'Pioneers of Irregular Warfare'

The early British military thinking about Special Forces to support 'partisans'

With the invasion of France in 1940 the greater part of Europe fell under Nazi occupation. As the British military establishment faced up to the need to defend the country from an invasion, thoughts were also turning to how to ultimately defeat the Nazis. The prospect of a conventional military force to confront the Germans seemed very far off, especially while Britain stood alone.

Major General Sir John Kennedy briefed the Chiefs of Staff in June 1940:

We are certainly not going to win the war by offensives in mass and the only way of success is by undermining Germany internally and by action in the occupied territories. German aggression has in fact presented us with an opportunity never before equalled in history for bringing down a great aggressive power by irregular operations, propaganda and subversion enlarging into rebel activities ... It must be recognised as a principal that not only are these activities part of the grand strategy of the war, [but] probably the only hope of winning the war.

However there was little practical thinking about how this would actually be achieved. The job fell to MI (R) a secretive section of Military Intelligence that sat alongside the now rather better known MI5 and MI6.

Pioneers of Irregular Warfare: Secrets of the Military Intelligence Research Department of the Second World War is a deeply researched study of how the business of irregular warfare got underway and a survey of the operations subsequently undertaken. It provides summaries of these operations and has a multitude of references - but this is not the book for those who want first hand accounts of the action.It is an excellent primer for those who want to read further.

Lt Colonel JCF Holland, head of MI(R), and Brigadier Colin Gubbins, later head of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) are two key figures in the story. The following two passages illustrate the books approach:

“Holland believed the key to supporting national resistance movements would be the creation of specialist military units who could operate behind enemy lines.

It was a principle at the heart of the creation of the Commandos, LRDG, SAS, Jedburgh teams and Chindits...

On 7 June 1940 Holland produced ‘An Appreciation of the Capabilities and Composition of a small force operating behind the enemy lines in the offensive’. The object of this force would be ‘to disrupt enemy L of C [Lines of Communication], destroy dumps and disorganise HQ’, its methods being to travel fast,... remain concealed ... avoid organised opposition as much as practicable ... attack the weak points in the enemy’s organisation, make the sites untenable as long as possible and then, in most cases, depart’.

This farsighted document became a blueprint for special forces, including the SAS. Such units, working with the local resistance, would operate in conjunction with the regular forces simultaneously attacking the enemy front. The troops would be infiltrated piecemeal or delivered by parachute drop, by sea or by raids through sparsely populated areas, with the principal targets being railways, roads, supply dumps and headquarters. The force would travel light and be supplied by air.

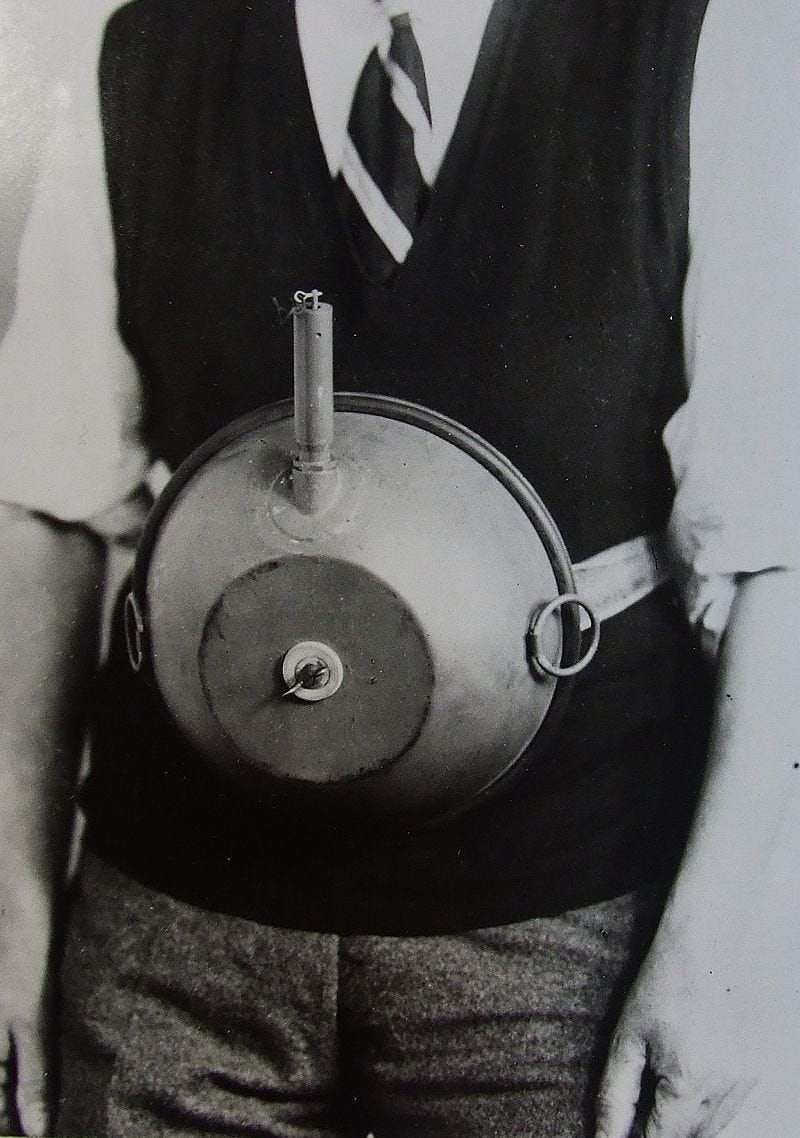

Additional firepower would come from coordinated air attacks rather than having to provide their own heavy artillery. Operations would depend on effective portable wireless communications, although in 1940 the limit of imagination was for a set transported in a ‘perambulator’.

This vision was perhaps the most enduring legacy of Jo Holland’s MI(R).

In May 1939 Gubbins had produced a secret pamphlet ‘The Partisan Leader's Handbook’ that was to become a foundational guide for the SOE training programme. The British were able to draw on their own experiences as ‘the occupying force’ in Ireland and Palestine - and reflect on how they had dealt with ‘partisans’ operating against them.

“With memories of the British Army’s experience in Ireland, the importance of using a friendly population to gather intelligence was stressed.

The 1921 Notes on Guerrilla Warfare in Ireland had observed that ‘the leakage of information in Ireland is very great, and it may be generally accepted that no inhabitant or civilian employee is to be trusted ‘.

The Partisan Leader's Handbook therefore stressed that partisans should work hard not to aggravate the people, but instead foster their hatred of the enemy and their sense of resistance. This might be either by providing information to the guerrillas or at least by withholding it from the enemy.

But, from experience in Ireland, Gubbins also warned that informers posed the gravest risk to the guerrillas:

‘The most stringent and ruthless measures must at all times be used against informers; immediately on proof of guilt they must be killed, and, if possible, a note pinned on the body stating that the man was an informer.’

The style was borrowed from Scheme D of March 1939 which included advice on the assassination of members of the Gestapo ‘in order to produce in the minds of the local inhabitants that the guerrillas were more to be feared than the occupying secret police. In this way, (a technique which was learnt from the Irish in 1920) the business of collection of intelligence would become more and more difficult for the enemy.’

Based on British policy in Ireland and Palestine, Gubbins warned of a likely campaign of ‘Searches, raids ... curfew, passport and other regulations’ against the partisans, which would eventually force them to ‘go on the run’, surviving ‘as a band in some suitable areas where the nature of the country enables them to be relatively secure’.

A deliberate omission was the effects on a partisan movement of reprisals against the civilian population. According to Gubbins, this was considered ‘as a point best passed by in silence’.

These excerpts appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author.