In 1942 the British war cabinet was still debating the prominence - and economic resources - that should be given to Bomber warfare. This new study (2021) provides a fresh perspective on how a series of crucial decisions were made in the middle of the war. A deeply researched and highly readable study RAF at the Crossroads is a must read for anyone interested in this central plank of British - and later American - strategy for the war in Europe. Books like this should not be taken in any way as diminishing the bravery of bomber air crew - all too many of whom made the ultimate sacrifice. Nevertheless it is right to ask sceptical questions and consider the many factors in play when these decisions were made.

The following excerpt considers the context of the Bomber debate just as Bomber Command achieved one its first major ‘successes’ - the bombing of Lubeck.

With hindsight, the resurgence of the bomber strategy in 1942 might seem strange. Pre-war talk of bombers winning wars in weeks or even days now looked absurd. Bombers were killing lots of people, but there was still no evidence they could actually win wars. Following the Butt report, it required a leap of faith to imagine bombers could contribute anything to winning a war. It had always been faith rather than evidence that had sustained the bomber advocates.

It was a faith so strong it was distorting reality and defying common sense. The Air Staff had always seemed prepared to believe anything to keep their strategic bombing dream alive. Inconvenient evidence was brushed aside. Pre-war exercises had demonstrated that bombers could not be expected to hit targets by night with anything like the required accuracy, but when daylight bombing had to be abandoned it was just assumed bombing by night would work. The Blitz did not break the British people, but it was assumed the German people would crack when bombed.

When the bombing campaign was launched against oil plants in May 1940, it was claimed it would soon slow the German advance. Results were promised within weeks. Then it was months. By 1941 it was years. Despite the ever greater resources being pumped into the bomber experiment, success seemed to be receding ever further into the future. The 1941 Butt report seemed to have shattered the last remaining delusions that the bomber strategy was even remotely working. Churchill felt aggrieved that he and the country had been so seriously misled by the supposed experts.

Yet still the policy survived. Indeed, all the setbacks seemed to have surprisingly little long-term effect. The policy had not just gathered sufficient momentum to see it through these difficulties, it was actually gaining in strength. Politicians, the public and even the military were disposed to accept arguments that were at best flimsy.

The Air Ministry insisted that bombing should not be judged by what it had achieved so far, but this was simply giving the policy a blank cheque. On this basis, the bomber offensive need never achieve anything and continuing with it would still be justified. Over the years the argument that Britain had no choice has gained currency, but the choice between a method of waging war that was clearly working for the enemy and the bomber strategy always existed.

Everyone had their reasons to keep the bomber offensive going. For the Air Staff, an independent bombing strategy had always helped justify an independent air force. It was not in their interests to believe alternative strategies to bombing would work. The need to preserve RAF independence was dictating policy. Rather than analysing and questioning the general perception that bombers would decide wars, the Air Ministry sought to reinforce the perception.

The War Office saw bombing as the only way to compensate for Britain’s inferior manpower and industrial resources. Even the Admiralty could have some sympathy for a policy that, like their blockade, took years to bear fruit. Churchill needed the bomber offensive to convince Stalin that Britain was not leaving all the fighting to the Soviets. However, mere political and military expediency or departmental empire-building cannot alone explain the continuing dominance of the bomber philosophy.

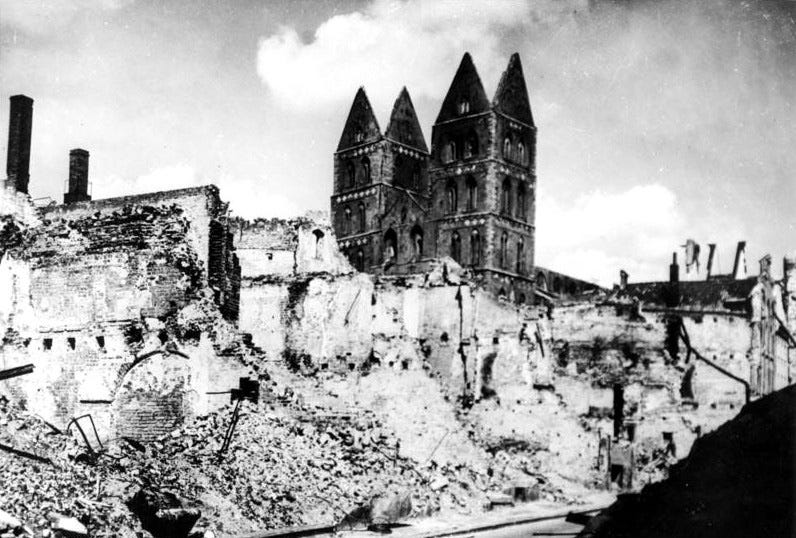

It certainly cannot explain why just one apparently successful raid on a small Baltic port should revitalise the bomber project. Lubeck was destroyed, but it did not make any difference to the fighting strength of the German armed forces on any front. It did not bring the end of the war one day nearer. It was a victory because a lot of Germans were killed and a large number of homes destroyed. That this should be seen as a victory, not just by air commanders but by the entire nation, was the culmination of decades of conditioning as to what victories in modern war comprised.

Even before the outbreak of the Great War, mighty Zeppelins ensured bomber paranoia was firmly implanted in the British psyche. In the First World War the British people had endured Zeppelins and Gothas. The raids may not have matched the lurid imagination of pre-1914 theorists but nevertheless men, women and children had been killed. After the First World War, the nation shuddered at the apocalyptic predictions of how much worse it would be in the next war.

In a democracy these fears were far more likely to be heeded by politicians and feed into government defence policy. It was a vicious circle. The terrifying talk from politicians stoked even greater fear among the public. The spectre of a country being devastated by bombing haunted politicians and public alike. The public had decades to get used to the idea that future wars would thrust civilians, men, women and children, into the firing line.

...

The British public were conditioned to believe the bomber would decide the war, just as a future generation were led to believe wars would be decided by atomic bombs. With an entire nation - military, politicians and public - all consumed by the bomber, it is perhaps not such a great surprise that, despite its problems and the clear evidence the war was being decided by other methods, the bomber strand of Britain’s military strategy survived.

Even when the strategy was failing, the few who saw the flaws in the bomber policy had to overcome three decades of presumption that this was how future wars would be fought and won. It was not a policy forced on a reluctant country by devious Air Force leaders or ruthless politicians, it was a policy that the nation readily accepted. When Lubeck was destroyed, the nation rejoiced.

This excerpt from RAF at the Crossroads, The Second Front and Strategic Bombing Debate 1942-43 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.