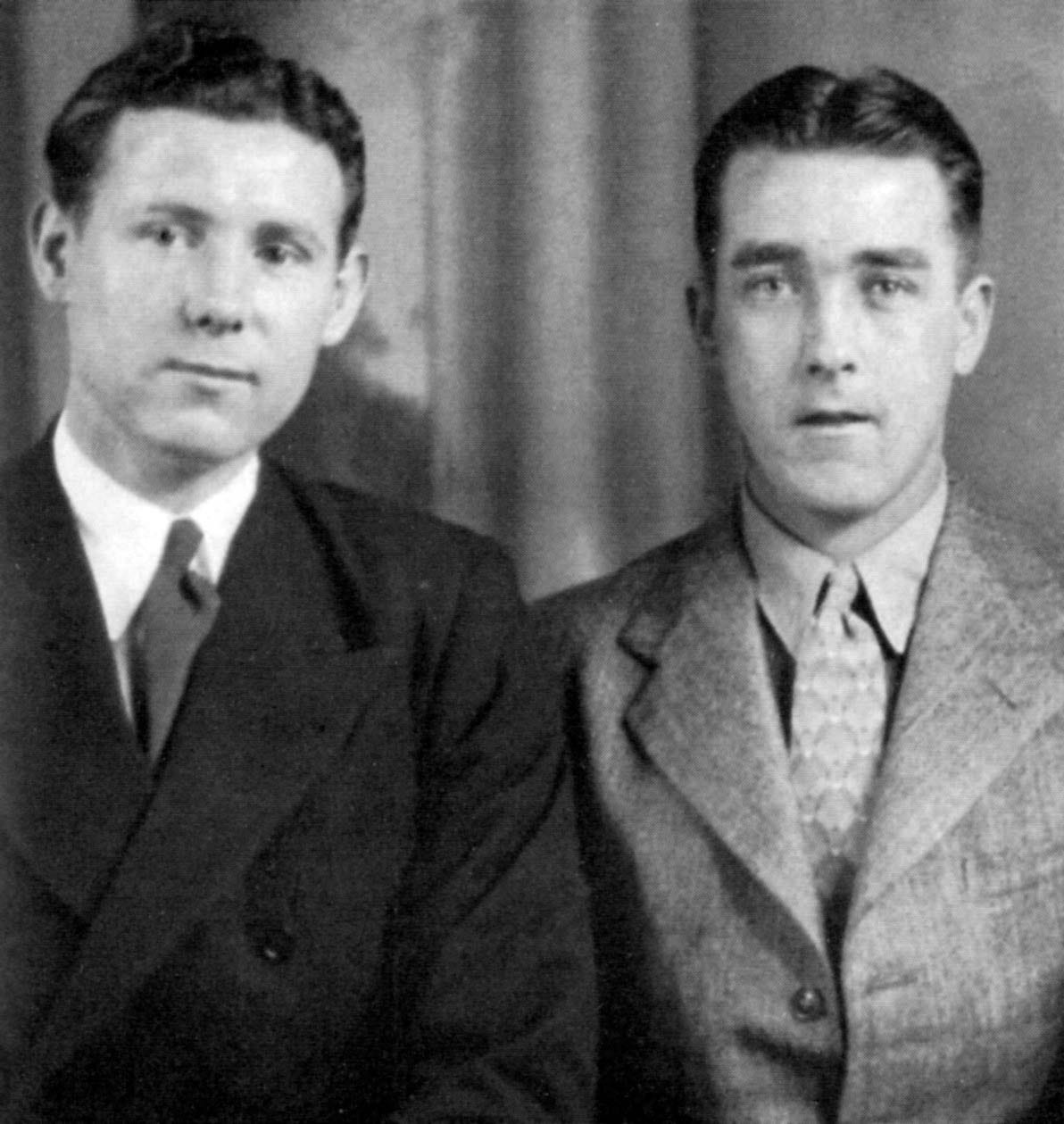

In Singapore thousands of servicemen were coming to terms with becoming Prisoners of War of the Japanese. They faced a terrible ordeal that many would not survive. At first almost all were imprisoned in Changi in Singapore - but over time many would would shipped out to various work camps in the territories occupied by the Japanese. John McEwan was only just 21 when he became a POW in February 1942. He had volunteered at the outbreak of war and had only left Britain in the summer of 1941.

Many years later he wrote a memoir, Out of the Depths of Hell, that was remarkably free of bitterness - yet unsparing in the details of what they all endured.

The following excerpt deals with the period in the months after their capture in 1942, some time before he was transferred to the notorious copper mine at Kinkaseki:

That was the way the Japs worked. No warning was given. They appeared from out of the blue, took whatever men they wanted and off they would go to pastures new. The move was preceded by an announcement to those concerned that they were to be moved to a ‘new campo’ where they would do light work and have better food.

This was the carrot dangled in front of the unwary prisoners. They would be jubilant at the prospect of leaving dreadful Changi behind because ‘the grass is always greener...’ (or so they say). We were all to discover, to our dismay, that it was a worthless carrot. We were certain then that nothing could be worse than Changi and the continual hunger and monotony of the place.

I was glad when a party of Japanese officers and guards arrived at the camp and I was included in a work party of about two-hundred or so. Within half an hour we were hustled aboard army trucks, with surly looking Jap guards with rifles at the ready. We were taken to Singapore City where we were billeted at ‘The Great World’, a former pleasure arena, with the bare ground to sleep on.

We were to be there about two months in the company of the mean- minded guards, who lost no opportunity for letting us know who was master and who was slave. Their fists, boots and rifle butts were to the fore in this operation. It made me almost wish for dear old Changi!

Each day after being paraded and split into work parties, we marched to our place of toil and shock-waves surged through us as we saw further examples of the barbarity of the Japanese. Along the route long bamboo poles had been placed and, swaying gruesomely in the wind, were the severed heads of Chinese men. They had been decapitated by their brutal conquerors and were shown for the attention of all. I shuddered and resolved to watch my step lest I keep company with these poor, savaged civilians.

I had left home as a country-boy, innocent ofthe ways ofthe big, wide world. I was fast accumulating a wealth of experience of good and evil and of the incredible bestiality of man. King George’s twelve pence had bought for me the level ofexperience that had come to the greatest explorers and travellers in history. I had no straw sticking from my ears now.

I had travelled the world, or a considerable part of it. I had seen the good and bad of Capetown, the terrible grinding poverty of India and its system of Caste. I had had my own catastrophic involvement in the bloody battles in Malaya and the disaster of Singapore but here and now, right before my astonished eyes, was the proof of the cold, pitiless brutality of which man is capable towards his fellow man, those repulsive, bloodstained heads on slender lengths of bamboo, nodding sightless eyes towards me in the gentle wind.

As for me, a prisoner, I had to stumble on through the winding roads of the rest of my life.

There were occasional rays of light in the darkness which lighted our dreary lives during those early days. We shared a road squad with some Australians. Australians are often rough and ready, often uncouth - my kind of people. They are typically good-hearted and good muckers in time of trouble and strife. They also have a ready, earthy wit.

A young Aussie had been placed in charge of the road roller. He received three gallons of petrol per day while the Jap overseer appeared unaware that the roller was fuelled with coal or wood. Some daring natives received petrol bargains while our squad received food and cigarettes in exchange.

Another task had us unloading a battered old tramp steamer at the docks and storing the cargo in a nearby godown (warehouse). As we sweated in and out of the rat-infested holds we came across a crate, identified by its label as EX-LAX. This was, of course, a chocolate-coated purgative popular with the Western world’s constipated citizens.

The Japanese guards were ever on the search for plunder and one sentry enquired what the label said. John Dempsey Kane was equal to that challenge. He informed the guard, with much signing, ‘yum-yumming’, and rubbing of his stomach that it was chocolate and further that it was ‘Joto - taksan joto’ (good — very good). The rest of the squad were enjoying JDK’s deception, in a furtive manner, and it appeared that the Jap sentry did so too. He burst the crate open with his bayonet, stuffed his pockets with the goodies and closed and sealed it tightly again ensuring that the POWS would be unable to share in the spoils.

With diarrhoea our constant companion, these days, it was the very last thing we needed. Like ‘Little Audrey’ we laughed and laughed and laughed at the thought of having attacked the enemy from the rear!

We continued with the unloading but kept an eye on the guard who was now sharing his ‘chocolate’ with his mates. It was difficult not to show our amusement as they pulled little squares of chocolate ‘shit shatterers’ (as we called them) from their pockets and stuffed them into their mouths. We hoped to be well away when the Jap realized that he had been caught ‘with his trousers down,’ so to speak. Meanwhile, and before the laxative began to have its effect, they licked their lips with obvious satisfaction at the delicate flavour.

This excerpt from Out of the Depths of Hell appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.