height of a thirteen-storey building (40 metres), but with sides only 50 by 23 metres compared with 70 by 70 metres for the mighty gun towers. There was one cellar floor and six upper floors above that. On the roof was an observation cabin and small ‘Freya’ radars. Teenage boys of the Luftwaffenhelfer’s Oberschiiler from Zwickau in Saxony manned a ‘Wiirzburg-Riese’ (‘Giant’) which could be retracted behind a thick concrete and steel dome for protection.

All the radars were controlled from the zoo’s lower floors where a radio transmitter and headquarters control rooms carried out the central direction of the whole of Berlin’s flak and searchlight units.

On occasion Berliners could receive ample warning of a raid on their city by listening in to the broadcast on the special short wave-length used by the staff of the 1st Flak Division under Generalmajor Otto Sydow and the Flakscheinwerfergruppe Berlin under Colonel Paul Hasenfusse. Another indication was the arrival of the Hilsszug Bayern (Bavarian Relief Column), bringing food to the Hochbunker when a big raid was expected.

This excerpt from The Battle of Berlin: Bomber Command Over the Third Reich, 1943–1945 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.