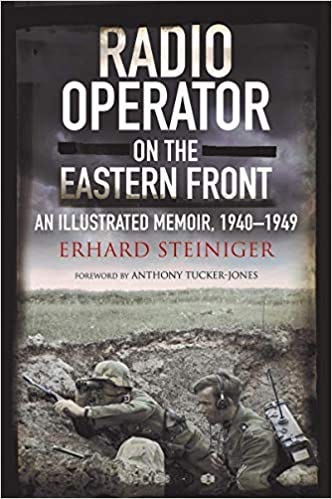

Radio Operator on the Eastern Front

A German soldier's memoir first published in English in 2020

Erhard Steiniger was born in 1920, in the German speaking part of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland, where his family had a small farm. He became a German citizen when this region became absorbed into ‘ Greater Germany’ and was conscripted in 1940. He was assigned to the Signals platoon of the 151st Regiment which as part of the 61st Infantry Division invaded the Baltic states during Barbarossa.

He marched into Lithuania with a full pack, a rifle, a 17 kilo radio and a camera. He wrote his memoirs for his family in 1981 but must clearly have been relying on some detailed notes, probably collected alongside his many photographs, even if he did not keep a full diary.

Steiniger states that he had “no great adventures, nor even really unusual experiences” but he did survive the Eastern front for four years and then more than four years as a forced labourer in Siberia ( although he says little about the latter period).

So a highly readable and seemingly honest account of the experiences of an ordinary soldier who states quite clearly that he did not want to be a hero or win any medals. Although he covers the whole war there is more detail about the early part of Barbarossa.

The following passage begins with two days, spent almost as tourists, in the Latvian capital of Riga at the beginning of July 1941:

We saw a lot of them [Latvian militia] now, formed from elements of the former Latvian Army and civilians, now restoring order in their own way in liberated Riga. We radio operators were given lodgings in the large flat of a Latvian Jew. He seemed to be ill, and spent his time in his living room in a large leather armchair. Occasionally he tried to engage us in political conversation but we saw no point in it, preferring to spend the two days of our stay in Riga getting to know the city.

Riga looked like it had once been a German city. I could imagine the enthusiasm with which my platoon commander would inspect all the historical German structures at close quarters such as the Church of St Peter, begun in 1209 and the old Guild House of the Black Heads dating from the fourteenth century.

We telegraphists of the regimental signals platoon entered a hotel en masse to be fed caviar on bread. It was the first and last time I tasted it in my life; the price for this moderate pleasure was too high. When returning to our lodgings I saw on the street victims being led off chained to shackles around their throats.

Who these people were I never found out but no German soldiers were involved. All the same, now I understood the concerns of our host, who must have feared the same fate for himself.

NB: These two images do not appear in this book. They were taken by a German official photographer.

[The 151st departed Riga on the 4 July and were soon moving into Estonia]

We had to advance. The days free of contact with the enemy came to an end. We reached the town of Fellin, which a little earlier had had to withstand a Luftwaffe air attack before our troops took it. The liqueur factory had escaped damage and remained in business. The exchange rate was one Reichsmark to ten roubles The purchases here were the first and last of their kind, for from now on the war became increasingly hard-fought.

Even at the divisional level we did not learn much about the overall situation except that the vanguard of our army corps had been disbanded. We did not have enough infantry to engage the Russian motorised units ahead.

The Estonians with their blue-black-white flags welcomed us as liberators as the Latvians had done previously. Estonian volunteers were assembled into auxiliary corps under the superintendence of a German officer but led by an Estonian commander. They were given special tasks which required native speakers, such as the neutralisation of Russian stragglers operating from ambush positions.

The topography of Estonia is hilly and more rugged than Latvia and for that reason more handsome. To the north we found it increasingly interspersed with giant boulders deposited there in the Ice Ages and therefore debris from Scandinavia. Personally I preferred Estonia to Latvia. The Estonian coast from the Gulf of Finland to the Bay of Riga, which I got to know better later in the war, reinforced the positive impression I had of this country.

Around 11 or 12 July we reached Pilistvere. Hauptmann Michalik and his horsemen (of the regimental mounted platoon) were sent to cleanse some fields of wheat from which we had received fire. It was here that the next line of Russian defence awaited us, this side of Poltsamaa.

I can still see in my mind’s eye the white-painted Pilistvere church where we put our signals vehicles under cover, for the Russian artillery had the entire area of our regiment’s advance in sight and range. It was our first experience of artillery fire concentrated in such a manner.

In the area around Pilistvere we came to a place on the road of our advance at which three trucks of the advance party had been ambushed. We found the massacred crews in the ditch under the trees to the left of the road - eyes gouged out, sex organs cut off. The corpses were already decomposing. Worms had already moved into the eye sockets and the flesh of the eyebrows. Steel helmets and equipment lay scattered around. The message from the Russians was that they took no prisoners.

This included men found wounded who were killed off as unnecessary ballast for the Red Army. The Soviets were not signatories to the Geneva Convention. This fact came home to us here for the first time, Army Ambulances, recognisable from afar by the large red cross on a white background, seemed to be priority targets.

Now we understood the merciless cruelty of this war. As a result of what we saw here, the conviction spread amongst us all )that it was now victory or death. Our fate as soldiers at the front was less important than sparing the people at home such cruelty.

In any case a certain black humour now replaced our fear of death to some extent. As for the atrocities which certain German special units committed in the Polish and Russian areas, essentially we knew nothing of them.

... the second great milestone for me in the Russian campaign was Poltsamaa where I learned to smoke. Heinz Schimanski and I were ordered to 1st Battalion and on the way to the battalion command post had been forced frequently to leave the highway and seek shelter, the heavy Russian artillery maintaining almost continuous fire on our supply road.

In the intervals between each barrage, a few of their 7.62-cm flattrajectory ‘Ratch-Boom’ cannons kept up nuisance fire. This was a feared weapon for us because there was absolutely no possibility of reacting to it. The shell arrived and exploded before the sound was heard of the gun discharging. The Russians even used it to fire at a single man.

The Tross [baggage and support] and fighting vehicles strung out across the terrain, and the men of 13th and 14th Companies, all suffered casualties. Gefreiter Heinze of 14th Company, the hero who destroyed ten enemy tanks in twenty minutes at Piezai, fell here. A soldier’s fate!

Seizing an opportunity, we had reported to 1st Battalion and then dug a slit trench very quickly, covering it with slivers of tree trunk, brushwood and sods of turf to protect against splinters. At our feet in the trench lay our radio equipment with only the aerial protruding. Hidden thus below ground we felt safer than having to listen to Russian shells whizzing past immediately above our trench.

Apparently they suspected that the battalion command post was at the edge of the woods, instead it was about thirty metres beyond in a field of rye. Nevertheless, the concert of shells hissing and bursting tore at the nerves, and then followed the evil spray of sharp shell splinters swirling out from the axis of the explosion to end up in the field or tree trunks. The black smoke would clear - and if one did not hear the cry ‘Sanitater!’ (‘Medic’) one could be content, though often those hit were no longer able to call out.

The first casualty in our immediate vicinity was the provisions cart. It had been driven up the field path along the edge of the wood, and now its dead horses lay near our slit trench. The heat bloated their bodies and a stinking broth welled up from their wounds. Who could ever forget this stink of carcass, which one came across constantly in these weeks of the advance!

Heinz and I left our slit trench only for the most urgent reasons. Our toilet was a shell crater behind the rotting horses. We had to monitor the telephone connection and if this were interrupted then we would superimpose telegraphy so as to guarantee that the battalion was never cut off from the regiment, and that was our job.

One day Heinz offered me his pack of cigarettes with the invitation, ‘Go on, take it, it will calm you down.’ It was at a time when our sector was being bombarded by the Russian artillery. Over those ten days I became a chain smoker. The cigarette butts which we extinguished in the earth surrounding our slit trench formed a kind of mosaic, the evidence of a nerve-racked impotence...

Those days outside Poltsamaa caused our troops appreciable losses. I remember the shipping out of a seriously wounded man with blood-soaked bandages, who from the stretcher raised his head slightly, his face waxen and distorted with pain, to cry out, ‘Herr Hauptmann, destroy the Russians - and on to Moscow!’ Then his strength gave out and his head sank back.

Our regimental signals platoon also suffered its first losses. Feldwebel Kiausch lost a leg in the churchyard at Pilistvere. At 3rd Battalion a shell exploded on the edge of a slit trench in which three men of the construction troop had sought cover. Horst Salomon, an enthusiastic handball player with the Danzig sporting association, was dead. Shell splinters cut open his body in strips from the legs upward. His two companions, Alois Weiss and Max Herrmann, were seriously wounded. We felt certain they would not be the last.

In the Polish and French campaigns our signals platoon had suffered no casualties, even though our regiment had been involved in heavy fighting at Mlava, Pultusk and Praga in Poland, at the storming of Fort Eben Emael in Belgium and at Dunkirk.

After ten days Poltsamaa fell to us almost without a fight. Unteroffizier Presch and Hans Weikert relieved us, and we returned to the regimental command post. We shaved off our beards and washed the filth from our bodies and clothing in a stream.

From Radio Operator on the Eastern Front: An Illustrated Memoir, 1940-1949

This excerpt appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author.